Slobodan Dan Paich Comparative Culture Papers

International Group for the Cultural Studies of the Body - CORPUS

Victor Bbabes University of Medicine and Pharmacy

International Symposium, Timişoara, Romania, 28-30, November 2011

Slobodan Dan Paich

Director and Principal Researcher

Artship Foundation, San Francisco

Learning Body–Feeling Mind

Cultural context and the role of dolls, puppets and models in child development

Abstract

Starting with inborn wisdom of the body - the infant reflexes. Continuing with an exploration of the cultures of carrying the baby and the internal and external space of child development as a field of mutual discovery and learning between a parent and a baby.

Exploring psychological aspects and neuro-development as part of the body, the paper reflects on ideas of D. W. Winnicott (1896-1971), pediatrician, child psychologist and author. He was a proponent of both the theory of transitional object of play as a healthy and necessary aspect of infant's development and also of the notion of the "good-enough mother." In our case of probing into aspects of an infant's relationship to anthropomorphic models, Winnicott's ideas may be helpful. His two concepts may aid our discussion: 1- the sense of self comes from the aliveness of the body tissues and the working of body functions, including the heart's action and breathing, the primary process regardless of external stimuli and 2- the role of transitional objects in the potential space between baby and mother, between child and family in a context of a img-fluiding social self, in response to the environment and external stimuli. By reviewing some of his views on weaning, transitional phenomenon and location of cultural experience, a general, open hypothesis of the paper develops.

Of particular interest is the non-verbal and proto-verbal potential of little figures - anthropomorphic simile for the child's early years of development of self and body. Exploring the cultural manifestations of the inner personifying function the paper looks into the archeological findings of toys and early models of the human body that include prehistoric votive figurines small enough to be held in hands. To bring out the issues of relationship of imagination to physical objects some observations based on archaic artifacts are interwoven with reflections on the phases of child development regardless of culture or time period.

Closing with an overview of papers, themes and disciplinary connections in the greater cultural context seeded by the presence and role of dolls, puppets and models. Tracing human representations may help articulate some open questions about the need for anthropomorphic recognition and reassurance.

Keywords: Child development, transitional object, personification, dolls and models, Cucuteni, Lepenski Vir, Willendorf

Starting with inborn wisdom of the body - the infant reflexes. Continuing with an exploration of the cultures of carrying the baby and the internal and external space of child development as a field of mutual discovery and learning between a parent and a baby.

Opening words

Learning Body - Feeding Mind is an open-ended discourse integrating actual infant development with related folkloric and archeological findings. A reflection on child development experiences, theories and observations may shed new light on surviving artifacts from ancient humanity. Also, this paper seeks to emancipate this early learning phase of all children across time as well as their parent's responses, as a legitimate part of the history of ideas and a cultural history of the complexities of a sapient, human body.

Inborn Wisdom of the Body

Reflex Actions are an involuntary, automatic and nearly instantaneous reaction to external stimuli. They may be considered defense mechanisms like a blink, sneeze or shiver that are a specific response to potential body harm. The fact that they happen without the conscious choice of an organism is important in understanding and valuing an inborn wisdom of the body. The constancy of Reflex Actions and its inter-species occurence offers potentially significant reference points in the cultural history of the body. For that reason calling them Primary instead of Primitive may help some alignment and cultural critique.

There are reflexes that a baby manifests from the first moment of being born that appear miraculous to the experienced or inexperienced parents. In child development theory and observation they are referred to as Infant Reflexesi. The involuntary readiness and consistency of these reflexes makes one of the first relational parent–child interplays. It is like a set of non-verbal vocabulary–reactions, each with it own characteristic. These involuntary reflexes originate in the central nervous system and are part of normal infants' responses to specific stimuli. Through typical child development the frontal lobes inhibits these reflexes so they do not manifest as a child img-fluids. We shall briefly describe a few as a foundation before approaching physiological and cultural thematic threads of this paper.

Infant Reflexes

The section is mostly based on two child development textbooks by Laura E. Berkii and on conversations by the author of this paper with mothers nursing their babes (2010–11) or remembering time with their infants. Because these reflexes are so universally present in the beginnings of every human being's life, this section hopes to evoke for the reader, beyond the factual narration, a form of recollection of the reflexes however non-existent or distant the memories are.

