Slobodan Dan Paich Comparative Culture Papers

Presented University of Sibiu, Romania, September 19-23, 2013

Director and Principal Researcher

Artship Foundation, San Francisco, USA

Caves Echoes, Archaic Polyphonic Singing and Harmony of Spheres Traditions

Abstract

In opening we briefly look at archaic, ancient and Greco-Roman music traditions as examples of cumulative societal interactions leading to defined cultures and as expressions of shared fields of experiences, values, mores, taboos and aspirations in the territories of Mediterranean and Black Sea watersheds

Early signs of intentional sound making can be potentially traced to the echoes and overtones found in prehistoric cave. Traditionally looking for traces of prehistoric music was an archeological impossibility. Recent research emerged and focused on cave paintings and markings made by ancient humans signaling the places of significant acoustic phenomenon. An example of acoustic archeology is the work of I. Reznikoff (2004) at the Pech Merle caves in southern France. This paper posits possible connection between acoustic cave notation and an almost extinct archaic polyphonic singing tradition. When we turn to other disciplines and systematic study of oral traditions, something of cave resonances may appear. We find rare versions of a related, specific type of archaic polyphonic singing surviving in Corsica, Sardinia, Sicily, Albania and Istria in the Mediterranean Basin and Bulgaria, Romania, Georgia and Anatolia in the Black Sea Watersheds.

Human made acoustic phenomenon of overtones at the Hypogeum, the Paleolithic temple on Malta, points to intentional sonic ritual spaces refining and celebrating the natural possibilities of tonal ranges. At Hypogeum, the Oracle Chamber adjacent to the central circular Sanctuary is acoustically tuned to the human voice and produces not only an echo but also overtones to specific notes, which attest to the sophistication and knowledge of the builders and users of the sanctuary. The Oracle Chamber, particularly the ceiling, is decorated with spirals and circular nodes in red ochre. Were they a notation, a score of some kind?

Unexpected notations of audible and inaudible sounds in the symbols of Pythagoras and Plato point to music traditions of the pre classical world. The fact that Pythagoras at the age of twenty went to the temple schools of Ancient Egypt and was trained there before returning to Greek Territory at the age of forty, opens this paper's interest in the nature of gathered, composed sound and its transmission. Pythagoras is considered one of the fathers of western mathematics and music theory. He had declared that the planets and stars made an inaudible music, a 'harmony of the spheres.' A century later Plato absorbed this tradition and embedded it in his dialog Republic. Using Stichometry, science historian J. B. Kennedy (2010) "reveals that Plato used a regular pattern of symbols, inherited from the ancient followers of Pythagoras, to give his books a musical structure." The paper briefly looks at the continuity of Pythagorean music theory through Classical Antiquity and Middle Ages.

In Closing we consider examples of three folk songs' rich cultural expressions and sound structure and conclude with a brief exploration of human biological, emotional and cognitive need for organized sound and shared sonorities.

Part I

Introduction-Archaic Notions

The concept and word archaic in modern language use is associated with antiquated, bygone, obsolete, old-fashioned and the outmoded. It is not often used in its broader sense as vitality, relevance, continuity and inherited meaning. Like the word primitive, archaic could also be related to primordial, original, formative. From the child development point of view the archaic sound is related to auditory experience in the womb and early developments of the brain whereas the Cerebellum of adults holds some basic function and is often referred as a primitive, atavistic brain. In that sense archaic is always present biologically. Culturally some of the most sophisticated images of animals from prehistoric art are referred to and classified as primitive.

