Slobodan Dan Paich Comparative Culture Papers

Presented in June 2007 at the Scenography International Prague Quadrenniale Research Conference on Transliteracy—The History and Theory of Scenography: interdisciplinary making and reading of images in entertainment environments.

Scenography and Genius Loci

Re-investing Public Space with Mytho-Sculptural Elements for Performance

by Slobodan Dan Paich

Presented at the Scenography International Prague Quadrenniale Research Conference on Transliteracy–The History and Theory of Scenography: interdisciplinary making and reading of images in entertainment environments

Abstract

The traditional concept of genius loci, spirit of place, has a number of meanings ranging from the special atmosphere of a place, through human cultural responses to a place, to notions of the guardian spirit of a place. In the theater, this expresses itself in thousands of ways, from Giselle appearing in the forest clearing to Beckett's characters buried in the sand. This paper for the 2007 Scenography International Conference in Prague will explore the category of investing existing non-theater space with scenographic incidents for a performance, or, more specifically, articulating possible sub-categories of site-specific work that focuses on reinvesting the space with new meaning for the sake of a performance, utilizing scenographic elements.

Additionally, this paper will discuss some theoretical, dramaturgical, and visual issues raised by the presence of scenography in public place, with the intention of furthering dialogue between scholars and practitioners in this emerging field. The paper's conclusions will be more in the form of open questions rather than proofs of any particular thesis.

For reasons of theoretical exploration, not as ends in themselves, the samples will come from the author's current and past body of work, drawing from lifelong practice and experimentation in staging scenographic elements in public place for theater performance. The examples used will be with the intention of eliciting thinking on typology and the theoretical and practical implications of creating a theater setting without a theater building.

Introduction: Place-Marking, Place-Making

The provocation for creating this paper is a search for connections between territory marking, place-making, and performance spaces. The series of open questions throughout the paper introduce the issues without presenting them as rhetoric or conclusions. Here we start with a first set:

- Is place-marking perhaps an extension of tool making, husbandry, and crop development?

- Does the awareness of a spirit of a place, genius loci, begin with marking territory?

- Is territorial instinct common to all biological beings?

- What characteristics are unique to human claims of territory?

- Is the creation of communal, gathering, ceremonial, and symbolic space a function or result of territorial claims?

Just as tool making, shared only with a small number of other animals, distinguished humans as unique species, so does place-making. A large number of archeological findings reveal the very early creation of communal, shared, and characteristically symbolic places.

In this paper we shall explore some scenic manifestations and instances of place-making from the history of culture. As stated in the abstract, we will look at a specific contemporary performance practice for the sake of appreciating and understanding the presence of scenographic elements in public space.

Image 1. Grating of a Street Shrine in Venice, Italy.

In Venice there is a street shrine (image 1). Every day someone places a fresh flower onto the grating of the shrine. The simple protective wrought iron covering incorporates the emblem of Stella Maris, Madonna of the Sea, the patron saint of seafarers.

Image 2. Commemorative Plaque for a Dead Solder, Northern Italy.

The second example (image 2) is a place-marker in the shape of traditional ancient Roman inscriptions: a twentieth century commemorative plaque for a dead solder in northern Italy.

Image 3. A reconstruction of an osilum positioning. The original is in Museo Nazionale in Naples. Reconstruction and photograph by S.D. Paich.

The third example (image 3) is an osilum, a votive object placed in trees by ancient Romans to invest or mark a place with a special meaning. This image is of a reconstruction of osilum positioning. Another osilum, Pan Leading Bacchantes (image 4) is an osilum from Pompeii, a good example of one of these ancient objects. The hole for hanging it in a tree is clearly visible above the three women.

Image 4. Osilum from Pompeii depicting Pan leading Bacchantes.

Invested Place–Creating a Scene

The concept of the genius loci was prevalent in the language of garden design, documented in the seventeenth to nineteenth century. The celebration and understanding of the power and uniqueness of certain places was as old as humanity. To clarify and share the concept of the-spirit-of-a-place we shall give some well-known examples:

- Stonehenge, a prehistoric stone circle in Britain, is famous for its alignment to the rising sun at summer solstice and was likely a place of worship for more than 3,000 years.

- Delphi, in ancient Greece, was an oracle center that held an archaic carved stone”the omphalos”naval of the world. It appears to have been a ceremonial ground prior to becoming the center of the cult of Apollo.

- The ancient Egyptian pyramids, held clearly in the cultural memory and awareness of the world today, have an impeccable alignment to the four cardinal points. This alignment determined their placement.

- Lesser known but excellent examples of places invested with significance are the ancient Egyptian temples such as Edfu, dedicated to the ruler of the people: Pharaoh, as an incarnation of Horus.

- Another example from Egypt is the temple complex at Dendera, celebrated in the ancient world for its connection to Osiris.

Some of those temples are built around calendar events, and their scenic elements capture rays of the sun and most importantly the reappearance and helical rising of the star Sirius, which determined the Egyptian calendar. In this paper, we are responding to these calendar events and their relationship to Egyptian temples by looking at a series of ambulatory rituals and their scenic elements. We shall explore that further in the section devoted to the root metaphor of theater.

Historically closer in time to us we can find many significant examples of scenographic elements as place-markers in the symbolic garden structures of Europe. As we said earlier, the genius loci was a concept prevalent in the language of garden design during the Renaissance, Baroque, post-Baroque, as well as Classicistic and Romantic eras. Both Stowe and Rausham in England”and many Italian gardens such as Villa D'Este at Tivoli or Villa Aldobrandiny in Alban hills outside Rome”used the notion of the genius loci in their creation.

Marking a place–Permanently or Temporarily

The other strong motivation for this paper, which underlies all of the examples selected, is an attempt to read images of performance and ritual in the broadest intercultural sense.

The paper explores scene making as part of a greater pattern of cultural continuity that expresses itself above and beyond the instinct for survival. This subtle quality we will touch upon in the final section.

Image 5. Detail of painting Madonna with Saints by Piero della Francesca, c.1470

In the spirit of broad intercultural reading, the next six examples sited have characteristics of both place-markers and imagination triggers, carriers of elusive nonverbal communication so typical of scenographic art. They are images that work directly on audience's inner imaginative function. Two of them exist in theater-like space typical of Renaissance painting and engraving. First, a detail of the painting Madonna with Saints by Piero della Francesca (image 5), shows an egg suspended on a golden chain in a similar and evocative way that osilums were hung in the trees and porticos of the ancient world.

Image 6. Alchemist's Egg. Detail. [Maier: 1969, p.384]

The second example that evokes a theater-like space is the alchemist's egg (image 6), in a detail from an alchemical emblem from Michael Maier's Atalanta Fugiens. Alchemical emblems such as these were designed to affect the elusive inner imaginative function of the reader. Each emblem in the book had a musical composition specially created for it, so the visual reading of images was aided by words and music. Each emblem was also a scene composed with carefully chosen mythological and fantastical images. The images were intended to work regardless if the reader knew all the mythological references or not, and also addressed a direct communication through images familiar to the audience without reading and writing skills. In both examples, the egg is an imagination trigger, employed for its instinctual atavistic quality that may evoke a visceral connection to origins.