Deeply connected to survival is the Swimming Reflex. When an infant finds itself faced down in a large body of water, it will automaticaly begin to paddle and kick as if swimming. An atavistic involuntary reaction of the Swimming Reflex, is a stark reminder of survival traits of an infant. Although this instinct is not in the repertoire of playfulness with one's baby, it is part of the reactions that the newborn brings with it.

The Clinging reflex is typically present in all infants/newborns up to four or five months of age. The reflex is a response of an infant feeling that it is about to fall and has lost any support. It manifests as a baby's symmetrical movements of stretching the limbs outwardly and toward the midline of the body, often crying. When the infant loses its balance, the reflex helps to regain a hold on its mother's body, and embrace the mother. This seemingly physical balancing of a baby and working mother, traditionally carrying the baby on her body all day, has immense relational ramifications.

From birth a healthy child sucks at any object that is in contact with the roof of, the mouth. The Sucking Reflex, an iresistable, insatiable involuntary response is reassuring for both the mother and the child. As a mother experiences bodily that the child is equipped with necessary survival skill, she can open and adapt to her baby.

Also in the first month a baby's head will move toward anything that brushes its mouth and cheek. Through the Rooting Reflex the baby narrows the field of search by circling around the object until it finds it. Very quickly the baby learns to recognize the source of food and if breastfed goes to it directly, to a delight of a mother witnesing the learning and increased accuracy.

One of the most fascinating early manifastations of conecting and learning is the Grasp reflex. Through this action, the baby's fingers will tightly close and grasp anything that finds its way and strokes its palm. In principal the grip can support the weight of a new born. This instict offers the potential of playfulnes with the baby and safe mock survival gestures if and while securely held at the mothers body.

The fascination with the Walking/Stepping Reflex is one of the favortite ways people engage with a newborn up to and in the first month and a half. When the baby is held securely by an adult, with both of their hands under the baby's arms then placed on a flat and firm surface with the soles of the feet feeling it, an infant will automaticaly try walking with altenating steps. Although babies in the first month can not support their own weight, this foretelling of the future healthy child and adult endears the baby to the care givers and the family.

In this paragraph we shall touch upon a number of reflexes briefly to give them a space in the general discourse. The Foot Plantar Reflex manifests as toes curl down as if grabbing the ground or in the Swinging Reflex the baby will swing towards the side where the skin on the back is stroked. In Palm Presura Reflex the infants may open the mouth, bend or rotate the head when both palms are gently pressed. The Neck Reflex manifests when the head is turned to one side, the arm on that side will straighten while the other arm will bend. Some child development experts consider the neck reflex as a inborn aptitude that develops later as the hand/eye coordination of the infant. The Neck Reflex is also precurser of the infant's voluntary reaching.

Repetition of these movements as play and exercise are an important component of a mother being with her child. The child feels good because the mother is in an open and relational space exploring, marveling at her baby and she receives from a baby sense of well being. Even hurried or repressed mothers have moments with their infants where this relatedness is flowing. Although the list of Infant Reflexes is not large, it addresses many parts of the body and motor functions opening the primary nurturing to all intangible and cultural possibilites of the socialized being.

L. E. Berk in her book Infants, Children and Adolescentsiii present in the section titled Reflexes and early social relationships makes the following observations:

… the baby's sucking behavior is highly organized. Bursts of sucks are separated by pauses, a style of feeding that is unique to the human species. Some researchers believe that this burst-pause rhythm is an evolved behavior pattern that helps parents and infants establish satisfying interaction as soon as possible. This early sequence of interaction during feeding resembles the turn taking of human conversation. Using the primitive sucking reflex, the young baby participates as an active, cooperative partner.

The mutual learning and discovery of infants and mothers seems to be one of fundamental steps of continuation of humankind. Like so many natural phenomenon, it is always new with each instance within a biological framework.

