Slobodan Dan Paich Comparative Culture Papers

Presented November 1-3, 2010 at the 4th Annual International ACSA Conference - The Visual Imagination: Across

Boundaries.

Bangkok, Thailand

Director and Principal Researcher

Artship Foundation, San Francisco, USA

River of Images

Interplay of External and Internal Image Making

Abstract

The elusive relationship between external cultural experiences and internal voluntary and involuntary image making is a starting point of this paper. Based on a number of contemporary projects and historic examples, open questions are asked about the imaginative function.

This investigation into the cultural phenomenon of imagination is done diachronically and cross-culturally. The attempt of the paper is not to prove any hypothesis, but to point to some societal and individual instances of doing and making, envisioning and imagining and their inter-relatedness. For that reason eight examples are chosen and discreetly paired off to offer a broad context for the inquiry. The four contemporary examples are from the art practice of the author of this paper, chosen from a span of projects carried out from 1969 to 2010. The historic examples are from the author's research and teaching in the field of comparative history of art and ideas also since 1969. The examples are:

Art of memory - Never seen before

Cicero's ancient mnemonic practice 1st century BC - Liverpool Inflatable 1969

Leaving poetic empty space - Filling the void

Chinese painting Guo Xi 11th century AD - Vertical Sculptures

1986 -1991

Imaginative seclusion - Bringing Fantastic into the everyday world

Gardens of villa Lante 16th century AD -

Persephone performance in the swimming pool 2005

Solitary Vision - Dialog of two imaginations

Goya's Caprichos 18th Century AD - Moira Roth and S. D. Paich

Exchanges 2008 - 2010

In closing, the paper addresses meta-questions provoked by the dependence on imaginative function by art and artifacts which reflect on the relationship of external material culture and internal mental processes.

Internal Voluntary and Involuntary Image Making

The waste field of human imaginative function is looked at in this paper in relation to the process of creating and experiencing art. Exploring, through eight examples, the human ability to nurture oneself through sublimation, dreaming, envisioning and its cultural expressions.

Just like how the physical body continuously works to keep body fluids moving, temperature almost constant, the stomach acid at manageable levels, etc., so does the psychological self produce compensating, relieving images and nonverbal scenarios, or proto-stories to help us deal with life's complexities.

The imagination plays a significant role in the internal psychological world, where experiences continuously ebb and flow between various principal nodes of sapient consciousness: that of conquering fears in the survival instinct, looking for and experiencing comfort of communal closeness and seeking ecstasies, reassurance and continuity in the procreative drive.

It also seems that parallel to survival and procreative imaginings, there runs an idolizing, ascending aspect of internal mechanisms that seek shared meaning and symbolic communication, give voice to transpersonal emblematic signs, and lead to cultural experience

The involuntary image making process happens nightly in dreams, where, through dynamic images and an active process of personification, we self-heal and inadvertently deepen self-knowledge. This personifying function and its manifestation as rudimentary non-verbal sequences with narrative potential could be a starting point for studying and understanding the need for expression. When personification acquires duration and begins to exist in time, like a sequence in a dream, a rudimentary story may begin to form. This embryonic story, an individual inkling, finds great relief in joining the established flow of existing stories and well-known myths. That may be why children love hearing old stories over and over again.

In the archaic recesses of our being we ward off unbearable levels of irrational anxiety through the need for, and the mechanisms of, personification. To personify is to represent things or abstractions as having a personal nature, embodied in personal qualities. Personifications are usually part of a space set aside for communal gatherings: a place for a symbolic ritual or a performance. Personifications manifest in forms of statuary, ritual markings, special buildings, representation of garden spirits and votive objects. Although the word personification implies a human face or figure, the investment of natural and human-made objects and animals with certain qualities of soul or spirit, i.e., animism, are also manifestations of the same process.

The phenomenon of Tarantism, the multi-faceted manifestation of illnesses and "moods" caused by the bites of the tarantula spider—and its cure through the dance of Tarantella—are living examples of the process of personification. In the ritualized interplay of affliction and recovery, a reintegration of the affected person into the community takes place through dance.

Cultural Experiences

The question about the beginnings of civilizations may open our discussion. Does a civilization start with an invention of writing or by the telling and re-telling, sometimes singing of myths and stories? Does recorded history start with cultivated imagination and remembered and repeatable oral traditions?

The worldview where oral tradition and the capacity of the brain to keep large amounts of information through mnemonic ordering of meaning and facts, may have a completely different relationship to externalization of information and expression than written record keeping. The imagination as a cultivated ability is significant here.

A glimpse into this worldview where the dominant operational systems are preserved and communicated through the oral traditions may help reconstruct the intellectual achievements of early humans. It also may help to better understand archeological and ethnographic remains of early cultures as different rather than primitive.

To come close to this worldview, presided by the oral traditions, we shall look at transmission of oral epic poetry:

In the seminal book on oral tradition and epic poetry by A. Lord, The Singers of Tales, there is a translation of a live interview with one of the last oral epic singing practitioners surviving among the mountain regions of Bosnia, recorded in the 1930's by M. Parry:

When I was a shepherd boy, they used to come [the singers of tales] for an evening to my house, or sometimes we would go to someone else's for the evening, somewhere in the village. Then a singer would pick up the gusle, [bowed string instrument typical of the Balkans used specifically to accompany epic poetry] and I would listen to the song. The next day when I was with the flock, I would put the song together, word for word, without the gusle, but I would sing it from memory, word for word, just as the singer had sung it... Then I learned gradually to finger the instrument, and to fit the fingering to the words, and my fingers obeyed better and better... I didn't sing among the men until I had perfected the song, but only among the young fellows in my circle [druzina] not in front of my elders... (Lord 85)

Now imagine any contemporary teenager first listening to an epic for several hours and then repeating it the next day from memory. By contrast, the non-literate shepherd boy was equipped with the necessary plasticity and capacity of brain, independent from written record and entirely confident in the ability of comprehension, retention and reproduction through oral means alone.

In the oral traditions, the expression and the memory are aided by rhythm (repeatable numeric sequence), a musical instrument (both a tally stick and an emotional anchor). Also by the use of a considerable number of pre-existing, repeatable storytelling conventions used across the repertoire for situations of grief, conflict, family, and love; a complex system in which the unity is held together by a number of distinct parts.

Aliveness of ideas, imagination, and arousal

The exploration of creativity from the problem-solving point of view is helped by the reality of the preconditions: a real-world issue and need, and, in the end, a measurable outcome. These concrete preconditions, if over-insisted upon, can obscure the elusive dimensions of an intense and internal series of events. After preparation and research comes a moment for a key idea to appear. Once the idea has risen out of the outer and inner unknown, it needs a form of life-force to propel it and sustain it. The idea's survival and generative life span depends on many factors. One element in the complexity of the creative process is the vital energy for the aliveness of the idea.

The recitation is approached from the general thematic over-sense to the particulars, the events of the story. The epic is held as a whole and as parts simultaneously, as a spatial and temporal continuum in the narrator's internal space.