Image 7. Omphalos, the naval of the world, at Delphi. Representation of the more ancient place-marker kept in the inner sanctuary of the Temple of Apollo.

The ancients knew about the scenic power of well placed objects. A great example of that is image 7, representing the omphalos, the naval of the world, at Delphi. The one in the illustration is a representation of the more ancient place-marker kept in the inner sanctuary of the Temple of Apollo, revered as tomb of Dionysius in pre-recorded times. That archaic stone carving was the central scenic element at Delphi, and marked and determined the nature of the place.

Image 8. Co-existence, an Artship Ensemble performance in Lafayette Park, San Francisco, 2005.

To introduce the reading-of-images from contemporary performance practice, the following integrates some of the ideas touched upon in the examples above. Co-existence, performed by the Artship Ensemble in San Francisco's Lafayette Park, centered around fifty egg-matrix scenic sculptures of different sizes that were placed in and around trees on the half-acre performance site (image 8).

As stated before, the ancients understood the power of well placed objects. It could be restated that communication through imagery has been highly developed and refined throughout history and across civilizations.

The aliveness-of-imagination and reading-of-imagery were an important part of cultures where only small number of people could read and write. As we speculated earlier, the power of aliveness-of-imagery and the placement of symbols was discovered early in the development of cultures.

It is often difficult to separate the organic and instinctual need of people to gather under a symbol from intentional propaganda.

The two well-known examples of this are the Kaaba (Ka’ba) at Mecca and the cave at Lourdes.

The cave at Lourdes was launched when a fourteen year old girl, Bernadette Soubirous, saw visions of the Virgin Mary there in 1858. The result of this visitation was a discovery of a healing spring in the cave that has attracted believers ever since, many in wheelchairs or on stretchers. These pilgrims crowd the cave for a taste of the water from the spring with hopes for a miracle.

The Kaaba, on the other hand, is the center of the Islamic world, and every pious act—particularly prayer—is directed toward it.

The structure predates Islam. It is believed to have been first built by the prophet Abraham and his son Ishmael, although there are no archaeological findings to support this argument. It is known, however, that the pre-Islamic Kaaba was rebuilt several times by the tribes ruling Mecca. The pilgrimage to Mecca”the Hajj”is one of the Five Pillars of Islam. It should be attempted at least once in the lifetime of all able-bodied Muslims who can afford to do so. In this process the Kaaba is used as a devotional focal point—a place-holder—which is a scenic signifier for religious recollection.

In ancient Greece, crowds of pilgrims made their way to the Delphic oracle at the Temple of Apollo or the oracle of Zeus at Dodona. And once every four years, during the Olympic games, the temple of Zeus at Olympia was the destination of worshipers from every part of the Hellenic world.

For our purpose of exploring aliveness-of-imagination and reading-of-imagery in the ancient Greek world we will look at fertility festivals, such as the Eleusinian Mysteries celebrating Demeter and Core-Persephone, as celebrations for the return of the nourishing seasons. Also, festivals dedicated to Dionysus attracted large numbers of pilgrims. There, fertility rites were celebrated as containers for experiences outside everyday life, nurturing the need for symbolic function, which may have evolved into the emergence of theater practice.

Image 9. Ears of Wheat, 11.5 inches high. Made of gold. Found at Syracuse, c. 4-3rd century B.C.

The example in image 9, the gold ceremonial Ears of Wheat was probably part of a rite of Demeter and Core enacted at Eleusis and a number of other places in the Greek world. It was a potent, focusing scenic instrument that united the participants–much like the image of the alchemist's egg brought out of its context and stood on end, or the hanging egg in Piero della Francesca's painting. The Ear of Wheat is an imagination trigger–it appears almost real, and yet is stylized by being crafted in gold. The audience, recognizing that it was an artifice, was united by an inward recollection–an evocation of the real thing. And in that way it connected them, fulfilling the ritual purpose of the moment. This example carries the great theater paradox: that representation sometimes evokes the deeper connection to the represented then the raw object itself.

Image 10. Detail of a Guardian Sculpture at Isola Bella, an island palace on Lago Maggiore, near Stresa, Northern Italy.

The example (image 10) leads us to the more specific place-marking and phenomena related to the spirit of the place and its expressions, inventions, and physicality. It also points to antecedents, traditional links, and furthers our attempts at articulating notions of investing existing non-theater space with a scenographic incident.

The example is a detail of a guardian sculpture at the late Renaissance/Baroque theater in the gardens of Isola Bella, the island palace on Lake Maggiore, near Stresa, Northern Italy.

A garden as a permanent theater setting where a walk acts as an ordering element will play a part in this exploration of scenographic elements in the landscape.

John Dixon Hunt in his Garden and Grove—The Italian Renaissance Garden in the English Imagination 1600-1750 talks about the influence of the Roman poet Ovid's opus Metamorphosis on garden design in the Renaissance. The botanical allegories and transformational resolution of the majority of the myth he describes has inspired programmatic starting points for garden designers. Inclusion of Mytho-sculptoral elements in the garden invested the place with implied meaning and made them into a particular scene. John Dixon Hunt writes:

Equally, features of the physical landscape are explained in terms of its presiding deities, whose stories are often told to validate some particular numen of a territory...[Hunt:1986, p.42]

In the same chapter, entitled “Ovid in the Garden,” he continues:/p>

One particular example of a garden's deliberate invocation of the Latin poem as at the Villa D'Este. Here in 1645 John Evelyn found “a long and spacious walk, full of fountains, under which is historiz'd the whole Ovidian Metamorphosis in mezzo relievo rearly Sculptur'd.” These terracotta plaques along the Walk of the Hundred Fountains are illustrated in various contemporary engravings, although without any precision of subject. Today these plaques are obliterated with moth and maidenfern. [Hunt:1986, p.43]

The ambiguous relationship between naturally-created and art-made is explored by Hunt in the same chapter when he analyzes Ovid's linguistic painting of scenery for his poems:

…that there ‘was an ancient forest which no axe had ever touched, and in the heart of it a cave, overgrown with branches and osiers, forming a low arch with it rocky walls, rich in bubbling springs.’ That forming (Latin efficiens) ascribes to nature the same properties as those derived from an architect; such effects were readily achieved in gardens, too. A little later in the third book Ovid explicitly claims an artistry for nature (his own poetry, of course, being analogous to that art its presentation of scenery). [Hunt:1986, p.43]

Further in the text, Hunt writes:

Even when the description is explicitly of a natural scene, Ovid's palpable effect is artificial. [Hunt:1986, p.43]

Hunt follows the chapter “Ovid in the Garden” with “Garden and Theatre”:

The organization of garden space to accommodate and present visitors with the Ovidian narratives discussed in the previous section clearly recalls contemporary theatrical experience in ballets, intermezzi, drame per musica, operas or masques. Especially when the Ovidian incidents were animated by hydraulic machinery and thus moved in front of spectators, often to the accompaniment of music as at Pratolino, the equivalence of garden and theatre was palpable. Indeed, the relationship of theatre and garden in late Italian Renaissance was particularly close and indelibly marked the English reaction to the latter.