I. Reznicoff, a great musicologist, anthropologist and pioneer in exploring the possible acoustic intention of prehistoric painted caves through using the sound of human voice in his paper On Primitive Elements Of Musical Meaning [1] writes:

The deep primitive sound level is always present in our consciousness (in the corresponding areas of the brain) and because of its primitiveness [primordial biological continuity] it remains unaffected even when other, more superficial levels of consciousness are damaged or destroyed, by accident, illness, stressful situations or age. 2.4

I. Reznikoff continues in the same section of his paper with:

[...] the very first levels acquired in early childhood and even before birth. With the exception of the sense of sight, the means of perception, particularly the auditory system, of the child in its mother's womb are already formed at the sixth month of pregnancy. [...] It is also important to notice that the first consciousness of space is given by sound. The child doesn't see but hears the voice of the mother high or low in her and the sounds or noises in various locations coming from internal or external surroundings. This sense of space is important for the child to position itself in the right way, head down, in preparation for the moment of birth. It has been shown that children whose mothers sing are in general better positioned for this major event. 2.4

I. Reznikoff in his studies makes a relationship between prenatal and early childhood experiences of hearing and prehistoric cave echoes and singing of ancient humans. He forwards an important hypothesis concerning the practice and meaning of archaic music and its relationship to painted markings, image and possible societal function that are explored later in the paper.

Cumulative societal interactions

Issues of ubiquitous personifications found in human response to natural phenomenon may help contextualize the intentions of this paper and give some broader cultural sense of shared motives and practices of similar underlying intent manifesting in different forms throughout the ancient world. S.D. Paich, the author of this paper addressed Personification in his paper Scenography and Genius Loci-Reinvesting Public Space with Mytho-Sculptural Elements for Performance (2007) [2]. Here are integrated some aspects of that text.

In the archaic recesses of our being we ward off unbearable levels of irrational anxiety through the need for, and the mechanisms of, personification. To personify is to represent things or abstractions as having a personal nature, embodied in personal qualities. Personifications are usually present in a place or scene set aside for communal gatherings: a place for a symbolic ritual or a performance. Personifications manifest in the form of statuary, ritual markings, votive or apotropaic paintings, buildings, processions, ambulatory performances and stations on the roads or crossroads.

When personification acquires duration and begins to exist in time, a rudimentary story may begin. This embryonic story, an individual inkling, finds great relief in joining the established flow of existing stories and well-known myths. That may be why children love hearing old stories over and over again.

Although the word personification implies a human face or figure, the investment of natural and human-made objects and animals with certain qualities of soul or spirit, i.e., animism, are manifestations of the same process.

Just as the physical body continuously works to keep body fluids moving, temperature almost constant, the stomach acid at manageable levels, etc., so does the psychological self produce compensating, relieving images and nonverbal scenarios, or proto-stories to help us deal with life's complexities.

The continuous interplay of panic and recovered closeness is central to family or community life; it never goes away. Just as babies need continuous reassurance and feeding, so do adults, but in sophisticated ways which reassure them of implied communal bonds.

Although it is outside of sound phenomenon, the example in the following excerpt contextualizes and contributes to the understanding of archaic behavior and sophistication of ancient humans. In J. & C. Bord's seminal study of water lore in British Islands titled Sacred Waters [3], observe that over a quarter of the examples occurred near bridges:

That our ancestors regarded water-crossings as places where one required protection from supernatural forces is evident in the discovery of the archaic stone carved head motif on many bridges. The image of the head possessed an apotropaic function in many pre-modern cultures,

J. & C. Bord continue by observing widespread beliefs associated with water crossings regarded as zones out of the ordinary both as potential portals to the unknown and openings for unwanted visitations:

[...] the potency of water itself was frequently anthropomorphized into elemental figures. The bridge or ford was not just a boundary in space in the same manner as gateways or crossroads; water itself was fundamentally supernatural. The traveller on the crossing would be beset by the Otherworld on all sides and hence such places presented profound spiritual as well as physical danger.

Parallel to archeological remains and found artifacts, the intangible issues of Sacred Waters, like the use of sounds in this discourse are probing pointers to expressions of shared fields of experiences, values, mores, taboos and aspirations that, through cumulative societal interactions, lead to defined cultures.