1. Contemporary actors and storytellers are the keepers of oral delivery and mnemonics.

Art of memory - Cicero's ancient mnemonic practice 1st century BC

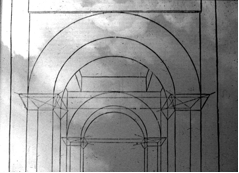

2. Rationale and order of architecture.

There is an art of memory cultivated by the orators of the ancient world as exemplified by Cicero, in his role as orator, public figure and a prominent politician of the last days of Roman Republic. His book De oratorere is a teaching compendium on technique and meaning of rhetoric and public speech. His writing is a classic in the field and deals, among other topics, with the art of mnemonics that rely entirely on imagination. British historian of ideas, Frances Yates (1899 —1981) pioneered the research on the lost arts of mnemonics for orators in her book The Art of Memory published in 1966. In her groundbreaking book, Yates quotes and analyzes classical thought on memory including passages from Aristotle and Plato. The quotes from her writing about Aristotle are also significant for this paper which explores the history and reality of the relationship of art and imagination:

"Aristotle's theory of memory and reminiscence is based on the theory of knowledge which he expounds in his De anima. The perceptions brought in by five senses are first treated or worked upon by the faculty of imagination, and it is the images so formed which become the material of the intellectual faculty." (Yates 32)

In her book Yates explores multiple attitudes towards memory, from Plato's notion of inborn, latent knowledge, and medieval theological speculations, to the renaissance neo-platonic relationship between memory and imagination. She continues summarizing Aristotle:

"Imagination is the intermediary between perception and thought. Thus while all knowledge is ultimately derived from sense impression it is not on these in the raw that thought works but after they have been treated by, or absorbed into, the imaginative faculty." (32)

Yates carefully chooses her summary to give an informed and critical base for her later explorations of the historic and allegorical relationship to internal and internalized images:

"it is the image-making part of the soul which makes the work of the higher processes of thought possible. Hence 'the soul never thinks without a mental picture'; 'the thinking faculty thinks of its forms in mental pictures'; 'no one could ever learn or understand anything, if he had not the faculty of perception; even when he thinks speculatively, he must have some mental picture with which to think." (32)

3. Canopus waterway enacted in the Roman garden at Emperor Hadrian's Villa in Tivoli near Rome.

In The Art of Memory, F.Yates describes the technique, which is a method that entirely depends on cultivated imagination used by the ancient Romans, who learned it from the Greeks. In this method the orator memorizes the component parts of a building, garden or a public place, in fact any habitable, architecturally clear space. The combination of the entire space and its distinct and memorable parts makes certain building complexes suitable for imagined, internal architecture in an orator's mind. The imagined spaces are the basis for the composed and easily assessable repositories, the loci, for the orator's remembered discourse. F. Yates describes the method of loci':

"Pausing for reflection at the end of rules for places I would say that what strikes me most about them is the astonishing visual precision which they imply. In Classically trained memory the space between the loci can be measured, the lighting of the loci is allowed for. Who is that man moving slowly in a vision of a forgotten social habit. Who is that man moving slowly in the lonely building, stopping at intervals with an intent face? He is a rhetoric student forming a set of loci." (8)

Once the setting is created and is rich in variety of architectural spaces within it, the orator goes through the place as if it is real and carefully places three-dimensional images, a number of objects or personages in a sequence of his discourse. Striking and emotionally charged images are placed in the imaginary architecture in a way that the orator can easily call upon them

4. Canopus Emperor Hadrian, 2nd Century AD. 5. Teatro Olimpico, Vicenza, Andrea Palladio.

This promenade, a stroll through cultivated imagined architecture, is the art and craft of skilled orators of antiquity. The images are often phantasmagorical: a maiden in a blue dress holding a lion with wings made of fire, a man in a red toga with deep green laurel wreath on his head and a large snake around his neck. These striking images will carry the essence, the gist of the paragraph or a section of a speech.

6. Approximating mnemonic images.

The Orator, by 'walking' through the imagined, well-ordered place, will unleash the issues held for him by the images he deposited into the architecture. In the classical Art of Memory, the imagination is the instrument for internalizing and retaining external facts. Some form of mnemonic process has been part of all oral traditions before the historically recorded Greek example of Simonides of Ceos and the collapsing banquet hall. Simonides, the only survivor, relied on remembered seating arrangements to call to mind the faces of recently deceased and disfigured guests

7. Approximating mnemonic images with renaissance and Baroque sculpture details.

The plasticity and abilities of the human brain to conjure images, harness or be guided by imagination, has been the wonder of sapient consciousness. This ability to recognize, retain and process imagery from collective and personal past, including the dreaming history, is perhaps also the faculty that allows for the comprehension and retention of things never seen or experienced before

Never seen before -Liverpool Inflatable 1969

8. Continuously, slowly moving inflatable sculptures.

S. D. Paich, the author of this paper, discusses in his earlier work Problem-Solving Models as a Unifying Principle of Creativity in Art and Science the phenomenon of unexpected connections and discovery:

In the complexities of the inner and outer world, the unexpected plays an important role. Often whole societies are structured to protect groups of people from the unexpected. But not all new things are threatening; the discovery of the wheel did not threaten the societies that found it—it improved them. (Paich 26)

The acceptance of newness is easier when the never seen before is attuned to the ascending qualities of imagination. That is, to a state prior to idealization, that fixes the beholding or anticipating of the new into a societal canon. When the new is too challenging, it evokes too much fear, and then the acceptance and enjoyment clash against a wall of communally-shared taboos. There is a paradox in the appreciation of contemporary art that it is regulated by now to be shocking and new. We now know what is ascertained as acceptable new, are works that look like art of early twentieth century Paris, or the New York Museum of Modern Art mid-twentieth century collection. In this constant renegotiating of what is acceptable new, there are works of art and imagination that, at the time of their creation, fell out of the modernity norm. The project cited here straddles the issues of: How new? Did its purposes generate the form? What was its identity? What memory residues did it leave behind? The project was a Large Inflatable Sculptures, installation/performance. Made from inflatable PVC with 12 dancers strapped with blowers; presented in 10 sites throughout the streets of Liverpool, England in 1969. This was one of the first inflatable sculptures created in Britain.

9. Liverpool inflatable sculptures, 1969.

The ambulatory project with a sculpture mounted on a track, moved every two weeks to another location in Liverpool during the summer of 1969. Twelve artists, dancers, actors, and volunteers animated them with household vacuum cleaners attached to their backs. Meanwhile, below the sculpture, stories were told, read, and enacted throughout the day.

The point of the inflatable sculpture and the track was for the project to temporarily infuse an unexpected meaning into the urban spaces it visited. The project was commissioned by the Great George's Community Cultural Centre in Liverpool Docks, England. What memory residues it left behind? A work of art, regardless if it has an immediate, discernable social context or is an expression in more general terms, that works opposite to the outreach or advertising practices of today. It is not what we need, as makers or grant-givers of the pieces, but what the individual audience members need to integrate, transform and cherish the experience. The remembering process could be called contra-propaganda, when the piece becomes a person's deep and idiosyncratic experience beyond the makers/artist/performers reach but encouraged by their work. The time, the place, and the people usually give a clue about where to begin to encourage the ownership of the felt experience as playfulness, not a surreptitious agenda. The sincerity of the subtext and appropriateness of the initial impulse, together with the form of the piece, become the containers for the future memory of the visceral experience. All the artist, helpers, teachers and volunteers who worked on the Liverpool Large Inflatable Sculptures were attuned to spot, discreetly celebrate and facilitate peoples' visceral experiences and enjoyment. In the case of expressive arts, it may be significant to observe, that the visceral and felt experiences of the audience, enable imaginative retention in their long-term memory, and form a cultivated richness to their life experiences. The acceptance and delight in newness, the never seen before aspect, may be one of the foods for nurturing the attunement of imagination as a living process.