The progress of that relationship need not concern us in detail. It is necessary simply to rehearse what is by now established in theatre history, namely That Renaissance gardens came to play a significant part in the search for an appropriate Theatrical Space, a lieu théâtral or luogo teatrele. [Hunt:1986, p.59]

As we mentioned before, the ancients used to invest or mark a space with numinous objects. An interesting example we already cited was that of the osilum of the Roman world, related to similar votive practices in Greece, Egypt, and the greater Mediterranean. Osilums, through their Renaissance revival, are direct predecessors of roundels in English Elizabethan gardens.

Roundels were arranged in English gardens similarly to the stations of the cross in churches, but their subjects were often classical myths and allegories imbued with Renaissance sensibilities of New Learning and rediscovery of antiquity and historical continuity.

There is a speculation among musicologists about a possible connection of roundels and their programmatic walk to the development of the musical form marked rondo, as we know it later in the time of Mozart and Beethoven. The walk in the Elizabethan garden from roundel to roundel may have bean accompanied by music, probably similar to the music accompanying the Renaissance alchemical emblems we cited before.

Our study of roundels leads us to the concepts of pre-designed or implied spatial and visual arrangements and introduces us to the element of a walk, dance, or ritual—as well as the aspect of duration, time, into the mix.

The journey from roundel to roundel, when enacted in the Elizabethan gardens, perhaps revealed and re-invested the space with the sense of its unique spirit, its genius loci and its associated themes.

Image 13. Detail of Church Pavement, Ravenna, Italy.

Image 13 opens up the discussion and reading-of-images further, in the field of performance. The importance of pavement designs—particularly of the labyrinth—as a matrix for dance and dramatic enactment have been largely overlooked. Mosaics and floors have often been studied as surface decoration. The markings carrying hidden choreographic notation have been lost over time.

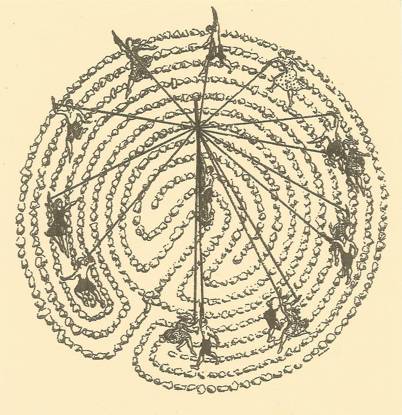

Image 14. Reconstruction of a Labyrinth Dance by Lars-Ivar Ringhom in 1938. [Kern:1982, p.405]

Lars-Ivar Ringhom, in 1938, created the drawings presented in image 14, which connects the maypole to the labyrinth and a dance sequence to the arrangement of ribbons around the pole.

Hermann Kern, in his definitive book Labyrinthe, Includes Ringhom's drawings as examples of an analysis of labyrinths, although he disagrees with Ringhom's interpretations.

Regardless of issues of archeological confirmation that labyrinths were used with a pole or not, Ringhom's drawings are important in the exploration of scenic investments into places, and they acknowledge possible visual and programmatic readings.

Image 15. Cathedral Floor from Southern Italy.

Images 13 and 15 show cathedral pavements in Ravenna and southern Italy. The famous cathedral labyrinth at Chartres, not illustrated in this paper, has provoked many published studies of its possible interpretation. But for the sake of honoring and understanding choreographic insertions as means of investing a place with a symbolic sense, we shall spend some time with another famous pavement—that of the Presbytery at Westminster Abby.

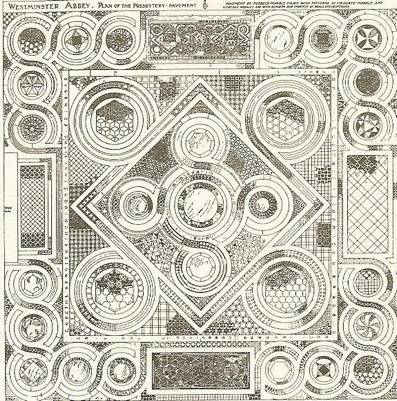

Image 16. Plan of the Presbytery Pavement known as the Cosmati Floor. Westminster Abby, London. Drawing published in 1924 by the Royal Commission on Historic Monuments.

The Presbytery Pavement at Westminster Abby known as the Cosmati Floor (image 16), named after the Cosmati Brothers, the Italian master builders who built it in 1268, is reasonably well preserved, but it is only possible to see it once a year when the carpets and chairs are removed. The floor design is 7.57m square. (The floor's day of viewing is advertised in Westminster Abby's publications, but it takes some organizing.) Some architectural critics and historians, such as Keith Crichlow, put out the hypothesis that the pattern is a choreographic notation with steps and sequences marked. According to Richard Foster, who reconstructed inscriptions on the floor from historic records, part of one inscription reads:

SI LECTOR POSITA PRUDENTER CUNCTA REVOLVAT HIC FINEM PRIMI MOBILIS INVENIET…

(If the reader go carefully round all this he will come to the end of the Primum Mobile [First Mover]) [North: 2004, p.211]

The other inscription around the central circle, made of Egyptian onyx, reads:

SPERICUM ARCHETIPUM GLOBUS HIC MONSTRAT MACROCOSMUM

(This spherical ball shows the Macrocosmic archetype.) [North: 2004, p.212]

In the bands around the circle and the square are elements with an odd spacing and rhythm that hint of a possible use beyond decoration. This pavement belongs to the international language of architectural traditions. It belongs with the decorative and ambulatory pavements in cathedral and ritual places similar to the throne at Anagni Cathedral, built by the same Italian craftsmen.

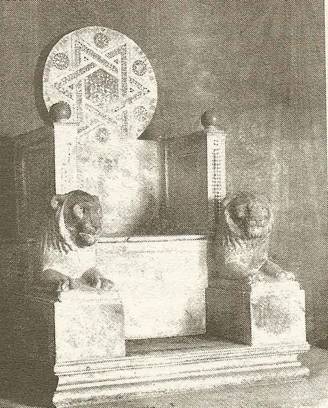

Image 17. Throne at Anagni Cathedral built by the Cosmati brothers. Twelfth century.

Image 17, the throne at Anagni, is an example of a scenic element infused with associations that invests a place with a meaning that would not be there without it.

The throne in question was plainly meant to imitate Solomon's, for it had lions on each side and the rounded back as did his. [North: 2004, p.268]

Through evoking King Solomon's throne and biblical associations, the authority of the church was implied. Those references were understood by contemporaries and subsequent users of the cathedral. Anagni was a favorite place for popes over the centuries. It was at this cathedral, and in the presence of the throne made by the Cosmati Brothers, that Richard Ware was confirmed as the abbot of Westminster by the pope in the twelfth century. Subsequently, he commissioned the Cosmati Brothers to create the Presbytery Pavement for Westminster Abby.