The Cultures of Carrying the Baby

As the ever-present complexities enter different phases of mutual and self discovery, the physical closeness of a child and a mother in the early months and years, plays an important role. Many cultures have evolved simple baby carriers, large pieces of cloth, pouches and tailored or woven back strap containers. In the process of weaning and sometimes having to leave the infant for awhile, the reality of a working mother, being always bodily close to the baby is not realistic. Naturally or inadvertently, more and more the elements of separation and otherness enter. For the moment, we shall consider the phase where mother and child are close together physically and emotionally as the mutually experiential field of learning bodies.

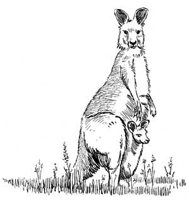

For the sake of comparative inter-species reflection on the way of carrying newborns, we briefly look at the Australian Kangaroo. Although the animal was not known to ancient and indigenous cultures, a few short paragraphs about Kangaroo's procreative and nurturing habits may bring in to focus the issues of close relationship of birth and postpartum baby carrying.

Kangaroo fetus only stays in the womb for approximately one month. The newborn is less than an inch and the half, below four centimeters long and is sightless, hairless almost like a little worm with four rudimentary limbs. The more developed future upper limbs are means for the newly emerged embryo to propel on the epic journey in to the mothers pouch. The assent happens through the mother's abdominal fur in less than five minutes. Once the newborn gets in to the pouch and finds one of the teats, it firmly attaches to and starts sucking.

In the pouch the newborn develops very fast, initially for a short while poking its head out of the pouch. The baby kangaroo img-fluids and develops for six months before fully emerging out of the pouch. The young kangaroo dwells more and more outside the pouch. To re-enter the infant uses sniffling of the pouch. After about eight month it leaves the pouch permanently.

The Kangaroo's front legs are not used for general walking/hoping, they have almost dexterity of the fingers allowing a mother to use them in the grooming process of her baby that creates contact and mutual bonding beyond the dynamics of the pouch.

The context of the special bonding and closeness of mothers and newborns are ubiquities across the species it is always a form of mutual body learning that includes an inquiring, hungry mind. To understand the role and the significance of the presence of dolls, puppets and models in children's early body awareness, we contextualize by looking at a number of systematically observed phenomenon, written documentary evidence by pediatricians and contemporary child development researchers and on non verbal traces in certain archeological and historic artifacts.

Contact in Spite of Difficult Birth

Pediatrician and child physiologist D. W. Winnicott in his book The Child, The Family and The Outside World writes with an intention of supporting new mothers and families of newborns. For that end he cites instances where after a difficult birth the mother has limited range in her initial handling of a baby:

Babies and mothers vary tremendously in their condition after the event of birth, and perhaps it will be two or three days in your case before you and your baby are both fit to enjoy each other’s company. But there is no real reason why you shouldn’t start to get to know each other right away, if you are well enough.

Out of his systematic observations and innumerable cases he chooses a specific example of a limited contact to illustrate that bonding and mutual learning have many forms. He describes a first time mother convalescing after a difficult birth yet making very early contact with her baby who was put in a cradle by her hospital bed:

For a while he would lie awake in the quiet of the room, and the mother would put down her hand to him; and before he was a week old he began to catch hold of her fingers and look up in her direction. This intimate relationship continued without interruption and developed, and I believe it has helped to lay the foundation for the child’s personality and for what we call his emotional development, and his capacity to withstand the frustrations and shocks that sooner or later came his way.

D. W. Winnicott advises a mother that is being helped by a nurse in a convalescing situation to have contact with the baby outside feeding hours:

… you are at a disadvantage if your baby is only handed to you at feed-times. You need nurse’s help, and you are not yet strong enough to top and tail the baby yourself. But if you do not know your sleeping baby, or your baby as he lies awake wandering, you must get a very funny impression of him when he is handed to you just for you to feed him. At this time he is a bundle of discontent, a human being to be sure, but one who has raging lions and tigers inside him. And he is almost certainly scared by his own feeling. If no one has explained all this to you, you may become scared too.