Imaginative seclusion - Gardens of Villa Lante - in Bagnaia near Viterbo, 16th century AD

10. Gardens of Villa Lante looking up towards the water source.

Georgina Masson opens her pioneering classic study Italian Gardens with this remark:

It was no mere chance that a crystal spring chattering in the shade of an oak tree provided the inspiration for what is probably the best-known and loved lyric in the Latin language. The music of Horace's [65 BC—8 BC] Fons Bandusia holds a special magic for Mediterranean world whose scorching summer heat makes shade and water not only a favorite poetical theme, but also the necessary adjuncts of pleasure — especially pleasure garden, which since their earliest origins have in Italy always been associated with poetry and the arts. (Masson 11)

One of the finest examples of this notion of garden as a retreat not only from the heat of the summer days, but also haven of art, philosophy and the poetic imagination are the 16th century, Renaissance Gardens of Villa Lante in Bagnaia near Viterbo, Viterbo, 65 miles (105 km) north of Rome, is a local administrative center in the region of Lazio in central Italy. Lazio with Umbria and Tuscany was part of the lands of ancient pre-Roman Etruscan civilization. Viterbo was a medieval walled hill town that, after the fall of Roman Empire, was rising in importance. In the 12th and 13th centuries it attained real importance by becoming one of the favorite refuges for a politicized papacy.

Since the 13th century, Bagnaia had been the personal fiefdom of the bishops of Viterbo. The place, accessible, but off the beaten track, became the papal VIP retreat owned by the bishop as his personal grant for service. This complex interconnection of personal, public, political and poetic plays an important fact in the creation of this work of art. Lante, Montalto, Gambara are the names associated with the ownership of the garden. In the 17th century after having been the ecclesiastic property, the villa was sold to the Duke of Lante.

11. Gardens of Villa Lante, water staircase.

The Gardens and architecture of Villa Lante are the work of two bishops of Viterbo who succeeded each other: GianFrancesco Gambarra, a mature learned man who lived simply, and Alessandro Montalto, a cardinal at the age of seventeen and the nephew of Pope Sixtus V. The mixture of Gambarra, who had the taste and sophistication of a mature man, and Montalto, who had the enthusiasms and affinities of an adolescent, would produce one of the masterpieces of Italian Mannerist Gardens. The garden of Villa Lante is an inspired mixture of secular and sacred, natural and artificial, concrete and imaginary. Although designed by the men of the Church, the garden transcends a variety of contradictions into a meaningful playground of imagination.

The architect of the garden, Vignola, treated all of the buildings as garden ornaments. Vignola's inspired renaissance clarity and rational, worked organically with the imagination of one of the most inspired garden designers, architects and artists Pirro Ligorio, and with Thomaso Chiruchi, one of the greatest hydraulics designers in garden history. Together they created a magical space.

12. Descending water staircase and outdoor dining table with water feature for wine cooling.

For contemporary audiences, visitors and students, the old gardens are quaint places of play for the rich, now available to wider audiences through global travel. In their day they were the greatest experiments of the age, integrating science, technology, all of the arts and ancient mythology with religious and philosophical thought expressed as the garden's allegorical statuary, fountains, rooms and grottos.

The garden's story starts in the Grotto of the Deluge at the summit of the hill, from which the water is threaded throughout the garden in an unexpected and beguiling way. A Mytho-Visual story follows the poetic logic of the implied events while personifications awaken cultural references in the guest's imagination. The sculpture in the Grotto of the Deluge is of Pan, signifying raw, pristine nature coupled by the small temple of Artemis, and represents refined, cultivated wisdom. Together they open the story of the garden. The overall theme is based on the Roman poet Ovid's work Metamorphosis. Symbolically, the garden's allegories woven in statuary, water and architecture, enact the tale of humanity's descent from the Golden Age to the age the garden. In the middle of the descent, both of the water and the story, there is an outdoor dining area with a fountain table. Here in the imaginative seclusion of the garden of villa Lante, the 16th century masterpiece, the qualities cherished by the leading minds of the time were allowed to unfold. The garden guests had space and time for thinking, sharing, discussing, negotiating or individually enjoying and contemplating the intangible. It was neither a theater nor simply a flower garden, but a place for the interplay of imagination, cultural references and physical works of art. The allegorical intentions of this garden's makers, and embodied into real water, plant and carved stone, gave the imagination of the guests the necessary food to unfold naturally. Simon Schama in his book Landscape and Memory writes:

... fountains were conceived as stations en route to illumination, often connected by lines of water that mapped the progress of the visitor along a strictly predetermined and allegorically saturated path. That path was thus transformed in to a river road itself, navigated with the help of mythological and poetic references. At the Villa Lante at Bagnaia, built for the archbishop of Viterbo. (Schama 275)

In summary of this section, we could say that the subtexts and the stimulus that the allegorical statuary and place making provide, through representing intangible, is to bring into play the imagination. This flood of internal images is anchored and contained by the garden's elements and places, so that the garden dweller can integrate easily and effortlessly inner and outer experience and enjoy aspects of the boundaries, thresholds, overlaps and integration of art and imagination.

Persephone Myth staged in a swimming pool 2005

Spring Moon, the Persephone myth retold and enacted for the occasion of the reopening of the oldest public swimming pool in the North Beach district of San Francisco during 2005.

13. Stills from the performance Spring Moon, celebrating Persephone's return.

Seeing the figures of actors, dancers and musicians around a public swimming pool enacting an ancient story, was surprising enough. Seeing a swimming pool and water dressed as if actors, was the power of the piece. Nothing was what it is supposed to be, but dressed to draw and thrive on the power of the imagination of all assembled.

14. Glimpses of the scenic dressing of the pool.

In 2005, Artship Ensemble was invited by Friends of the DiMiaggio Park and Playground to create a piece for the reopening of a newly refurbished public pool in the North Beach district of San Francisco. The Ensemble responded with the staging of the Persephone Myth, enacted both in and out of water and at different edges of the pool.

15. Persephone honoring incubation in the dark and heralding new growth.

The commissioning group and Artship Ensemble were interested in creating a culturally significant work that was both an art and public commemoration piece, liberated from the clichés of public openings and yet being an element of one. The intention was to engage the imaginative, poetic side of the diverse neighborhood, give an unexpected but approachable performance, and mark the occasion with a memorable, once-in-a-lifetime event. Fabrics were the main staging elements for that purpose. Some of the fabrics had hundreds of ping - pong balls sewn into them by volunteers, affording floating scenic elements on the surface of the water. Other fabrics were allowed to trail from the edge, through shallow parts of the pool, all the way to the bottom of the deepest part. Some extremely large off-white silk fabrics were covering poolside furniture and objects. Although the top of the fabric was dry and sensitive to breezes and movement, the lower ends plummeted straight to the bottom with the water's weight. Hades performed at one end, surrounded with life-size sculptures of human figures covered with semi-transparent black synthetic silk. Clad in a generous black toga that was decorated with silver grommets, he beat a large dark drum. On the other end of the pool, in the Upper World of Persephone's mother, bits of color contrasted and harmonized with the general off-white of that area. The performance took place along three sides of the pool while the audience sat or stood at the larger fourth side.