Image 18. The Ambassadors painted by J. Holbein, 1533.

The twelfth century Cosmati Pavement appears as a scenic element in the sixteenth century painting The Ambassadors by Holbein. There are many discussions by a number of authors about the similarities, dimensions, discrepancies, and reason for the pavement's inclusion in this double portrait. One thing most commentators on the painting agree upon, in different degrees, is that the allusion was deliberate. Like the rest of the painting, the careful arrangement of all the objects sets the scene for us to appreciate the culture, achievement, and preoccupations of the two men portrayed as representatives of their age.

The brief inclusion of this painting in a paper about scenic elements—and the painting's connection to the Cosmati Pavement—demonstrates the way a significant allusion can be infused into a scene for the sake of a reference to a place. The painting depicts a definite moment in time and can be read on many instruments: 10:30 on April 23, 1533. [Sejka: 1964, p. 181] Just as the throne at Anagni Cathedral refers to another time and a mythical throne, the pavement in the painting links the ambassadors to a twelfth century ambulatory symbolic journey. This stretching of context is partly emphasized by the anamorphic skull on the painting's floor, a mysteries object, which could be only comprehended by walking around the painting.

Here we can make a connection back to the osilums and their descendants, the roundels, as markers of a symbolic journey, a type of performance facilitated by scenographic elements investing a location with a sense of place.

Root Metaphor, Tragoi, Maenads, Satyrs and Companions of Dionysus

Now that we have established that instances of scenic expression can be found and observed in unlikely places, we can explore a possible root metaphor and motivation of theater practice. Not only spatial arrangements and place-markings, but also the designs which include duration and sequencing as possible choreographic scores, imply a symbolic journey. These symbolic journeys can be gleaned from pavement decoration, sculptures and paintings, or hinted at by topiary.

The examples from material culture cited so far in this paper may prepare a way to ask some questions and explore and extend the root metaphors of theater. The examples may also further our discourse on the investment of non-theater space with mytho-sculptural elements for a performance.

In searching for a root metaphor of the theater phenomenon as we know it in the West, it may be interesting to look at performances and rituals in the ancient world of the Mediterranean, which was—and still is—a confluence of currents from Africa, Asia, and Europe. As we shall explore, some buildings, events, and objects may not only be sources of factual information, but they may also offer ways to approach the reading-of-images of antecedents of contemporary theater practice.

Here we are not interested in proving that any hypotheses are right or wrong; that is not the intent of this paper. The fact that the theater, like ritual, has existed and persisted since antiquity is the starting point for our engagement and thinking.

We might consider pointing out possible root metaphors of the theater phenomenon and, by extension, of scenic presences in public places. To do that, it may be interesting to look at festivals associated with the origins of theater.

A simplified summary of the origins of Greek theater—compiled from many sources and cited in the bibliography—can be expressed like this:

It is the worship of Dionysus that the dithyramb and drama owe their origin and development. The dithyramb was a chorus of approximately fifty men and boys assembled to honor Dionysus. It has been conjectured that, over time, one member of the chorus began to sing separately from the rest, marking the beginning of the emergence of drama in early Hellenic culture.

It is commonly accepted that the grave of Dionysus was at Delphi in the innermost shrine of the temple of Apollo. [Frazer: 1922, p.389] Sacred offerings were brought to the grave of Dionysus there. In every second or third year (historians differ on this), and after spending an interval in the lower world, Dionysus was born anew.

The most ancient representation of Dionysus consisted of wooden images with the phallus as the primary symbol of generative power.

In Attica, Dionysus was worshipped at the Eleusinian mysteries with Persephone and Demeter, under the name of Iacchos, as brother or as bridegroom of Persephone. At Delphi, Dionysian festivals proceeded from the innermost sanctuary of Apollo to the neighboring mountain of Parnassus.

As a god of the earth, Dionysus belongs, like Persephone, to the world below as well as the world above. The death of vegetation in the winter was represented as the flight of the god into hiding from the sentence of his enemies, but then he returns again from obscurity, or rises from the dead, to new life and activity.

J. Fontenrose, in his Python: A Study of Delphic Myth and Its Origins says this about Dionysus:

Our impressions of Dionysos have been the opposite: he has seemed to be a god of springtime and summer, of harvest and vintage, of renewal of life and the ripening of fruits; and so he often was. But he was also a god of death, a ruler of the underworld, like Osiris, with whom he was identified. For there is a good deal of evidence that links him with Hades and the dead. [Fontenrose: 1980, pp.379-80]

The ancient historian Plutarch in his On Isis and Osiris, says:

It is proper to identify Osiris with Dionysos.

Further in the same text, Plutarch records the conversation with the high priestess at Delphi:

That Osiris is identical with Dionysos who could more fittingly know than yourself, Clea? For you are at the head of the Thyiades of Delphi, and have been consecrated by your father and mother in the holy rites of Osiris.

H. Jeremiah Lewis in his website, Sannion's Sanctuary, sites thirty-two quotations–including the two previously mentioned–on the shared identities of Dionysus and Osiris. Here are four more:

There is only the difference in names between the festivals of Bacchus [Dionysos] and those of Osiris, between the Mysteries of Isis and those of Demeter. –Diodorus Siculus, The Library of History, 1.13

Osiris, they say, was reared in Nysa, a city of Arabia Felix near Egypt, being a son of Zeus; and the name which he bears among the Greeks is derived both from his father and from the birthplace, since he is called Dionysos. –Diodorus Siculus 1.15

Dionysos and Osiris are the same, who are called Epaphus. –Mnaseas

Osiris is he who is called Dionysos in the Greek tongue. –Herodotus 2.144

Osiris's wife Isis discovered the grains of wheat and barley, and Osiris taught humanity how to plant the seeds and how to tend and water the crops; how to cut, harvest, dry the grain, grind it to flour, and make it into bread. He showed them also how to plant vines and make wine.

Image 19. Ship of Isis from the walls of temple on the island of Philae. [Description De L'Egypte: 1809, Vol. I, pl.11]

Our example 19 is of the Ship of Isis from the walls of a temple on the island of Philae.

The image represents the sacred ship with collected elements of the dismembered Osiris before his reawakening by Isis. To understand the central role this example of a scenic processional object plays in this paper, we shall attempt to summarize the story behind the ritual performance of the Ship of Isis. The story's recapitulation is from number of sources cited in the bibliography.

The Story of Isis and Osiris

Osiris was king of Egypt, beloved by his subjects. His brother, Set, was jealous of his successes and plotted against him. Set secretly obtained his brother's measurements and had a beautiful casket shaped in the form of a man made to fit Osiris. Set then invited seventy-two people—mostly conspirators—to a celebration, and he invited Osiris.