Cave Echoes and Intentional Sound Making

To reflect on this possible relationship of archaic singing to specific places we turn to Professor S. Errede from the Department of Physics, The University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign, in his article Pre-Historic Music and Art in Paleolithic Caves [4] he writes:

Recent acoustic experiments carried out in some of the caves in southwestern France under the direction of Iégor Reznikoff have shown that in the majority of such caves, the presence of wall paintings and drawings is highly correlated with the phenomenon of natural echo at that location in the cave, and especially so at particular resonant frequencies. Furthermore, it has been established that indications relating to the nature of the particularly resonant sound are recorded not in the form of some kind of random graffiti, dispersed at the whim of the prehistoric artist, but instead as precisely-coded signs within the pictorial representation, often explicitly indicated by means of lines or dots emerging from the mouth of a person or animal drawn, in precisely those areas of the cave where the echo is most pronounced. (pg.9)

S. Errede in the same paper shows the photograph, taken near the entrance, just inside the Pech Merle cave in France. On the ceiling of the cave are red dots placed there by prehistoric people to indicate a zone of special acoustic significance—resonances. Other photographs in the paper show some of the prehistoric drawings of animals and other figures that had been made at various locations on the walls of the Grotto du Pech Mer as a potential prehistoric score. [5]

The reason we are quoting the paper by Professor S. Errede from the Department of Physics of the University of Illinois who describes the work of I. Reznikoff, is the fact that it is the physics department not the archeology or music department that recognize I. Reznikoff's work. Is it not that physics in the last fifty years is confirming notions of physical reality corresponding to models of molecular galactic relationship articulated by ancient people in forms of myth, songs and communal sharing? Often an interdisciplinary exchange creates a breakthrough in spite of prevailing currents and specialisms. An example being the case we shall discuss later about stychometric analyses, usually used in connection to organic chemistry that was applied to Plato's Republic revealing a hidden music score.

The other observable phenomenon worth note and study is the effects of cave soundings on human nervous system in the wake of challenging ninetieth and twentieth century views of humans as animals or machines, particularly in psychiatric research. Early humans were in touch with the need for sapient conciseness and natural brain and body development. The invisible a priori bias of animal-machine paradigms implies objectivity to experiments that denied cultural and communal characteristics of human society and needs. I. Reznikoff's research and life work brings us close to observing those archaic reactions, somewhat forgotten, to the inner and outer reality through the human body. I. Reznikoff writes:

A modern ear is no longer trained to sense the fine differences in ancient intervals or those of oral traditions; while the comparative meaning of these intervals, at least for some of them, is clear and has an objective base. Mastering these intervals, one shares with certain musicians of learned spiritual non-European oral traditions the ability of making people cry or go into deep states of interiority (it is much easier to make them joyful: usually a lively rhythm would do). 2.7

The artificial, commercial, insistently upbeat, unnaturally loud and mechanistic ubiquitous electronic disco music of our day is a testament of how far the delicate sound landscape has gone or been lost. I. Reznikoff observes:

In a prehistoric cave, one of the most impressive experiences is to discover the cave, walking in complete or almost complete darkness, and all while making sounds (preferably vocal ones) and to listen to the answer of the cave. In order to figure out where the sounds come from—from far away or from nearby-and whether there is somewhere a strong resonance or not: all this in order to ascertain the direction in which one may proceed further on. 2.5

I. Reznikoff describes his experiment in the caves where vision is limited by darkness, in his methodology of evoking resonance by singing a few simple tones as the only way to anticipate how long or deep the space ahead is.