16. Persephone reunited with childhood playmate.

The juxtaposition of modern pool architecture, the unexpected use of scenic fabrics, and the conscious use of color in the performance costumes, created an atmosphere which was very similar to images that manifest in the dreaming process.

After seeing the performance of Artship Ensemble's Persephone myth performed in the swimming pool, Dr. Paul A. Pangaro, a theoretician of conversation theory and cybernetics and a contributor to discussions on artificial intelligence, wrote about it this in a letter:

"my scientific training holds that our nervous system has as its fundamental purpose to maintain SYNCHRONIZATION with our environment. This started with pure physical survival, of course, but generalizes to language and culture. This encompasses evolution of all kinds. The homeostatic processes of the body are synecdoche, so to speak, for our living together in the world" (Pangaro 1)

17. Elements of the performance Spring Moon.

D. W. Winnicott articulates a response in his writing on the transitional object and transitional space:

The place where cultural experience is located is in the potential space between the individual and the environment. The same can be said of playing. Cultural experience begins with creative living first manifested as play. (Winnicott 96-97)

In another place he says:

It is in the space between inner and outer world, which is also the space between peopleéthe transitional spaceéthat intimate relationships and creativity occur. (Winnicott: 98-99)

The reason the Gardens of Villa Lante is paired with the Swimming Pool Performance is the re-interpreting mythological and ancient material and centrality of water as a binding and a surprise element of the overall design. Would a cultivation of art and multidisciplinary literacy help deepen the response and understanding of the needs and function of culture making?

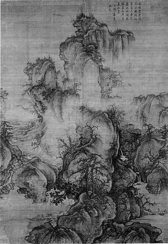

Leaving poetic empty space -Guo Xi (c. 1020éc. 1090)

18. Guo Xi - Early Spring.

During the Northern Sung dynasty, Guo Xi, pronounced: Kuo His, was a landscape painter who was the embodiment of the exceptional qualities required from a courtier in China at that particular time. He was versed in literature, calligraphy and likely a connoisseur of music in addition to all the refinements of courtly life. Expectations of rigor and excellence can be seen in the civil service examinations of the day which required the candidate not only to know literature but to be able to compose original writing within the canons of accepted standards. Expectations for a courtier were even greater. As a painter, Guo Xi probes the depths of perception and acute observation of the natural and human made environments. His understanding of the visual representation of scale (the relationship of infinitely large and infinitely small) as well as technical innovation were matched by his understanding of the psychology of invocation and the inner workings of imagination. His ability to conjure and share intangible experiences can be seen in his most famous painting Early Spring, made in 1072. The painting is a living embodiment of Guo Xi's principle of "the angle of totality," a technique sometimes referred to as "Floating Perspective."

This different naming of the same thing is important for us today. Guo Xi understood the totality of image not only as picture on a wall but what it does to a spectator attuned to it. Guo Xi's paintings are significant examples of the unique ability of art to communicate the essence and expose relationships in the visible world in greater totality than any particular isolated incident by itself. The communication of the sublime in the ordinary can often be conveyed in the painted representation better than in the mundane aspect of an incident itself. That may be why we are moved by contemporary photographs that help us see a unique angle or feeling of the portrayal away from its triviality, towards some elusive angle of totality while speaking directly to human, sapient sensibilities.

Perspective

Nineteenth and twentieth century art history have been based on an evolutionary model of progress from cave paintings to the art of the "civilized world". Renaissance perspective in its own day had a symbolic underpinning that after the 18th century became emblematic of rational western, "enlightened" and logical systems. Most introductory general education curriculums of art history only included Chinese painting to show how well-meaning but naive, even primitive, Chinese paintings were compared to the mathematical clarity of renaissance perspective. Hence this probably resulted in renaming angle of totality to floating perspective. This misconception has hindered western ability to comprehend and understand the immense depth and poetry of compositions like Guo Xi's Early Spring. Renaissance perspective in the hands of Botticelli, Leonardo, Durer, Rembrandt, Vermeer was never a dogmatic or pedantic system, but a basis to compose with and deviate from, so as to express a poetic intention and comprehension. In the hand of Guo Xi, the perspective becomes a notational system of imaginative evocations and not literal reproduction of facts. Deep understanding of the mobility of vision where the physical eye roams constantly and can see several perspectives all the time, is a starting point to guide, beguile, lead and re-tune the spectator over the surfaces of the painting which never feels like a flat surface but rather a glimpse of an aspect of the world. Just like Mozart's music leads us through many emotions and implied audio scenarios within each movement of a symphony, Guo Xi leads us through a visual score of a painted landscape.

The treaties and technique

Guo Xi developed a system that offered conceptual and practical guidance to the painters. His influences were far reaching. The quotes below from the Comments on Landscape Painting, translated by Shio Sakanashi, illustrate his thinking:

It is considered judgment of mankind that there are landscapes in which one can travel, landscapes which can be gazed upon, landscapes in which one may ramble, and landscapes in which one my dwell. (Sakanashi 32)

His treaties, equally address the painters as well as the "beholders", the connoisseurs, and the audiences of works of art. They attend to the prepared, cultured public that can lose themselves in the work of art and make it their own through internalized experience that ultimately can conjure the work in the inner eye.

Therefore, the painters should work with this in mind, and beholders should study the painting with the same idea. This is what is meant by not losing sight of the fundamental idea. (33)

The audience of his time appreciated the evocative literature using images of nature to express human feelings in the medium of calligraphy mounted and displayed as if it was a work of visual art rather then literature. From a cultural standpoint, Gui Xi writes:

Learning to paint is not different from learning to write. ( 33)

Guo Xi used light ink in layers and washes to model, modulate, dematerialize or solidify the forms. His technique was deeply concerned with a quality of aliveness in the spectator's experience. He knew something about arousing, beguiling and saturating the viewer and he worked on creating images where the spectator's spirit and aliveness could roam. In his treatise he says:

Narrow specialization has from ancient times been an evil. It is like harping on one note or playing on one string... As experience testifies, man's eyes and ears take delight in what is new and dislike what is old [monotonous]. This is world over, and that is I believe that great man and the virtuoso do not limit themselves to one school. (33)

Guo Xi knew the necessity of the internal mirroring of the outer reality as a prerequisite of sincere expression. He points to the essential distilling function of the imagination in his writing:

To learn to paint landscape, too, the method is the same. An artist should identify himself with the landscape and watch it until its significance is revealed to him. (35)

He can take us on a magic journey through his paintings almost effortlessly by guiding our eye and moving gently the gaze because he has been there, struggled with it deeply, digested his identification with the phenomena he portrayed so the spectator is gliding on his achievement. It is only when a foreign, external phenomenon has been fully internalized and its strangeness has been suffered through, that an artist can draw on the internalized images and create work like Early Spring.