At the height of the celebration, Set unveiled the casket and promised to give it to anyone who could fit in it. Everyone tried, but only Osiris fit perfectly. As soon as Osiris was in the casket, Set shut the lid and sealed the casket with molten lead. After that, he threw the closed coffin into the Nile.

Isis was bereft at the murder of her husband and searched for the casket throughout Egypt and other countries.

She found it at the roots of an ancient tree in a place far away from Egypt. After that, Isis brought the coffin home for a proper burial.

While she was preparing for burial rites, she hid the coffin in the rushes of the estuary of the Nile.

As fate would have it, Set found the casket while out hunting and in a fury, he chopped the body of Osiris into pieces, and scattered them throughout the land of Egypt.

Isis again had to search for the parts of her husband. Eventually she found all the parts but the phallus, which had been eaten by a large fish. By her power she reconstructed the missing part, and produced it out of herself. She wrapped Osiris in bandages drenched in beneficial herbs and breathed life back into Osiris's body. It was then that Horus, the original Pharaoh, ruler and protector of people, was conceived.

Scenic Ship

Image 20.Sacred Ship of Isis. [Garrigue: 1851, pl.470]

Once a year in ancient Egypt, a beautiful scenic model of a ship was carried from the Isis Sanctuary to the Nile. There, it was floated or transported to the other bank, and celebrated in a series of ritual performances before returning to the mother temple. This ancient Egyptian ritual performance continued as the Greco-Roman festival of Ploiaphesia, also called Isidis Navigum. The Festival of the Ship of Isis celebrated Isis as Goddess of the Sea. It persists as the Christian festival of Stella Maris, during which a statue of Mary is carried on boats in Catholic countries. A similar continuity occurs in Greece and other Mediterranean countries with a Byzantine (Eastern Orthodox) rite, where young boys send models of little boats to the sea before Easter.

While studying Tarantella and other women's dances, the author of this paper inadvertently came to the Dionysian festivals and other regeneration rites and celebrations. As we described before, the central object of the Eleusinian Mysteries is of interest to us as it was a minimal, portable, scenographic element with the power of investing and marking the place and signaling its spirit. The Eleusinian Mysteries of Demeter and Core/Persephone are very similar to the tri-annual celebration of the return of Dionysius.

In summing up our thinking about root metaphors in the western theater tradition and its scenography, we present the following open questions:

- Whose grave was it in the sanctuary of Apollo's temple at Delphi? Was it Dionysus? Osirus? or perhaps Python?

- Was the sanctuary at Delphi build around a more archaic ritual center?

- How do we understand the paradox that Dionysus—a relatively young god—has such ancient and archaic roots whose temple is centered around an even older scenic element?

- Did the festivals of Dionysus continue the rituals of mourning and jubilation over the seasons' return from some older times?

- How do we interpret accounts of ancient authors and historians—and speculations by a number of scholars—about the association of Dionysus with Osiris and Demeter with Isis?

- Was the core revelation of the Eleusinian Mysteries akin to the Isis celebrations, particularly to the ritual procession of the Ship of Isis, Isidis Navigum?

- Are the tragoi, the goats, of the dithyramb (the chorus of approximately fifty men and boys assembled to honor Dionysus) and the Maenads (the cohort of women and girls amid the mountain at night) a part of the same festival origins?

Image 21. Images from the opening scene of Artship's production, Same River Twice. 2004.

To link the ancient material with contemporary practice, the following images (image 21) were projected while the story of Isis and Osiris was presented in Prague at the 2007 PQSI conference. The images, although unrelated in subject matter, are similar in some way in the usage of a prop. Here it is an attempt to integrate past and present through juxtaposition.

Image 22. Publicity image, collaboration of Slobodan Dan Paich and Sabine Grande, for Artship's production Same River Twice. 2004.

Image 23: Any ship or boat, just by itself, is an experience to behold—even without any theatrical intention—particularly when the vessel is of an unknown type to the spectator. The example here is of one such vessel: it is an image of a gajeta, an ingenious boat from Komiza, an Adriatic island off the coast of Vis, Croatia. As you see, the gajeta has a remarkable scenic quality.

Image 23.Life-size operational reconstruction of Gajeta Falkusa. [Photo from an article by Dr Josko Bozani?, Brodarski Institut, Zagreb. 1996.]

Image 24 documents the annual burning of an old gajeta boat in Komiza, at the feast of Saint Nicholas, the patron saint of mariners, seafarers, and children. It is an ancient ceremony, adopted by the local Christian church. The festival consists of a single scenic element and takes place annually during the shortest days of the year—around the same time of the year that the Greater Dionysia were celebrated in pre-Christian times. The boat burning is an expression of a sacrifice and purification in anticipation of the return of longer days, fecundity, and a plentiful harvest from the sea.

Image 24. Burning of an old Gajeta Boat. Komiza. [Photo from an article by Dr Josko Bozani?, Brodarski Institut, Zagreb. 1996.]

The images here are from a small UNESCO-sponsored book describing the reconstruction of the ship and its journey from Komiza to Lisbon for an international exhibition. Dr Josko Bozani?, playwright, scientist, boat builder, and citizen of Komiza, was the author of the articles in the UNESCO booklet and a member of the expedition.

Image 25. Kaledari in Friuli, Northern Italy. Photo by Pellis. [Ciceri: 1980, p. 119]

Before we turn to a few examples of contemporary re-investing of public space with scenographic and theater elements, let us look at some ritual ambulatory performances of the Kaledari. This winter ritual performance is widespread west from Alpine regions in Europe throughout the Balkans, and across the Pannonian Plain; traces of it can be found in Czech, Polish, and Russian territories to the north, and Romania, Bulgaria, and all the way to the Black Sea to the east. The ritual consists of costumed men wearing head masks of a goat/stag/devil type who are covered in sheepskins with the wool on the outside. They are so covered and disguised that they are hard to recognize as individuals. The Kaledari are intended to be frightening to malignant spirits and help rid their community of potential difficulties. In some regions one of the men is dressed in a woman's clothing, and his performance allows for bawdy, erotically forward, procreative gestures without ruining a maiden or matron's reputation. The Kaledari go from place to place and knock on all the doors. The moment they arrive or are heard nearby, the place is transformed. With bells attached to their limbs, they dance around the house, moving furniture and fighting invisible spirits with wooden swords. There is humor, as everyone knows that it is play. The band of Kaledari men are beautifully bonded, and young boys cannot wait to be big enough to be admitted into the performing group. It all happens on and around the shortest day in the year and it is another example of a festival of regeneration where an everyday routine is disrupted by scenic elements and a performance/ritual. Through humor, dressing up, music, and noise, the Kaledari may be a catalyst to dispel collective fears and reconfirm communal closeness.

Images 26-28. Inflatable Sculpture. Great Gorges Community Arts Center. Liverpool docks, England. 1969.