This represents one use of the voice and of the hearing as a sonar device, and there is no doubt that Paleolithic tribes who visited and decorated the caves proceeded in this way; indeed, in irregular shaped galleries or tunnels, neither oil lamps nor even torches light [battery operated] further than a few meters. This sonar method works: in many cases, proceeding into the direction of the strongest answer of the cave will lead to the locations of paintings. 2.5

This sophisticated means of positioning a painting at the auspicious spot signals profound understanding by the ancient humans about the intricate relation between diverse elements and participation in them through sapient sensibilities and worship. I. Reznikoff continues:

This way of moving around in darkness demonstrates the main importance of sound in discovering space and in proceeding through it; to be sure, it reminds one of the first perception of space the child has in the world of the mother's womb. 2.5

I. Reznikoff's research led him through unusual, awkward and narrow caverns, where he had to crawl, searching for the maximum resonance of specific cave spaces, which when activated, affected the entire human body while progressing in the dark. He describes himself crawling and making vocal sounds, when suddenly the whole section of the cave began to resonate. Then he wrote in his research findings that after he put the light of his lamp on, red dots were there on the wall of that specific resonant part of the cave. While observing the relationship between humanly generated sound and cave space with the red dots on walls and ceilings, it became evident to him that the wall paintings representing different animals in these special acoustic places also contained markings for sound. I. Reznikoff describes how he began to imitate in certain cases the specific painted animals represented that created optimum resonance for some of the space. As anthropologist and musicologist, I. Reznikoff's keen observations and methodology was aided by remarkable skill sets of being also a practiced singer with deep baritone/base and student of overtone singing and toning of Siberia where imitation of animal sounds is part of the repertoire. I. Reznikoff continues in his paper:

Since all sounds can be, potentially, related to vocal or corporal sounds and since, as we have seen, vocal sounds, namely vowels and consonants are related to different parts of the body, we see that all sounds are related to our body. The evidence of this major fact demanded a clear demonstration. It sheds a new light on the question of the meaning of music. 2.8

This is where the universe of sound comes alive, intersecting in the human body and generating sense of meaning. The ancient humans took the lessons of cave resonances and their master singers who activated them and brought the experience to communities, places of worship, mythic worldviews and early thinking about the natural world and places of aliveness of sound in it.

Archaic polyphonic singing

In several previous papers reflecting on the presence of Mediterranean polyphonic traditions expressed in tonalities different from the tempered scale of western music since eighteenth century AD and different from the Pythagorean-Ancient Egyptian music modalities of classical periods closer to our time, S.D. Paich the author of this paper sketched a series of open hypotheses about archaic polyphonic singing [6]. This type of singing survived in the Central Mediterranean Basin, the Balkans and the Black Sea Watersheds. The following text is a synthesis, reiteration along with some verbatim sections from S.D. Paich's earlier cultural history papers and lecture notes.

Corsica, Sardinia, Albania, Istria

In remote parts of Corsica songs celebrating Mary, mother of Jesus were sung in churches in an archaic three part polyphony. The remote regions of Corsica were only accessible by dirt roads and mule tracks well into the mid twentieth century. The regions preserved the archaic polyphonic singing transmitted by oral tradition over centuries and were only recorded by musicologist in the 70's of the 20th century. These field recordings became the basis for a subsequent revival and integration of archaic polyphonic singing into Corsican mainstream popular music and the emergent national identity. This type of polyphonic music is essentially different from parallel religious or popular music based on a tempered scale. The difference lies not only in tonalities and procedural characteristics but also in the particular devotional intimacy of unaccompanied, orally trained singing. The singers have often img-fluidn up and trained together.

In Corsica, polyphonic singing is typically in three parts. It consists of a special contrapuntal relationship between the two upper parts supported by the base. It is intimate polyphony, traditionally sung by male singers, each part sung with special competences. These competences presume the religious nature of singing that provokes a particular set of emotions, deeper than conventionalized piety. [This is not a critique of piety but a diachronic reflection on cultural continuity and similarities across the Mediterranean. A comparison drawn from observing the poetic quality found in devotional music in many cultures]. In analyzing the performance dynamic of archaic polyphonic music we may reflect on possible reasons for the permanence of certain forms of expression over long periods of time. The three parts Corsican archaic polyphony [7] adopted itself to Christian liturgical evocations of sacred mother. The three parts are called a sigonda, a terza and bassu:

A Sigonda is a part of the singing tradition where the lead singer sets the tone. By lifting the voice his role is not unlike muezzin's call to prayer. A Sigonda singer is both the lonely human voice imploring an audience from the un-knowable forces of nature and representative of an individual in a community. The depths and beauty of his imploring is shared and understood by his community. Men and women identify with the call.