Description of some aspects in the painting

Starting from the axiom of arts: that the whole [image, symphony, film, novel] is greater than any [lists, statistics or description] of its parts. This short account of the same physical qualities here, helps us appreciate the interplay of intention, artfulness and the imagination. To approach this description we are using a simple investigative folding technique so that the painting is not drowned in words and data hard to imagine, but rather aiming for an experiential approach and brevity of the text.

1. Vertical fold in the middle

19. Guo Xi - Early Spring analysis.

The central device of the painting's order is an S curve undulating organically around the invisible middle axis. The curve swoops in a strong bold base expressed through boulders and comes closer and closer to the axis in a cunning way to actually finish on it in its final turn. Although disappearing in the mist-ridden middle and above middle, it is strongly present in its visible and implied parts.

3. Horizontal middle fold

This fold reveals that the implied horizon is hovering around the geometric middle of the painting. Both the horizon and the middle are artfully digested but are present both in the open view on the left and the closer foothills on the right. This fold also reveals that the geometric, invisible center of the painting is in the mist and right above it is a tangible, emotional center of the painting where strong foreground disappears in the mist, then re-emerges to the roaming eye towards the summit. Placing the emotional center above the geometric middle is one of devices that pulls the eye upwards.

20. Guo Xi - Early Spring analysis.

3. Nine horizontal folds

These folds reveal that the layering of the ascending visual narrative and subtle ordering of the open lighter left and the more closed and darker right, have elements that are both at similar scale and at similar angle of gaze, and thereby preserve the poetic unity that transcends the one point perspective.

21. Guo Xi - Early Spring analysis.

4. Six horizontal folds

The spine, the integrating backbone of the images, is hidden in this simple division. The smaller number of vertical partitions adds to the openness and legibility of the painting. Not a single rule or concept dominates the composition. All of them are in service of the intangible communication offered by the work that gets meaningfully and deeply reconstructed in the mind and imagination of the spectator.

22. Guo Xi - Early Spring analysis.

Imagination

The visual score of the Guo Xi's painting Early Spring is more than what it represents. It is a seductive piece leading to implied transcendence. The work imaginatively avoids portraying the obvious or insisting on any detail as more important than the complex totality of the composition. The main aim seems to be an imaginative, internal journey that the painting evokes in the spectator. Just like the eye roams exploring the physical reality of things, so does the imagination move, flooding human consciousness with images and scenarios to give meaning to the observed phenomenon and accumulated facts. Vague, unstructured ink washes and fluid, even nebulous brush strokes are used to render surfaces that suggest mist, fog and other characteristics of the atmosphere. Once internalized, this atmosphere enters the imagination more than the moist air but as a symbol of the connection to the personal and deepest yearnings expressed through the culturally shared symbols like Tao and the Void.

Sustaining a void

Exploring the relationship of painting and the concepts of Tao and the Void, Michael Sullivan in his book Symbols of Eternity - The Art of Landscape Painting in China, writes:

Kuo His[Gui Xi] for all his literary tastes, seems to have carried still further the decorative bravura in the handling of ink wash that he had derived from Li CH'eing, who had painted his mountains "as if they were clouds." We do not often think of chiaroscuro as an element of Chinese painting, but Kuo His was master of it. (Sullivan 5)

M. Sullivan, also writes:

The landscape was not just a symbol of the Tao, it was the very substance of the Tao itself. As the fourth-century poet Sun Ch'o put it in his fu " Wandering on Mount T'ien-t'ai" : The Great Void, vast and wide, that knows no boundaries sets in cycle the mysterious Being, So-of-itself; melting, it forms the rivers and waterways, thickening, it turns into Mountains and hills [...] And, we might add, vaporizing, it becomes mists and clouds, the visible ch'I, or breath of living nature. The Buddhist shared all these Taoist feelings. (5)Through the process of hiding and revealing, the presence of the universal unknown emerged as a living, integral part of Guo Xi paintings. Through developing and orchestrating those seemingly vague, unstructured ink washes, he delivered them with both fluid or decisive brush strokes and succeeded in rendering surfaces that not only suggest mist, fog and other characteristics of the atmosphere, but the presence of the Great Void. This presence is the integral part of the work ----it is in what you see and what has been left out.

The process of hiding and revealing has an important place for human sensibilities and is of great cultural significance. Fashion, body covering, tribal markings, ethnic clothing are all examples of esthetic elaborations for the continuity of species and arousal of feeling and closeness. The stylization of the body is integral part of the courting rituals, a way to both awaken and contain the most primal desires.

These desires are not only for the continuity of biology, progeny, and the species, but also for the continuity of the elusive cognitive and symbolizing elements—the very elements that characterize the existence of language and consciousness. The enduring need for, and power of, music, painting, poetry and other arts, energizes the fertility both of imagination and biology.

The symbol and sign-making faculty of humans are possible responses to a primal need for the creation of a shared, tangible—but also transcendent—space of cultural experience. This need for continuity of all the aspects of human existence—the body and the yearning soul— manifest as culture. In return, the culture contains aspirations, drives, and the finest expressions.

The interplay of elusive, symbolic and real in Guo Xi's painting, Early Spring is an example of this reciprocity. The void he creates in his painting has a palpable, visceral, almost ritual quality --- an animation of the unknown. This type of communicable animism needs empty space.

Vertical Sculptures

22. Sculptural Poles Project USA, 1986-1991.

This project consisted of a great number of semi-permanent sculptures built for and with residents of the Golden Gate neighborhood in North Oakland by Slobodan Dan Paich and many local residents over five year period.

The sculptures ascend vertically, never too thick to begin with, while the forms rise and insinuate growth and let the air and sky enter them. These are poetic totems, as if messengers from other worlds, filling the urban void of sameness, grayness and decay. Intricately made, they also celebrate work, workmanship and working together.

23. Sculptural Poles Project USA, 1986-1991.

The project was specially conceived for an inner city neighborhood, of low to medium income households interspersed with homes owned by young professionals and some live work spaces, with a rich mixture of African American, White, Asian and Latino populations.

The project started in the garden of a house in the Golden Gate neighborhood that Slobodan was renting. He began constructing a temporary vertical sculpture out of scrap wood in his garden in front of the house. Curious children from the neighborhood came to watch, and soon they were working on the construction with him. Once the first pole sculpture was completed, one neighboring family asked for a pole installation on their property, and then neighbors across the street did the same.

Lottie Rose, Slobodan's landlady at that time, liked the sculptures and invited Slobodan to make several for properties she owned in the neighborhood. She offered a shed and outdoor work space in the parking lot of a building [she owned] on San Pablo Avenue, a busy commercial street in Oakland, and therefore an area that is when and where the project started in earnest.

Every Saturday for five years Slobodan was involved in constructing the vertical sculptures, assisted by people from the neighborhood, including the future owners of the sculptures. After having sculptures installed on their own properties, some of the neighbors continued to help with installations for other neighboring properties. Quietly, over the five-year life of the project, a great number of people participated.

The sculptures were given to the community free of charge. In addition to providing free space to assemble and stage the work, Lottie Rose donated the paint, brushes, nails, hardware, and even the ribbons. People from the community brought wooden scraps all the time, and later on some local businesses made in-kind donations of materials. In 1989, the City of Oakland recognized the project with a "Community Promotion Grant" award.