Here and in some other moments in his writing, D. W. Winnicott advises the new mother to know as many aspects of her infant as possible:

In between time he is only too glad to find mother behind the breast or bottle, and to find the room behind mother, and the world outside the room. Whereas there is a tremendous amount to learn about your baby during his feed-times, you will see that I am suggesting that there is even more to learn about him while he is in his bath, or lying in his cot, or when you are changing his napes.There are also difficult times when baby wants and does not want to nurse. D. W. Winnicott comments:

...sleep in your arms instead of working at his feed, or when he becomes agitated so that he is no good at his job. He is just afraid of his own feelings, and you can help him at this point as no one else can by your great patience, and by allowing play, by allowing him to mouth the nipple, perhaps to handle it; anything that the infant can let himself enjoy, till at last he gains the confidence to take the risk and suck.

Regular nursing hours and uninterrupted feeding are easier on a parent, while exploration, partial rejection of food and grabbing attention are baby’s way of probing and controlling with and from a small body. Interplay of control and boundaries begins to enter early into a mutual learning process and space. Babies discover beyond instinct and necessity, the power of crying and arousing mother from having her attention elsewhere. Wanting and not wanting to feed are dynamics where the characteristics of two inter-connected beings are mutually tested. These complex and delicate interactions are beginnings of otherness, of socialization.

Weaning

Like all processes surrounding the development of an infant, weaning has its innate instinctual side. Everyone involved somehow knows that breast-feeding will come to an end. Individual characteristics of a mother and child and social expectations enter the process producing variable timing, reactions and formative traits. The important and difficult feeling of closure and separation enter the field of learning and psychological development.

Winnicott has studied weaning both from the physical and psychological point of view, he writes:

But the breast-feeding experience carried through and terminated successfully is a good basis for life. It provides rich dreams, and makes people able to take risks.

Contextualizing further our interest in the dynamics and timing of infants' adoption of external objects and anthropomorphic simile, we turn to Winnicott for more insights into weaning as a way of emptying and creating space for new experiences and learning, he writes:

In the last chapter I described a baby who caught hold of a spoon. He took it, he mouthed it, he enjoyed having it to play with and then he dropped it. So the idea of the ending can come from the baby.

This hand and mouth exploration of the objects other than breast or bottle is an important learning phase, Winnicott continues:

It is plain that at seven, eight, or nine months a baby is beginning to be able to play games of throwing things away. It is a very important game, and it can even be exasperating because someone has to be all the time bringing back the things thrown down.

By nine months most babies are pretty clear about getting rid of things. They may even wean themselves.

In weaning, the aim really is to use the baby's developing ability to get rid of things, and to let the loss of the breast be not just simply a chance affair.

Winnicott advises the new mother about containing her infant awakened by hunger and frightened, regressed to wanting the breast as the only consoling solution and the need for the mother to see her baby through this phase. Even when the process is relatively peaceful Winnicott observes:

Or things may go well, but nevertheless you notice a change towards sadness in the child, a new note in the crying, perhaps going over into a musical note. This sadness is not necessarily bad. Don't just think sad babies need to be jogged up and down till they smile. They have something to be sad about, and sadness comes to an end if you wait.

Recognizing the need for contained natural sadness and deeper feelings is a first step towards reflective and cultural experiences, Winnicott continues:

So, there is a wider aspect of weaning – weaning is not only getting a baby to take other foods, or to use a cup, or to feed actively using the hands. It includes the gradual process of disillusionment, which is part of the parents' task.

Weaning as a process of individuation and emergence of selfhood is very important to our discourse. It is background for Winnicott's articulations of the transitional object.

Transitional Object

Studying infants evolving from complete dependence to gradual self-reliance, Winnicott observed a natural, transitional, intermediate developmental phase. This sequence is where the time of transition creates a new awareness for the baby, a new relational space between the inner psychological and outer, external reality. Regardless of geography and culture at this time of transition, the living outer space and the intimate space between the mother and the child acquire a new sense of mutual learning, broader sense of the inner and outer world for the baby and challenges of managing this dependence/independence.

From Winnicot's writing, we get a strong sense of transitional phenomena taking place in the transitional space that begins to include elements of the outside world entering between a mother and a child. In this space Winnicott observed and articulated the emergence and presence of the "transitional object."