A Terza is a poetic, stylized representation of the presence of another human being, answering, contributing to the call, a co- aspirant. The two are soaring together, modeling a sense of solidarity within the boundary of transparent, recognizable local tradition. A Terza singer gives to the audience or rather to his community by singing an embellishing counterpoint to the lead singer, a tradition handed down for centuries. The familiar embellishments offer a reconciling quality similar to myth and heroic epics. Everyone knows the story but they are reassured each time, by the resolution at the end. The role of A Terza singer is also like a humanized, stylized echo from a special sanctuary cave.

Bassu is the grounding, harmonic function of lowest voice. The ancients knew about the evocative quality and the paradox of a deep voice. It is on one hand reassuring deeply grounding, while on the other hand it has a quality of implied universality. We are purposefully careful in using terminology to describe the intangible here, as we want to stay in the realm of observable phenomenon. Neurologists and musicologists have observed the soothing effect of the deep tones on the human nervous system. The liturgical singing of the Byzantine Rite and particularly the Russian Orthodox choral work utilizes this dual function of the deep bass voice.

As we point throughout this paper, the versions of this specific type of archaic polyphonic singing can be found in several places around Mediterranean, Balkans and Caucasus.

Polyphonic singing of Sardinia

Very similar to Corsica, Sardinian Canto a tenore survived and flourished in the more remote and pastoral culture of central Sardinia.

While Corsican is three part devotional singing, Sardinian polyphonic chanting is performed with four distinct vocal parts by four men standing in a circle very close together. The four distinct parts are boghe the narrator, the lead voice, cronta or contra a dialoging voice, mesa boghe or mesuvoche the harmonizing partner of contra and the consolidating echo of the lead and basso the grounding and transcending base. With its deep timbre the Sardinian base has an identical function as Corsican bassu. Although sometime bassu is the narrator as well, the general attitude, function in the community and division of singing parts is clearly part of the same archaic musical tradition.

The tenores polyphonic chants have an overall quality of a lament, both in secular or ceremonial settings. This may be because this music tradition is based in the devotional singing. The Sardinian polyphonic chant's sacred songs are called Gozos.

The Sardinian A Tenore singing style [8] was recognized, in November 2005, as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.

Albanian Archaic Iso-Polyphony

Also recognized as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.

Albania is another Mediterranean mountain region with strong pastoral tradition and survival of an archaic form of singing the Iso-Polyphony, resembling Sardinian and Corsican examples.

"Iso" is the name for the drone accompanying the singing. The drone can be continuous or rhythmic depending on the region. Like Corsican or Sardinian polyphony it is generally sung by male singers. Today in the concert halls or on television the lead singers are also women. For thousands of years in pre-industrial societies, the Iso-polyphony where a family tradition transmitted from parents to children, similar to the transmission of traditional crafts, trades and folklore in general.

The recording Albania | Labe County—Complaints and Love Songs is a remarkable document of the majority of the different types of Iso-Polyphony. In the accompanying notes to the compact disk B. Lortat-Jacob and V Sharra write:

With regard to polyphonic music, such practices belong to a shared communal heritage that obliges each to take an active part and set out to move all those assembled. The Albanian music on this recording should be seen and heard in this context. When fully mastered, this singing has a penetrating occult force, a magic. In performance, its singers do far more than simply apply the rules of a relatively straightforward musical grammar of notes and melodic formulas memorized by their ancestors; their music is a song that they actually do enjoy "being together" evoking in an extraordinarily effective way the charm of solidarity. The performance has in fact as much to do with ethical concerns as with aesthetic ones. For in the process of strictly oral tradition, singing is a collective moral responsibility to work out a sound from in the close company of a select group of friends.