24. Sculptural Poles Project USA, 1986-1991.

The Sculptural Score

To give the project visual continuity and identity, it seemed appropriate to keep on in the same vein as the initial sculptures that were installed. Those sculptures were constructed entirely from wooden elements, most of which were recycled materials. The sculptures were an accumulation of diverse pieces into pinnacles of no more than six inches in diameter, and 15 to 16 feet high that tapered upward into lighter, sometime with open forms at the top. The sculptures often included heavily white-painted, thickened and saturated cloth, crocheted -pieces and other found materials. The vertical sculptural forms were punctuated by the distinctive and colorful elements of ribbons flowing out of the sculptural forms, animating the static elements. The all-white color of the surface was the simplest means of unifying disparate elements and catching the play of light and shadow.

Each time we tried to do something different from this basic score, the sculptural quality and the communication of the forms were lost. When we tried to paint the sculptures entirely black or brown, they became camouflaged and their immediacy and presence were lost. When we painted them red, green or yellow they lost sculptural quality as shadows became indistinct and unremarkable. When we tried to paint just one or a few of the elements, that also broke and diluted the form. When we added larger, more recognizable household elements, they made the sculptures appear cluttered and junky. When we added beautiful, specially embroidered, painted or silk-screened fabrics, they wrapped themselves around the sculptures in the wind and smothered them, so that neither the sculptures nor the materials were recognizable. In the end we returned to the basic sculptural score that emerged through the simple acts of people 'doing and making' together at the outset of the project. It seems that play of shadows and texture made visible in white on white and their otherworldliness was the cause of the success of their presence in the community. They were clearly products of and for imagination.

This process was an interesting dynamic in asking, more than answering, questions:

- What is the artist's role and what does she or he do in a community setting?

- How do the artistic sensibilities, vision and cohesive visual language remain while the creative process is shared with community?

We found, of course, that there is no set formula, and that each project has its own matrix and score. The one thing that remains clear is that if artistic concept, shaping and curatorial skills are not there, the project drifts from art in to another sphere which, of itself, is not a bad thing.

In the case of "Vertical Sculptural Poles," the project hovers at this edge of art and community building. The Vertical Sculptural Poles Project was a co-winner of the "Regenerating America" competition. The announcement read as follows:

Jeff Berkowitz judged the Regenerating America contest at the Celebration of Innovation Conference in San Francisco, selecting two winners. 'Slobodan Dan Paich and Mieilli's Products have both invented outstanding regenerative technologies,' said Berkowitz. 'Paich's is social invention and Mielli's is a material technology é both of which are essential to building a regenerative future. Paich's invention is a "flagpole" made from discarded products. The flagpoles are distributed throughout the community and decorated by each household. This invention builds community spirit providing an opportunity for individual creative expression. (Berkowitz 1)

The intangibles of the Vertical Sculptures

Vertical Sculptures engaged in a creation of a shared, tangibleébut also discreetly ritualized, symbolic space of a communal experience. It is an offbeat expression of the symbol and sign-making faculty and desires. In this instance the interplay of elusive, symbolic and real is contained by bland urban neutrality of the medium and low-income inner city. Symbolizing and dematerializing aspects are the reason the vertical sculptures are pared with Guo Xi's work. The palpable, visceral, almost ritual quality in Guo Xi's painting, Early Spring is an animation of the unknown. This unknown that needs empty space, has the same discrete similarity with Vertical Sculptures. The empty space for the Vertical Sculptures was the urban clatter that creates reciprocity of known, practical and the unknown poetic.

25. Constructing Sculptural Poles, 1986-1991.

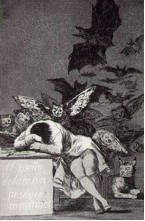

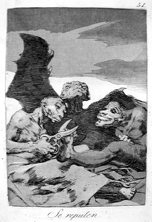

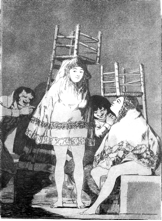

Francisco De Goya

Why writing about Goya in this discourse on Art and Imagination? Imagination is sometimes acquainted with daydreaming and an escape from reality. Bad dreams, nightmares, foreboding and fearful imaginings are considered a mistake, a shameful fall from angelic standards. This popular division of bad and good dreams has hindered the understanding of the organic need for fantasy and imagination. Goya confronts the dark side of human existence with unparalleled skills and sincerity. The mastery of and years needed to develop drawing dexterity, the capacity to cultivate and bear the inner promptings from the imagination and the ability to share them, are rare. Goya is an example of that type of artist.

Francisco De Goya was born in the mid 18th century in Fuendetodos, a village in northern Spain and moved to Saragossa with his family. At 14 he was apprenticed to Jose Luzan, a local painter. The fact that his father worked as a gilder and had seen and probably worked on a number of religious and secular works, and possibly used some form of drawing for his practice should not be underestimated. One must not forget that rococo frames were the most elaborate and fantastical creations. This background gave Goya so much support and recognition, he was sent to Italy to study and perfect his art. This may be a similar situation as when Picasso's father, who was an art teacher, saved all his life so Picasso could go to Paris and start his studio.

The impact of an educational journey to Italy cannot be overlooked in the development of outer taste, perception and connection to history as well as affording a profound set of cultural experiences that potentially help an artist in cultivating an informed link to imagination. Rome of the 18th century was the artistic and cultural capital of Europe. Every person of discernment and cultural sensitivity who was aspiring, established or famous in their own country, went to Italy and Rome as a crowning glory of their completed education.

Rome abounded in private studios and public academies that taught drawing and produced draftsman of great virtuosity. The fact that most participants had an earlier experience of drawing made these schools places of master classes. It was understood, since the Florentine Renaissance of the 14th and 15th centuries, that drawing was the basis of all the visual arts. Goya was one of the enthusiastic, lusty and eager to learn visitors.

26. Winter, tapestry prototype.

On return from Italy, Goya was asked to paint the famous tapestry cartoons. In the last twenty years of the 18th century, Goya painted designs for the royal tapestry factory in Madrid. His open, loose, spontaneous painting technique is partially due to the study of the works of Velazquez in the royal collection in Madrid. This daily practice of loose painting style created a set of specific mastery for portraying scenes from everyday life, and later in his carrier it facilitated rendering of social as well as fantastical and nightmarish imaginings with relative speed and authenticity.

In our world of the 20th and 21st centuries, a talent and passion like Goya's may have produced a great film director similar to Kubrick or Fellini. His is a master of sensing, interpreting and portraying everyday life. His patrons and admirers felt that he was giving them a unique perception and mirror of life, away from rococo and classicist idealization and themes. He could paint life just a little bit larger than life and hit the nerve and the sensibilities of his audience and time.