Transitional object is a real object invested by the baby with deeply personal and relational meaning. It could be anything that is safe for baby to handle, a piece of string, a small blanket or piece of cloth, but often an anthropomorphic looking object that includes teddy bears. Non-tangible phenomenon also appears in the repertoire of repeatable personal transitional objects, like a word, a word like a incomprehensible utterance or a melody. The transitional object is the first possession of choice that belongs to the infant. The involving and multi-layered aspects of a transitional object open a child to the use of illusion, symbols and metaphoric thinking. These aspects get lost because some psychologist see transitional object only as a security device because one of its functions is to replace mother in her absence. Taking the transitional object when going to sleep is not only to ward of deep fears and insecurities but also to bring a cherished object to the inner world of dreaming.

Just as walking, swimming or grasping, instincts come with a newborn, and the weaning takes place naturally in most cases, so does the transitional phenomenon and its object. They belong to cognitive development and environmental adoption. The involuntary imagination of the dreaming process and the voluntary process of fantasy are deeply connected to the internal responses to the transitional object of an infant.

The exclusivity of one object being more precious than any other at that time, the transitional object has traits and internal responses to and outside, ‘non me', similar to the falling in love of older humans that facilitates species continuation.

The Location of Cultural Experience

The psychologist D. W. Winnicott, quoted in previous sections, is a significant contributor to play theory and has included ideas and observations about the cultural experience in relation to the transitional phenomenon. Winnicott describes cultural experience as an extension of the initial learning process and a necessary nexus for rich, sharable human experiences. In his The Location of Cultural Experience (1967), he writes:

The potential space between baby and mother, between child and family, between individual and society or the world, depends on experience which leads to trust. It can be looked upon as sacred to the individual in that it is here that the individual experiences creative living.IV

In his essay Playing: Its Theoretical Status in the Clinical Situation (1971), Winnicot states:

The place where cultural experience is located is in the potential space between the individual and the environment (originally the object). The same can be said of playing. Cultural experience begins with creative living first manifested as play.v

Winnicott's observations help place cultural experience as one of the central fields for deepening self-knowledge and cultivating the abilities of immersion and sharing.

Some contemporary schools of psychology overlook or take for granted two aspects of playing: intimacy and companionship. They articulate causes for playing as libidinal expressions, safety vehicles for aggression and anxiety releases. The author of this paper through his own research, observation and teaching agrees with Winnicott's understanding of the intimacy of play which connects the child with an innate quest for wholeness and finding one's place in the outside world, while keeping in touch with fantasy and the internal processes of image making. When this intimacy is shared with a companion or companions, a very rich interplay of fantasy and reality is contained by the actively of play. Similar experiential subtleties and richness happens between audiences and players, spectators and visual arts or readers and texts. Winnicot writes in The Location of Cultural Experience (1967):

I have used the term cultural experience as an extension of the idea of transitional phenomena and of play without being certain that I can define the word ‘culture'. The accent indeed is on experience. In using the word culture I am thinking of the inherited tradition. I am thinking of something that is in the common pool of humanity, into which individuals and groups of people may contribute, and from which we may all draw if we have somewhere to put what we find.

The diversity of the common pool of humanity although astonishing in its variety when observed globally or across time, shows some underlining commonality and traits. The explorations so far and the reflection triggered by Winnicott's ideas are intended to pave a way for probing later in our discourse into the phenomenon of anthropomorphic simile as children's learning and becoming tool and their inter-cultural commonality.

S. D. Paich, the author of this paper looks for these common traits in exploring the relationship of story and place in his work Genius Loci and Scenography (2007)iii. The traditional concept of genius loci, spirit of place, has a number of meanings ranging from the special atmosphere of a place, through human cultural responses to a place, to notions of the guardian spirit of a place. After describing the occurrences of place invested with their guardian spirit and associated with a myth, hearsay, and a story he develops ideas of common intentionality in the section titled Need For Stories.

The relationship of story and place may be opened by an idea that, in the archaic recesses of our being, we ward off unbearable levels of irrational anxiety through the need for, and the mechanisms of, personification. To personify is to represent things or abstractions as having a personal nature, embodied in personal qualities. Personifications are usually embodied in a place or scene set aside for communal gatherings: a place for a symbolic ritual or a performance. Personifications manifest in a form of statuary, ritual markings, buildings, gardens, processions, and ambulatory performances.