This text and the title of the recording Complaints and Love Songs points to the deep societal function of these songs.

Istrian polyphonic tradition and music scale

Istria, in Croatia is the largest peninsula in the Adriatic Sea and the most northern point of the Mediterranean. It is a home of a distinctive musical form, a style of two-part polyphonic singing. Usually performed by male singers who sing "thinly" and "thickly," with a consolidating pulse on the lowest note and the final resolution.

In Istria this type of song is also sung by women, or in the combination of a male and a female voice or by a male voice accompanied by a small shepherd's pipe.

Like in Corsican, Sardinian and Albanian archaic singing, in Istria too, there is a lead singer performing the narration melody within the usual range of a male voice. The second singer also follows the embellishing, dialog role we found in the earlier examples. In Istria the second singer accomplishes that in the "thin" form of traditional singing, in the high register, that is also characteristic of some echoes. "Thin" denotes the high, "thick" the low register of the voice. In some cases the lead singers return to the deepest notes as expressed as a rhythm, the narration's cadence. It is the most rudimentary expression of the reassuring quality of the deep notes similar to more elaborate bassu singers from the mid-Mediterranean islands. In Istria the role of the singer performing "thinly" is sometimes taken over by a small "flute," sopela that plays the counter part of the dialog and embellishment.

In the notes on Isatrian music accompanying field recording from the archives of Radio-Televizije Beograd, S. Zlatić [10] writes:

The music represents the archaic bottom layer, which has not undergone either temporal or territorial influences. One does not feel here the influence of the neighboring musical folklore areas or the influence of art music. However the most recent tunes—and they are still being created do use scales based on the tempered musical system, and thus lose the archaic qualities.

Musicologists studying this archaic bottom layer of music in Istria and nearby geographic areas of the Croatian coast have identified a recognizable five-tone musical scale different from the Pythagorean and Egyptian pentatonic scale we still use today. In the musicological archives of Dr. Milica Ilijin (1910-1992), an early mentor of the author of this paper, are several pages of music notation with notes from experts trying to define the intervals of the Istrian scale writing intervals in percentages next to the notes. These intervals are beyond half or quarter tones of the pentatonic or octave scale as we know them. This unusual sonorities provoke a question: Is the origin of this tonality possibly in natural echoes and overtones of certain sacred spaces codified and carried home for soothing, communal connection and evocation of the Paleolithic sensibilities of the transcendent?

The stone hand axe about 2 million to 800,000 years old was found in the Å andalja Cave near Pula, Administrative center of Istria, Croatia. Marking the human presence in Istria in the Lower Paleolithic. In the Upper Paleolithic there are numerous findings of human presence from 10,000 to 40,000 BC, exemplified by large deposits of bones of hunted animals. The Neolithic period yielded discoveries of pottery, other artifacts with traces of husbandry and agriculture.

This archeological findings of material culture bring us to consider other traces of human presence in ancient caves. As we mentioned in the earlier chapter, the article Pre-Historic Music and Art in Paleolithic Caves, by Professor S. Errede honors the life work of Iégor Reznikoff recognizing intentionality of cave markings and their relationship to human singing may point in a direction. By reflecting on this relationship of archaic singing to specific places, this paper proceeds by positing possible connection between acoustic cave notation and an almost extinct archaic polyphonic singing tradition.

When we turn from archeology to other disciplines and the systematic study of oral traditions, something of sophisticated archaic usage of sound emerged. A shared pattern is discernable from studying comparatively rare versions of a related, specific type of archaic polyphonic singing surviving in Corsica, Sardinia, Sicily, Albania and Istria. The rich territorial variations within this type of singing but also similarities of intention, style and expression, point to a cultural phenomenon shared among people of considerable geographic area.