27. Truth Has Died- Goya's late work.

It is important to point out Goya's ability to straddle between naturalism, the discreet and spontaneous, and idealization with personal, poetic expressiveness. In his painted tapestry prototype Winter, created for the Madrid Royal Tapestry Factory, all these elements come to life. Every element is shown without excessive or obsessive detail. The quickness of gesture and an instinct to know when to stop, opens the painting to the spectator's imagination. As we observed with the work of Gui Xi earlier, in this meeting of imaginations of creating and evoking with observing and recreating, the real séance of art happens. Just as our body recognizes the elements of figures, so we feel viscerally the personages presented, so do the internal psychological organs of imagining respond to an imaginative, poetic trigger. In this interplay of imaginations Goya's Magic is experienced. This type of imaginative conductivity may be at the root of art's appeal to human sensibility. In the dark paintings and etching of Goya we follow his concerns, engagements and care for the human condition.

Goya gave visual voice to societal shortcomings and cruelties while envisioning and advocating for a freer world, a world of constitutional and civil governments. In his Caprichos published in 1799, he pioneered a more modern expression of social comment that combined with dream like scenarios of deeply personal nature. He was not making propaganda or illustrating the issues, he felt them and suffered them deeply. Their somber poetry is born from this courage to live with the demons of one's mind and the world. The world's reaction to this opus was controversial. Goya's admirers at the end of his life and particularly since his death saw him as a prophet, later as a proto-twentieth century artist. Art critics of his time and immediately after his death, who aligned themselves with established keepers of social stability and advocated subject matter of a more repressed and dignified nature, were disturbed by Goya's imagination and honesty, courage and skills to portray them.

Holland, V., GOYA - a pictorial biography. Thames and Hudson, London 1961 wrote:

[Los Desastres de la Guerra] These follow logically on Los Caprichis, in that they lay bare the horrors of a great social evil. They are an appalling indictment of war, without any attempt at minimizing its miseries, ... (Holand 68)

Holland, V. continues:

A well-known contemporary English critic, Philips Gilbert Hamerton, voiced the indignation of those who took offence at the pictures. He said that they 'proved how Goya's mind grovelled in a hideous inferno of its own, a disgusting region, horrible without sublimity, shapeless as chaos, foul in colour and "forlorn of light", peopled by the vilest abortions that ever came from the brain of a sinner. He surrounded himself, I say, with those abominations, finding in them I know not devilish satisfaction, and rejoicing, in manner altogether incomprehensible to us, in the audacities of an art in perfect keeping with its revolting subjects ... (70)

The mastery of and years needed to develop drawing dexterity, the capacity to cultivate and bear the inner promptings from the imagination and the ability to share them, are rare. In contrast to a standpoint of looking at art history and art training from an established, often required contemporary academism of shock and disturbance, Goya represents not only a prototype of a contemporary artist but also one of the last skilled pre-modern artists who has a full range of coordination of inner and outer worlds with an idiosyncratic expression that is infinitely sharable with the spectators who deeply participate in the work through invoked imagination and empathy.

28. Mezzotints from Goya's late period.

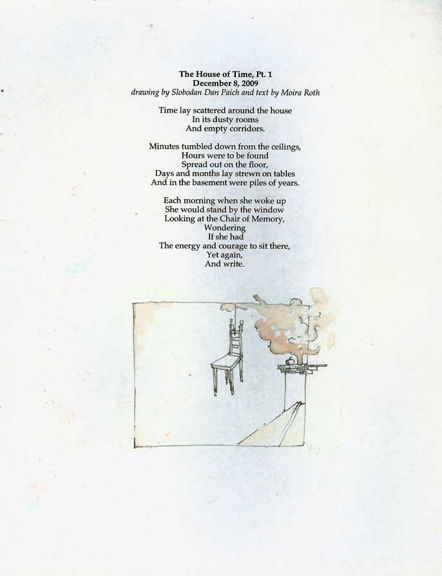

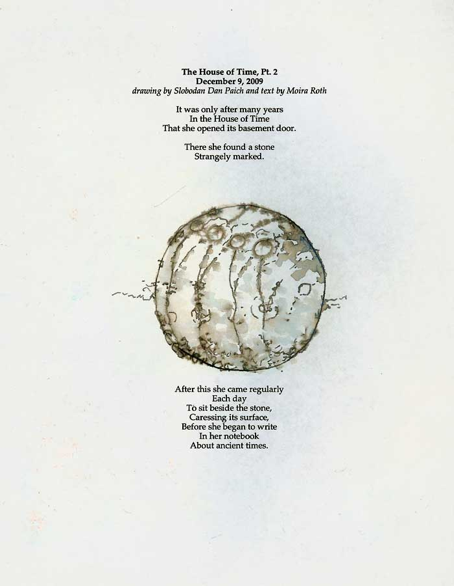

Dialog of two imaginations - M. Roth and S. D. Paich Exchanges 2008 — 2010

29. Drawings by S. D. Paich from the exchanges.

The reason the exchanges are pared with Goya's work is the inadvertent social comment by delicate work that does not fit within accepted modernity canons of its day full of de-contextualized information and over stimulation. It is a whisper among the shouts. A worldview that exists even when resources are limited, time is short and there is no space for a large work. Against all odds occasionally somebody finds energy to create new work. The pieces and the process shown here acts of defiance, when one continues to make things, make art, regardless of circumstances. This monumental effort sometimes creates miniatures as the bread sculptures of political prisoners testify.

For the past six years Slobodan always has carried a small sketchbook, a number of pens, brush pens with colored inks and one refillable brush pen with tea in it. He goes to a nearby teahouse after a day's work and makes small drawings. Often, immediately upon arriving home, he scans them and sends them to few very close friends. Frequently they provoke little statements or impromptu poems. One of the people in these exchanges, Moira Roth after writing, incorporates the image into her text, prints out a number of copies, and takes them to her local flower shop. The florists display them in the shop window. If clients of the shop like them, the store wraps them with flowers. This simple way of publishing and exhibiting is a discreet form of defiance through miniatures.

30. Drawings by S. D. Paich from the exchanges.

Moira Roth describing the exchanges wrote:

Paich sends me jpegs, always accompanied by poetic titles, of images--mostly drawings created that day (during his regular visits to a café near his home in San Francisco), but sometimes earlier ones (including photographs and painting fragments)--made in Serbia in the 1960s and later in England, 1967-1985. I quickly weave these into short narratives. Sometimes we give the image-texts as presents to friends, either sending them by email, or printing them out; other times, it is an exchange just between ourselves. (Roth 1)

Although the exchanges have bean presented in two sets of exhibitions in the last several years, they remain essentially an intimate exchange. The Library of Maps Exhibitions traveled to six locations during 2009 - 2011: San Francisco, Berkeley, Santa Cruz, Orange County, and Los Angeles in California and Poor Farm, Waupaca County, Wisconsin. The Library of Maps Exhibitions consist of poems by Moira Roth, drawings by Slobodan Dan Paich, photographs by Dennis Letbetter and broadsheets by Max Koch. In fact the last exhibition at Poor Farm in Wisconsin broke the intimacy spell as the work got entangled with the pressures, pretensions and ambitions of an emerging mainstream art center working its agendas vis-à-vis hierarchies of art success.