When personification acquires duration and begins to exist in time, a rudimentary story may begin. This embryonic story, an individual inkling, finds great relief in joining the established flow of existing stories and well-known myths. That may be why children love hearing old stories over and over again.

Although the word personification implies a human face or figure, the investment of natural and human-made objects and animals with certain qualities of soul or spirit, i.e., animism, are manifestations of the same process.

The phenomenon of Tarantism, the multi-faceted manifestation of illnesses and “moods†caused by the bites of the tarantula spider—and its cure through the dance of Tarantella—are living examples of the process of personification. In the ritualized interplay of affliction and recovery, a reintegration of the affected person into the community takes place through dance.

The positive side of this personifying, story-seeking function, is to give humans a sense of belonging, of community, and, to use Phillippe Borgeaud's term, recovered closenessvii. The negative side of the personifying process is investing others with our panic and creating chauvinism, racism, and similar manifestations.

Just like the physical body continuously works to keep body fluids moving, temperature almost constant, the stomach acid at manageable levels, etc., so does the psychological self produce compensating, relieving images and nonverbal scenarios, or proto-stories to help us deal with life's complexities.

The continuous interplay of panic and recovered closeness is central to family or community life; it never goes away. Just as babies need continuous reassurance and feeding, so do adults, but in sophisticated ways which reinsure them of implied communal bonds. The transitional objects of children or ancient votive figurines, with associated ceremonies share this bonding, reassuring and inter-relational characteristics.

Prehistoric Goddess Figures and Child Development

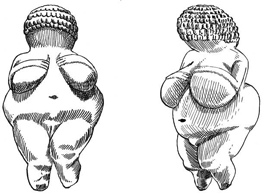

Through an exploration of the influence and presence of anthropomorphic simile in children's lives, we shall look briefly at the prehistoric goddess figures and surrounding culture of their production and veneration. Certain characteristics are ubiquitous to the majority of figurines from many geographic areas. They are small, easily held in a hand and often made of baked clay, easily curved limestone or bone and most probably by women.

For example, the abundance of the statuettes of well-rounded women in Maltese temple complexes links them to sanctuaries across the Mediterranean and to the watersheds of the Black Sea and Indian Ocean. The Venus Of Willendorf , 25, 000 BC is the best known example of this type a cult figure.

Thematically, Maltese goddess figurines are also linked to Africa by the discovery of the Venus of Tan-Tan in the Atlantic watershed of the river Draa in the vicinity of the town of Tan-Tan, Morocco. Venus of Tan-Tan is considered one of the oldest artifacts of the Stone Age found between two chronologically identifiable layers, one of 200,000 and the other 500,000 years old.

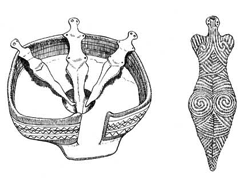

One culture that provides a glimpse of domestic life in pre-history is the Lepenski Vir on the Danube River.

At Leoenski Vir in each dwelling there is a rectangle hearth forming an axis to the open plan of the dwelling. This axis extends immediately with two other objects, the central altar of the place made of a carved river stone, and a flat stone slab used as a table on the ground for preparing food, eating on and making objects for daily use and symbolic practices. This main gathering focus of the dwelling is the place where mothers and children spend their time together. In view of what we explored earlier in the paper, the richness and the phases of interactions and mutual learning of mother and the child took place around fire, alter and the table. The underlining characteristics, inborn instincts and phases of child development and integration of an infant into the society, in essence may have changed little over millennia. The fact that small figurines representing woman were made in environments similar to the living arrangements at Lepenski Vir yet over large geographic areas, also points to the possibility that babies touched and played with this or specially dedicated figures. The whole cultural ambiance of these symbolic objects has an aura of prenatal and postnatal understanding, perceptions and values. Below is another alter found in Lelenski Vir carefully placed between the hearth and the table.