For the moment, we shall leave ancient and traditional examples and describe and reflect upon a number of contemporary examples initiated and carried out by the author of this paper over a period of approximately thirty years. Not knowing anything at the time of the Kaledari's roaming traditional performances, our first project, illustrated in images 26-28, was also ambulatory. A sculpture was mounted on a track that moved every two weeks to another location in Liverpool during the summer of 1969. Twelve artists, dancers, actors, and volunteers animated them with household vacuum cleaners attached to their backs. Meanwhile, below the sculpture, stories were told, read, and enacted throughout the day.

The point of the inflatable sculpture and the track—temporarily infusing an unexpected meaning into the urban spaces it visited, does not need to be labored over. The project, commissioned by the Great George's Community Cultural Centre in the Liverpool docks, England, is mentioned for the sake of the development this paper.

Images 29-31. Scrap Metal Sculpture Great George Community Cultural Center. Liverpool, England. 1968.

The scrap metal sculpture in images 29-31 was also created in Liverpool the year before as a climbing sculpture with an accompanying puppet show. The audience, mostly children, sat and played on it while watching the show. The puppets and the play were made by older children and the artist in a very short time. The sculpture—looking something between a sports car and a steamroller—offered multiple opportunities for play. Its shape seemed to inspire endless imaginary journeys. The fact that it did not move provoked vigorous imagining.

(In an attempt to hint at possible thinking of typology, we will underline the summaries of the projects to follow, as above.)

Images 32”38. Spring Moon, the Persephone myth retold and enacted for the occasion of reopening of the oldest public swimming pool in the North Beach district of San Francisco. 2005. Photos: Robert du Domaine. 2005.

In 2005, Artship Ensemble was invited by friends of the DiMiaggio Park and Playground to create a piece for the reopening of a newly refurbished public pool in the North Beach district of San Francisco. The Ensemble responded with the staging of the Persephone Myth, enacted in and out of water and at different edges of the pool. The commissioning group and the Artship Ensemble were interested in creating culturally significant work that was both an art and public commemoration piece, liberated from the clichés of public openings and yet being an element of one. The intention was to engage the imaginative, poetic side of the diverse neighborhood, give an unexpected but approachable performance, and mark the occasion with a memorable, once-in-a-lifetime event. Fabrics were the main scenographic elements for that purpose. Some of the fabrics had hundreds of ping pong balls sewn into them by volunteers, affording floating scenic elements on the surface of the water. Other fabrics were allowed to trail from the edge, through shallow parts of the pool, all the way to the bottom of the deepest part. Some extremely large off-white silk fabrics were covering poolside furniture and objects. Although the top of the fabric was dry and sensitive to breezes and movement, the lower ends plummeted straight to the bottom with the water's weight. Hades performed at one end, surrounded with life-size sculptures of human figures covered with semi-transparent black synthetic silk. Clad in a generous black toga that was decorated with silver grommets, he beat a large dark drum. On the other end of the pool, in the Upper World of Persephone's mother, bits of color contrasted and harmonized with the general off-white of that area. The performance took place along three edges of the pool while the audience sat or stood at the larger forth side.

The majority of the performance's color was in the costumes: A figure in an orange dress and pantaloons characteristic of Hindu and Muslim women's clothing entered the water fully dressed as pilgrims do in many cultures. This reference was not lost on Californian audiences. Persephone's mother, still wearing black, celebrated her daughter's return with a long red cloth she danced with. Persephone and a welcoming childhood playmate were wearing white, but she also wore an open wrap-around green and blue pleated skirt. The African American narrator who mingled with three musicians wore a simple regal beige robe. The music, specially created for the occasion, was played on cello, Caribbean steel drum, and accordion. The juxtaposition of modern pool architecture, the unexpected use of scenographic fabrics, and the restrained, conscious use of color in the performance costumes created an atmosphere which was very similar to images that manifest in the dreaming process.

The amount of detail included about the performance here is to help us look at image-making and interdisciplinary image-reading in connection to temporary place-making for a performance. This leads us to an open question that may be central to this paper:

Is any theater setting a nexus for the inner world of human psychology, where the intangible realm and the material world can coexist and unite in a memorable experience for the audience?

In discussing the scenographic characteristic of place-making”both in a performance setting and as an imaginary space”another sub-theme emerges: the biological needs of the human nervous system for fantasy and involuntary image-making.

After seeing the performance of Artship Ensemble's Persephone myth performed in the swimming pool, Dr. Paul A. Pangaro, a theoretician of conversation theory and cybernetics and a contributor to discussions on artificial intelligence, wrote this about it:

…my scientific training holds that our nervous system has as its fundamental purpose to maintain SYNCHRONIZATION with our environment. This started with pure physical survival, of course, but generalizes to language and culture. This encompasses evolution of all kinds. The homeostatic processes of the body are synecdoche, so to speak, for our living together in the world…

What is the role of cultural experience, theater experience, and unique scenographic place-making in this characteristic of the human nervous system to continuously adjust and respond to the environment?

D. W. Winnicott articulates a response in his writing on the transitional object and transitional space:

The place where cultural experience is located is in the potential space between the individual and the environment. The same can be said of playing. Cultural experience begins with creative living first manifested as play. [Winnicott: 1971, pp. 96-97.]

In another place he says:

It is in the space between inner and outer world, which is also the space between people”the transitional space”that intimate relationships and creativity occur. [Winnicott: 1951, pp. 98-99.]

In the scope and expertise of this paper we are only able to point to the issues raised by the existence of temporary scenographic elements in the outer environment. We approximate their impact on spectators through studying their feedback. As of yet we have not carried out a systematic study of the relationships of poetically created imaginative objects, situations, or places in relationship to the continuous image-making process of our nervous system. We know from experience and literature that we compensate and help ourselves every night, through a dreaming process full of images. How we read them (if we remember them) is an open question. Can we read the images created in art, performance, and entertainment by the same means? Would a cultivation of performance literacy and multidisciplinary transliteracy help deepen our response and understanding of the function of cultural needs?

Typology and Sub Categories of Site-Specific Performance

The examples so far, and examples to follow, are included with the intention of continuing and eliciting our thinking on typology, and the theoretical and practical implications of creating a theater setting without a theater building. Examples 39 and 40 are instances of a simple redefining of a place with a scenic object and performers. It is different from the next example, image 41, of a site-specific project related to the site, inspired by—and only possible on—that site. The Mirrors in the Forest Project is possible in any forest with any amount of mirrors and performers.

What name or definition would we give to this type of scenic intervention?

Images 39-40. Mirrors in the Forest, violinist Edvin Schmitz, singer/performer Mira Musich, 1989.

Image 41. Growing Up Invisible. Site-specific performance in the stables of an historic house. Commissioned by Pardee Home Museum. 1995.