In the next chapter we explore the intentional building of Paleolithic temples that respond to specific tones and echoes activated by human voice integrating the sonic caves experiences with a dedicated place of worship, these monumental tectonic achievements with accompanying acoustic shaping may be also integrated into archaic tonal influences.

Hypogeum

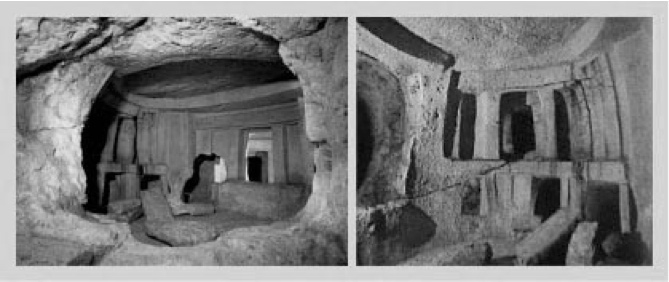

In Paola on the island of Malta lies the unique temple complex known as the Hypogeum of Hal-Saflieni. It is a rare prehistoric underground temple on three levels, and the best known in the world.

1. Holy of Holies, the inner-sanctum at Hypogeum at Hal Saflieni

The Main Chamber, hewn out of rock, is circular, in a similar esthetic to the curvilinear temples above ground. Using the typical megalithic three stone structure the trilithon-two vertical posts supporting a horizontal lintel-in the Hypogeum that arrangement is represented by the way the rocks are curved. Although some parts of the underground sanctuary have freestanding stone construction, it is the effect of monumental architecture carved out the living rock that gives the Hypogeum its unique, intended experiential quality. In this Main Chamber the statuette of the sleeping lady was found.

2. Sleeping Lady or Goddess found in the inner-sanctum at Hypogeum at Hal Saflieni

In the paper The Subterranean Sanctuary at Hal Saflieni [11] co-authors S. Mifsud, A. Mifsud, C. Savona Ventura revisit the observations about the Maltase underground Temple Hypogeum from an array of scholars that include the carefully considered findings of the first director of the National Museum of Archeology in Valletta, Themistocles Zammit (1864—1935). T. Zammit was the original systematic researcher of the Hypogeum after it was re-discovered accidentally in 1903. One of the main thrusts of the paper was the reflection on the intended function of the Hypogeum. The authors state in their summary of the paper "The traditional funerary role of the site is challenged in favor of its primary function as a subterranean 'megalithic' temple or sanctuary."

The authors point to the fact that the Hypogeum at Hal Saflieni is a unique structure of planetary significance:

... it is the only megalithic monument which has been carved underground, and no parallels can be drawn with similar structures else where. It not merely testifies to the precocious civilization of the Neolithic Maltese, but is a surviving model of the several Maltese megalithic structures above ground. Unlike the open stone circles outside the Maltese islands, such as Stonehenge ... They are therefore rightly classed as the earliest temples on the planet.

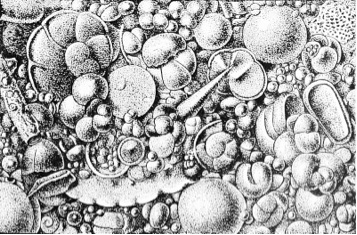

The authors bring forth the observations of T. Zammit that Hypogeum is in the district Tal-Gherien, translated as place of the caves. Close to the entrance of the Hypogeum are natural caves. The underground sanctuary is carved out of the soft calcified, fossilized seashells, part of the porous strata typical of the Mediterranean Basin's limestone that is eroded naturally by persistent water flow over time or yielding easily to the accelerated erosion of carving by human hands. Underneath the porous layer is impenetrable bedrock where drinking water accumulates at the levels averaging from 50 to 100 meters. This is where indomitable Olive trees of the Mediterranean find their nourishment. The access to living water is also an aspect of Hypogeum's Sanctuary function.