Lepenski Vir was inhabited from the Mesolithic to the Neolithic period for more than a millennium. At Lepenski Vir simple but sophisticated culture flourished between 5000 and 4000 BC with traces of human settlements since 7000 BC. Lepenski Vir district consists of one larger settlement with visible traces of intentional proto-urban planning and ten related villages situated on the banks of the Danube in Serbia, close to the Djerdap / Iron Gates gorge. This section of the Danube is shared between Rumania on the north bank and Serbia on the south. In prehistoric time this territory was part of the same culture shown in 2010 at an exhibition titled The Lost World of Old Europe—The Danube Valley 5000—3500 BC at Ashmolean Museum, Oxford University. This exhibition is dominated by examples of small figurines of woman from a number of sites along the Danube from Vin?a near Belgrade to the Black Sea Estuary. The figurine of a women or goddess mostly known as Venus of Willendorf also comes from the Danube Valley much further up the river in what is today Austria.

Held in Hand

The two disciplines taken together may shed light on each other and help open new understanding of what are characteristics of the common pool of humanity and links of biology and culture and culture and human continuity.

When we look at photographs of babies, not starving babies but infants from simple subsistence communities around the globe, we see healthy, alert children participating in life and relating to their surroundings from a very close physical proximity to their parents. Although the photographs show geographically and chronologically distant occurrences, remarkable similarities in infants' behavior and attitude are evident. Often exhibiting what Winnicot describes as a sense of self that comes from the aliveness of the body tissues and the working of body functions, including the heart's action and breathing, which he refers to as the primacy process regardless of external stimuli. When we look at archeological remains of the dwellings at Lepenski Vir, it is easy to reconstruct and imagine the aliveness and functioning of prehistoric children similar to our own or from indigenous communities anywhere else in the world.

When we look at artifacts from Cucuteni, Lepenski Vir, Malta or Willendorf it is not hard to imagine the presence of figurines in the prehistoric child 's surroundings and hands. Again, if we turn to Winnicott's articulations about the img-fluiding social self in response to the environment and external stimuli, the location and img-fluidth of the cultural self can be easily reconstructed. Namely the dynamics and learning that happens in the prehistoric social structures and its rich cultural context that Winnicott calls the common pool of humanity. In the end, the modalities and variants of an underlining common experience start with what babies explore with their mouths, hands and minds around parents' bodies and the familiar space, as well as the objects, stories and rituals that infants witness and integrate.

Anthropomorphic Simile

Marco Fitta in his book Games and Toys of Antiquityviii dedicates a section to the dolls of the ancient world. One of the images chosen is a well-preserved cloth doll from Egypt of the Roman period now in the British Museum in Londonix. These kinds of soft anthropomorphic models for use by children may have a long tradition. Textiles as organic material disintegrate and the toys found in Ancient Egyptian royal tombs are more stately, made of more durable materials and suitable for older children. Nevertheless this beautiful Roman example points to specific doll making for children. The cloth dolls are easier to manage in the phase when a baby needs to throw things away and a more precious votive object may have bean experienced under parental supervision. M. Fitta analyzes his examples as gender biased with a view that dolls are for girls. Which in the examples of terracotta and wood he cited from the Roman period is justifiably based on evidence. The little cloth doll on the other hand resembles votive figures of earlier, possibly matriarchal periods. When we look at some of the elegant figures from the Cucuteni and Danube Valley we find also both genders represented in an overwhelming majority of female figures. An extremely open hypothesis emerges that in the matriarchal society that very young girls and boys have played with transitional object in human form regardless of gender. In a number of Islamic traditional societies boys go with their mothers to public bathhouses until a certain age as they are regarded as being infants and not having strong gender identity. B. S Hewlett in his book Intimate Fathers—The Nature and Context of Aka Pygmy Parental Infant Carex presents culture where fathers spend half of their waking time with their babies. Hewlett in his anthropological studies demonstrates the difference between infant care and the gradual introduction of boys to secrets and dangers of the forest. The universal needs of all children for recognition and reassurance are helped naturally by everyone and everything involved.

Final Words

Based on the elements we cited so far and not to over elaborate a summary of key characteristics and associated ideas of little figures—anthropomorphic simile is offered:

Small enough to be handled

It can not be overestimated the role of an intimate object that can be handled not only for the development of motor hand to brain co-ordination

but also for the development of discernment, choice and what will become aesthetic sense.

Inner and outer reality

The models of the human body that are small enough to be handled are the focus, junction of the flow from inner world to outer reality and development of

the ability to know and distinguish between them is as important a body function as breathing or digestion.