In 1995, Artship's performance company, then called the Augustino Dance Theater, worked closely with the Pardee Home Museum (home of Mr. Pardee, an early Governor of California). The two entities collaborated in creating a performance about life in the stables behind the Governor's house. It was a performance based on oral histories of house owners and their servants collected by the museum. The audience sat on specially made pews stained the same colors as the old stable's wood. Musicians hidden in the tiny attic of the stables oozed music, which came muffled through the rafters. The musicians were discreetly, almost invisibly, conducted from the back of the audience through closed circuit television. The big house was also wired for sound, so from time to time, a recording of the awkward piano practice of the governor's little girls, long deceased, could be heard. Every inch of space and every moment was linked to the history of the place. It was an embodiment of the site-specific genre.

Image 42. Icarus. Augusto Ferriols in solo performance on the tower of the Moorish Castle at Gaucin. Southern Spain. 1990.

Loosely based on the Icarus myth, the performance documented in image 42 was conceived with verticality and the space of air and sky in mind. People present looked up to see the event. The unspoken poetic notion was to be in relationship to the vastness of space hinted at by the distance of the figure of the performer. The mythological element was both a communication device and a link to the atavistic myth-making aspect within the spectator. It is a site-inspired, but not necessarily site-specific, mythological association. The figure with wings is a scenic theater signifier acting to thematically reinterpret the site.

Image 43. Windfall of Memories. A Collaboration of Artship and number of local and city agencies to revitalize amphitheater in Arroyo Viejo Park. Oakland, California. 1996.

Image 43 is from a performance at Arroyo Viejo Park in East Oakland. There, an amphitheater was built in late 1930 as a WPA Project—the same program that built the Golden Gate Bridge. This amphitheater was popular until 1960 when it became a nexus of crime and illegal activates. A coalition of neighbors invited Artship artists to animate city agencies to repair the amphitheater and support a series of daytime performances in the summer. Unlike the Persephone myth project, a community commissioned art piece, at Arroyo, it was important to give voice to and represent as many people as possible. Hence the image of the reluctant performer, overcoming his shyness by hiding inside a scenic element. His commitment to help reclaim the space overcame his perception of his awkwardness. Joan Maeda, the stage designer of New York's La Mama Theater, worked with the Artship artists, interns, and volunteers to create the scenic elements for the show. The author of this paper worked to elicit memories of all kinds from the community and let them flow through the performances. Reclaiming Public space for community use was a main driving force of the project. It was more of a people-specific than a site-specific performance.

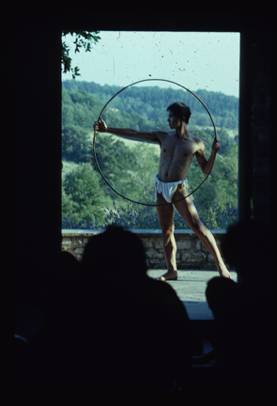

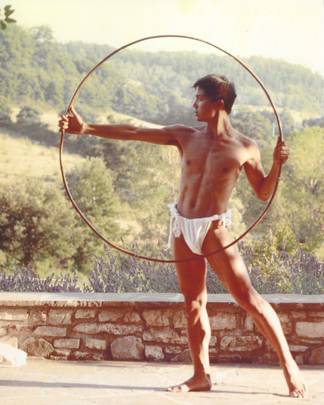

Image 44. Rondo Dance. Augusto Ferriols. Tuscany. 1991.

Rondo Dance was a signature dance of the Augustino Dance Theater, the original name of Artship's performance company. Conceived and choreographed by Slobodan Dan Paich for and with Augusto Ferriols, image 49 shows the performance given on the terrace of an 400 year-old house in Tuscany, with the audience seated inside. The dance was inspired by three strands: first, a painting of Ganymede with a hoop from an ancient Greek vase; second, roundels, osilums, and other life-cycle allegories in ancient gardens; and third, the music form of rondo. Rondo is a type of composition in which one section recurs intermittently. By Mozart's time, the rondo had evolved into a standard pattern and was much used for the last movement of a sonata or concerto. A simple rondo is built up in the pattern of ABACADA, where A represents the recurring section or rondo-theme and B, C, and D represent contrasting sections or episodes. The rondo theme can undergo some variation in its reappearances.

Image 45. Rondo Hoop as a Proscenium. Augusto Ferriols. Tuscany. 1991.

Rondo Dance was contextualized by the hoop, which became a proscenium, scenographic element, prop, and symbol. The dance went through a number of variations—always returning to its original theme. The minimal and transformative narrative offered by the hoop integrated many meanings through the usage of a single object.

Psychologist James Hilman, in his book Myth of Analysis, has said that poetic language intensifies meaning by packing many implications and references into the small space of a word or phrase: that a poem miniaturizes, and is like a computer chip or an optic fiber in that it carries many messages simultaneously. [Hillman: 1972, p.207]

The piece's journey and continuous transformations created through the use of a single scenic element inadvertently framed elements of the surrounding landscape. The dance became inseparable from—and specific to—any location the piece was performed.

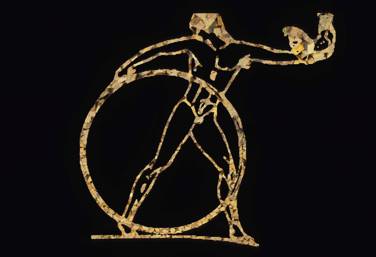

Image 46. Contemporary rendering of Ganymede With a Hoop after an ancient Greek vase, the logo of the Dance Theater 1988-2001.

Image 47.In Place”Horse and Canoe Project. Tom Franco. Mountain Lake Park, San Francisco. 2006.

The starting point for In Place”Horse and Canoe addressed the meeting, clash, attempts at domination, parallel existence, and survival of cultures. The outdoor performance was inspired by two modes of transportation that are signifiers of the two cultures in the history of San Francisco: Spanish and Native. The site was one of the American Indian sacred sites and a spot where the de Anza expedition from Mexico stopped in 1776 and founded the Presidio of San Francisco. The performance was intended to be a mixture of native folklore, heroics of conquest, and contemporary staging. The In Place”Horse and Canoe performance is as specific to the site as it is to the many layered and contradictory histories of the site.

Image 48 - 49: Co-Existence. Performance with, and around, fifty egg-shaped sculptures of all sizes. A collaboration of the Neighboorhood Parks Council and Artship. Lafayette Park, San Francisco. 2005.

The performance in image 49 was an example of myth-making with objects. Artship's performance celebrated the co-existence of different qualities in the same space: one world that is inhabited by both imaginary and real people. Revelers at the annual meeting coexisted with the performers: a band of itinerant musicians, dancers, and actors from all over the world. The performers on the ground were as if secular, contemporary, art magi: they brought intangible gifts to the evening as a singer or storyteller might. In the trees, several “ambassadors of the people of the air” cared for and worked in their own elements, as if inadvertently performing at the gala. Co-existence is a continuation of Artship's collaborative work towards redefining delight in, and involvement with, parks.

The performance's experiments celebrated the co-existence of different qualities sharing the same space.

Images 50-53. Icarus Images. 1990.