31. Drawings by S. D. Paich from the exchanges.

The exchanges shared in this paper [see appendix] were part of Once Upon and Now: Factual and Poetic Responses to History, 2010 and at The CounterPULSE gallery, San Francisco. The poems were directly triggered by the scans of the images. The exhibition wall label reads:

History as poetic source for the creation of new work has always been present in both Moira Roth's and Slobodan Dan Paich's work years before they meet. That quality of looking back to look forward is one of the elements of their exchanges. (wall label)

The scale, the process and the contradictions of public/private, make this project a discrete sample of the balancing act of art and imagination. Personal and shared, the exchanges are not an answer to any issues or questions of what is art, but yet another starting point that continues the ebb and flow of internal and external, a relationship of art and imagination.

32. Drawings by S. D. Paich from the exchanges.

Conclusion

By discreetly paring eight examples from the field of comparative history of art and ideas with contemporary art practices, a diachronic field of observation, reflection and critique was set to explore aspects of the inter-dependence of imaginative function and art and artifacts. To insure both the critical stance and the depth of experience, the examples chosen and paired off are from projects carried out from 1969 to 2010 by the author of this paper, as well as the author's research and teaching since 1969 in the field of History of Art and Ideas. This methodology of reflecting on doing and making from a standpoint of diversity of historic sensibilities and basing reflection and critique of history from art practice experiences, may illuminate the issues and ask questions in a new way. In other words the intention is to offer a broad context for the inquiry by looking at history from a doing and making point of view and reflecting on art practice with an historic perspective. The broad aim of this discourse is explore how these sets of skills and experiences may aid reflection on the relationship of external material culture and internal mental processes.

We started with the notion by Aristotle, that there is not a thought without imagination. Then the premise that the physical body continuously works to keep its equilibrium and adjusts processes for the physical survival. We cited and established examples of imagination almost as if a physiological organ. We observed the fact that the internal self produces images and nonverbal scenarios to help us deal with life's complexities. An example of this is the involuntary image making process that happens nightly in dreams. The relationship of memory and imagination as well as cultivated imagination vis-à-vis oral traditions, was touched upon. Finally, we analyzed and contextualized number of phantasmagorical examples from history of culture and the reflected on skills needed to make externalization of the imagined possible.

Two sets of open questions emerge as appropriate for the closure of this discourse.

The first set: What kind of inter-disciplinary expertise is needed for addressing the relationship of external and internal image making? We could name some: psychologists, artists of every discipline, anthropologists, art historians, neuroscientists, a hand full of professionals equipped in dealing with the process, mechanics and outcomes of imagination.

The second set: Does the ability to recognize, retain and process imagery from the collective and personal past, including the dreaming history, engage the same faculty that allows for the comprehension and retention of images never seen or experienced before?

Are the examples we cited [renaissance gardens, Chinese paintings, Goya's masterpieces, theater performances in swimming pools and trees] some of the ways of cultivating, and nourishing the audience's ability to integrate easily and effortlessly inner and outer experiences of art and imagination?

Are the rivers of images that abundantly and generously flow through the internal landscape of all sentient beings, the mediators of the relationship of external and internal worlds?

Bibliography

Borgeaud, Philippe. The Cult of Pan in Ancient Greece. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.

Lord, Albert. The Singers of Tales. Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1960.

Lee, Sherman E., Wen Fong. Streams and Mountains Without End - Northern Sung Handscroll and its significance in the History of Early Chinese Painting. Ascona: Artibus Asie, 1967.

Maeda Robert J. Two Sung Texts On Chinise Painting And the Landscape Style Of 11th and 12th Centuries. London: Garland Publishing Inc., 1978.

Masson, Georgina. Italian Gardens, London: Thames & Hudson, 1961.

Harris, Enriqueta. Goya. London: Phaidon Press Ltd., 1969.

Hsi, Kuo. Translator Shio Sakanashi. An Essay on Landscape Painting. London: John Murray, 1935.

Holland, Vyvyan. GOYA - a pictorial biography. London: Thames and Hudson, 1961.

Paich, Slobodan Dan. "Problem-Solving Models As A Unifying Principle Of Creativity In Art And Science" Art and Science Volume VI The International Institute For Advanced Studies In Systems Research and Cybernetics. (2008).

Rapelli, Paola. Goya. London: Dorling Kindersly, 1999.

Schama, Simon. Landscape and Memory. New York: Vintage Books, Random House, 1996.

Sullivan, Michael. Symbols of Eternity - The Art of Landscape Painting in China. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1979.

Symmons, Sarah. Goya. London: Phaidon Press Ltd., 1998.

Waldron, Ann. Francisco Goya. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1992.

Winnicott, Donald W. Playing and Reality. London: Tavistock/Routledge, 1999.

Winnicott, Donald W. The Location of Cultural Experience, International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, Vol. 48, Part 3 1967.

Winnicott, Donald W. Playing: Its Theoretical Status in the Clinical Situation. London: Tavistock Publications, 1971.

Appendicis

Appendix 1. The House of Time, Pt. 1.

Appendix 2. The House of Time, Pt. 2.

List of Illustrations

Note: All the images in this work are from the Artship Archives and were taken by Slobodan Dan Paich, unless otherwise noted.

1. Contemporary actors and storytellers are the keepers of oral delivery and mnemonics.

2. Rationale and order of architecture

3a./b. Canopus waterway enacted in the Roman garden at Emperor Hadrian's Villa in Tivoli near Rome.

4. Canopus Emperor Hadrian, 2nd Century AD.

5. Teatro Olimpico, Vicenza, Andrea Palladio.

6. Approximating mnemonic images.

7a/b. Approximating mnemonic images with Renaissance and Baroque sculpture details.

8a/b. Continuously, slowly moving inflatable sculptures.

9a/b/c/d. Liverpool inflatable sculptures,1969.

10. Gardens of Villa Lante looking up towards the water source.

11. Gardens of Villa Lante, water staircase.

12a/b. Descending water staircase and outdoor dining table with water feature for wine cooling.

13a/b. Stills from the performance Spring Moon, celebrating Persephone's return. Photos taken by Robert du Domaine.

14a/b. Glimpses of the scenic dressing of the pool. Photos taken by Robert du Domaine.

15a/b/c/d. Persephone honoring incubation in the dark and heralding new growth. Photos taken by Robert du Domaine.

16a/b/c/d. Persephone reunited with childhood playmate. Photos taken by Robert du Domaine.

17a/b/c. Elements of the performance Spring Moon. Photos taken by Robert du Domaine.

18. Guo Xi - Early Spring.

19. Guo Xi - Early Spring analysis.

20. Guo Xi - Early Spring analysis.

21. Guo Xi - Early Spring analysis.

22. Guo Xi - Early Spring analysis.

23a/b/c. Sculptural Poles Project USA, 1986-1991.

24a/b/c/d. Sculptural Poles Project USA, 1986-1991.

25. Sculptural Poles Project USA, 1986-1991.

26a/b/c/d/e/f. Constructing Sculptural Poles, 1986-1991.

27. Winter, tapestry prototype.

28. Truth Has Died - Goya's late work.

29a/b/c/d. Mezzotints from Goya's late period.

30a/b. Drawings by S. D. Paich from the exchanges.

31a/b. Drawings by S. D. Paich from the exchanges.

32a/b. Drawings by S. D. Paich from the exchanges.

33a/b. Drawings by S. D. Paich from the exchanges.

Appendix 1. The House of Time, Pt. 1.

Appendix 2. The House of Time, Pt. 2.