Personification

The investment of models with human characteristic, so naturally and universally adopted by children is an extension and expression of the personifying

instinct and its psychological function. Starting with doll's name, a rudimentary sense of its character and with imagined or real changes of cloth are the

beginnings of what for example in the img-fluidn-up world of the phenomenon theater would represent and nurture.

Non-verbal

Some elements of a doll's presence in an infant's life are visual and tactile reassurances and pretend nurturing that happens, offering something

even smaller than a child to be looked after. Also complete or partial survival of the doll after the child's tinkering or anger, helps develop

understanding and practice of the return of closeness, something tangible to cherish and hold.

Phantasmagorical and fantasized

The natural internal processes of dreaming, unbearable anxiety, sweet imaginings and conflicts of needs and wants have a receptacle in the humanly shaped

model that will absorb and stimulate the imagination.

Seeming magical

Like all aspects of playing and make-believe that appear real, ritualized and cunningly available to respond to infants emotional needs

are in a way talismanic and magic in their appearance to the child.

Understanding the body

In the end however rudimentary the —anthropomorphic simile offers an inventory of the body with placement and names of the parts. The little

models help practice, explore, assimilate and integrate language and experience.

Transitional object for exiting at the other end of life

We may understand the enormity of early transitional phenomenon and models of human body with a brief look at the other end of an

individual's existence and in to an object designed to help transition from this life to no life or life somewhere but not here. Examples

are numerous: Ancient Egyptian Pyramids and Royal Tombs, sculptures showing Buddha in transcendent tranquility or Jesus in agony on the cross. For cultures

that shun visual representation of the human body we find chant, hymns and songs communicable to human sensibilities. The abstraction of gardens of raked

sand and a few rocks absent of human figures are not without a human resonance. The expressions of essential traits for the necessities of transitional

signifiers are as diverse as humanity.

In closing we can say that the intricacies, individual idiosyncrasies and the cultural differences may obscure the need and general pattern associated with models of human bodies that children could hold and touch. The overwhelming presence and usage across time, geography and civilizations makes the little figures the forbears of the cultural life of the future adult.

i L. E. Berk, Infants, Children and Adolescents

ii L. E. Berk, Infants, Children and Adolescents

iii L. E. Berk, Child development

iv D W Winnicott, The Location of Cultural Experience, International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, Vol. 48, Part 3 1967, p. 4

v D W Winnicott, Playing: Its Theoretical Status in the Clinical Situation, Tavistock Publications, London 1971, p. 2

vi S. D. Paich, Scenography and Genius Loci, invited paper for Scenography International Prague Quadrenniale Research Conference 2007

vii Philippe Borgeaud, The Cult of Pan in Ancient Greece, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.

viii M. Fitta, Giochi E Giocattoli Nell'antichita. Leonardo Arte, Milan1997. p. 56 & 57

ix Cloth doll from Egypt, Roman period, British Museum, London. p, 57

From: M. Fitta, Giochi e Giocattoli Nell'Antichita, Milano, Leonardo Arte s.r.l, 1997, p. 57

x B. S. Hewlett, Intimate Fathers–The Nature and Context of Aka Pygmy Parental Infant Care. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor 1991

Bibliography

Berk, L. E., Infants, Children and Adolescents, Allyn and Bacon, Boston 1999, p. 150-153

Berk, L. E., Child Development,Allyn and Bacon, Boston 2006, p. 126-128

Borgeaud, P., The Cult of Pan in Ancient Greece, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.

Fitta, M., Giochi E Giocattoli Nell'antichita, Leonardo Arte, Milan1997. Pgs 56 & 57

Hewlett, B. S., Intimate Fathers – The Nature and Context of Aka Pygmy Parental Infant Care.

University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor 1991

S. D. Paich, Scenography and Genius Loci, invited paper for Scenography International Prague Quadrenniale Research Conference 2007

Winnicott, D. W., The Location of Cultural Experience, International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, Vol. 48, Part 3 1967, p. 4

D W Winnicott, Playing: Its Theoretical Status in the Clinical Situation, Tavistock Publications, London 1971, p. 2

Winnicott, D. W., The Location of Cultural Experience, International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, Vol. 48, Part 3 1967. p. 4