Images 50 through 53, Icarus Images, were created before the invention of Photoshop to project onto public and historic buildings. They are our final examples from contemporary practice where a mythological element temporarily infuses a place with a new meaning as an imagination trigger.

Image 54. Seeking a Bride from a Distant Village. Inuit ritual journey photographed by Edward S. Curtis, c.1898.

Our final image depicts a ceremonial journey where a young man, accompanied by a medicine man dressed as an eagle, seeks a bride, an ingenious ritual which understands the necessity of reinvigorating the genetic pool of a small community. The journey's character is a fertility rite. Its deep intentions”somewhere in essence”may be similar to the intentions of the Ship of Isis ceremony. Although similar in a mythological intention, the two rites differ greatly in geography, climate, sense of time, and history. One thing they have in common is humanity's need to symbolize and mythologize in its desire to continue.

Genius Loci and Need For Stories?

In conclusion and through the examples cited we can say that each place invested with its guardian spirit is also associated with a myth, hearsay, and a story.

The relationship of story and place may be provoked by an idea that in the archaic recesses of our being we ward off unbearable levels of irrational anxiety through the need for, and the mechanisms of, personification. To personify is to represent things or abstractions as having a personal nature, embodied in personal qualities. Personifications are usually embodied in a place or scene set aside for communal gatherings: a place for a symbolic ritual or a performance. Personifications manifest in a form of statuary, ritual markings, buildings, gardens, processions, and ambulatory performances discussed throughout this paper.

When personification acquires duration and it begins to exist in time, a rudimentary story may begin. This embryonic story, an individual inkling, finds great relief in joining the established flow of existing stories and well-known myths. That may be why children love hearing old stories over and over again.

Although the word personification implies a human face or figure, the investment of natural and human-made objects and animals with certain qualities of soul or spirit, i.e., animism, are manifestations of the same process.

The phenomenon of tarantism, the multi-faceted manifestation of illnesses and “moods” caused by the bites of the tarantula spider”and its cure through the dance of Tarantella”are living examples of the process of personification. In the ritualized interplay of affliction and recovery, a reintegration of the affected person into the community takes place through dance.

The positive side of this personifying, a story-seeking function, is to give us a sense of belonging, of community, and, to use Phillippe Borgeaud's term, recovered closeness. The negative side of the personifying process is investing others with our panic and creating chauvinism, racism, and similar manifestations.

Just like the physical body continuously works to keep body fluids moving, temperature almost constant, the stomach acid at manageable levels, etc., so does the psychological self produce compensating, relieving images and nonverbal scenarios, or proto-stories to help us deal with life's complexities.

The continuous interplay of panic and recovered closeness is central to family or community life; it never goes away. Just as babies need continuous reassurance and feeding, so do adults, but in sophisticated ways which reinsure them of implied communal bonds.

Genius Loci, Scenographic Incident, and the Role of the Imaginative Function

In summary, to potentially learn and discover, we could point in a direction of understanding some aspects of the inner world of voluntary and involuntary imagining: the imaginative function. It may be useful to attempt to reflect upon our human ability to nurture ourselves through sublimation, dreaming, and its cultural expressions. The traditional concept of genius loci, spirit of place”with its number of meanings ranging from the special atmosphere of a place, through human cultural responses to a place, to notions of the guardian spirit of a place”may offer a common link to the archaic layers of our socialized self and shed some light on the rituals of common anxiety-release through personifications and enactments.

The imaginative process is significant for our recovered closeness. We do this nightly in dreams, where, through dynamic images and an active process of personification, we self-heal and inadvertently deepen self-knowledge. This personifying function and its manifestation as rudimentary non-verbal sequences, with narrative potential, could be a starting point for studying and understanding the need to invest places with mytho-sculptural elements for performance, ritual, or recollection. Investing a place with a spirit of place, aided by scenic elements, is a recognizable, observable cultural phenomenon worthy of reflection and study.

Bibliography

Edward Allen, Stone Shelters, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1969.

Margarete Bieber, The History of the Greek and Roman Theater, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1961.

Philippe Borgeaud, The Cult of Pan in Ancient Greece, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.

Josko Bozani?, Gajeta Falkusa: Razvoj drvene brodogradnje istocnog Mediterana tijekom 18. i 19. Stoljeca, Zagreb: Brodarski Institut, 1996.

Luigi Ciceri, Religiosita Popolare in Friuli, Pordenone: Edizioni Concordia 7, 1980.

Description De L'Egypte, ou Recueil des observation et des recherches qui ont ete faites en Egypte pendant L'Expedition de L'Armee francaise, Publie par les orders de sa majeste L'Empereur Napoleon le Grande, a Paris, De l'imprimerie Imperial, 1809, Cologne: Taschen, 2002.

Joscelyn Godwin, Athanasius Kircher: A Renaissance Man and the Quest for Lost Knowledge, London: Thames and Hudson, 1979.

Susan Foister, Ashok Roy, Martin Wyld, Holbein's Ambassadors, London: National Gallery Publication, 1997.

Joseph Fontenrose, Python: A Study of Delphic Myth and Its Origins, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1959.

Sir James George Frazer, The Golden Bough, New York: The Macmillan Co., 1922.

Emanuele Greco, “City and Countryside in the Greek World,” Art and Civilization in Magna Graecia and Sicily, New York: Rizzoli, 1996, 233-242.

Johann Georg Heck, Iconographic Encyclopedia of Sciences, Literature and Art, New York: R. Garrigue, 1851.

John Dixon Hunt, Garden and Grove: Italian Renaissance Garden in the English Imagination:1600-1750, London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd,1986.

Hermann Kern, Labyrinthe, Munich: Prestel-Verlag, 1982.

Atanasius Kircher, Magnes Sive de Arte Magnetica (Opus Tripartium), Rome: Ludovici Grignani (Abbreviated Magnes), 1641.

Steven Lonsdale, Animals and the Origin of Dance, New York: Thames and Hudson, 1982.

Michael Maier, Atalanta Fugiens, Openheim, Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1969.

Bianca Maiuri, Museo Nazionale Di Napoli, Novara: Instituto Geografico De Agostini, 1957.

John North, The Ambassadors' Secret, New York: Hambledon and London, 2004.

William O. E. Oesterly, Sacred Dances in the Ancient World, Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2002.

Herbert William Parke, A History of the Delphic Oracle, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1939.

Jasia Reichardt, Play Orbit, London: Studio International, 1969.

Leonid Sejka, Traktat o Slikarstvu, Belgrade: Nolit, 1964

Oskar Seyffet, Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, Cleveland, OH: World Publishing Company, 1956.

Robert Turcan, Cults of the Roman Empire, Cambridge, Blackwell Publishers, 2006.

Donald Woods Winnicott, Playing and Reality, London: Tavistock/Routledge, 1999

Nicholas Yalouris, The Search for Alexander: An Exhibition, Boston: New York Graphic Society, 1980.

Slobodan Zecevic, Elementi Nase Mitologije u Narodnim Obredima uz Igru, Zenica: Muzej Grada Zenice, 1973.