3. Globigerina, limestone composed of fossilized seashells

The Hypogeum is configured on three levels and organized as a system of inter-connected human made monumental tectonic spaces that are cave like. The space sequence proceeds from the most ancient and rudimentary upper level down into probably intentionally the womb-like main sanctuary below.

The Subterranean Sanctuary at Hal Saflieni paper cites an early twentieth century source commenting on the Maltase president: The discovery of the Hypogeum coincided with that of Knossos in Crete by Arthur Evans. The latter had subsequently extrapolated on his own discovery by identifying Crete as the cradle of civilization in Europe and the Mediterranean. But Knossos was a Bronze Age civilization, whilst that of Hal Saflieni was a Neolithic one (Mayr 1901,1908), and was therefore clearly an earlier civilization than Knossos.This is a tip of the iceberg surrounding multiple issues of the Hypogeum. If we stay with the observable phenomenon, the issues of spontaneous or planned narrative of the origins and assent of western civilization from Greek classical thought, art and architecture come up. Maltase megalithic temples and particularly Hypogeum disrupt this narrative of the cradle of civilization of Europe and the Mediterranean. Most temples in Malta face southeast to Africa. Some of the temples' layout (Ǧgantija on Gazo) or statuary reflect motifs of twins and twines present in African religions. Remarkable acoustic and tonal phenomenon link Hypogeum to painted caves and their resonances to what is today the south of France, Spain, Italy and Balkans. On another hand the sophistication and the instrument-like quality of Hypogeum have provoked some science fiction like hypotheses that burden the recognition of the Maltase achievement. As our paper is about the archaic sound making, we turn to the appreciation and reflection on Hypogeum's remarkable acoustic phenomenon.

The Oracle Chamber

T. Zammit identified the chamber adjacent to the main sanctuary as the Oracular room. In this space he has discovered a sophisticated stone apparatus that amplifies the voice:

A deep, low note uttered or hummed in or near the small cave, or the oval niche, resounds and vibrates in the chamber in a most remarkable manner, and the human voice is so much magnified as to become audible throughout the entire underground place."

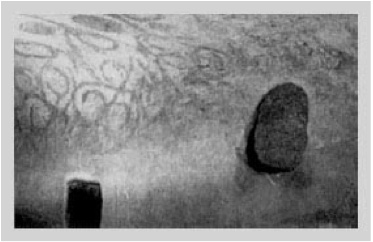

T. Zammit describes the Oracular room as having a "highly arched ceiling richly decorated with a red scroll interspersed with painted discs of different sizes." This pattern has a reason, as the decoration of ancient people was never arbitrary but always had context and reason.(Zammit 1925: 19).

The authors of The Subterranean Sanctuary at Hal Saflieni paper cite a number of researchers/commentators describing acoustic characteristics generated from the Oracle chamber, we shall summarize them here as a list:

- Two-feet wide hemispherical opening in the Oracle cave, at the height of a man's mouth, magnified sounds by about a hundredfold.

- Specially carved projection at the back of the cave near singing/speaking hole act as a sounding board designed with the profound knowledge of sound-wave movement and potential.

- Whole Sanctuary vibrates with the sounds of low tones while high-pitched notes stay in the Oracle chamber.

- Sound that vibrates throughout the Hypogeum "does not only energize the space but returns to energize, to regenerate, the maker of the sound"

This summary brings us back to the life work of Iégor Reznikoff, whom we cited earlier for having shown that in the majority of caves with intentional human inscriptions, the presence of wall paintings and drawings is highly correlated with the phenomenon of natural echo at that location in the cave, and especially so at particular resonant frequencies. Comparison of sound notifications on cave ceilings and walls studied by I. Reznikoff and very specific and particular inscription on the ceiling in the Oracle room and at other places in the Hypogeum, deserves a consideration. The Hypogeum markings are a similar motif of tight spirals and circles of different size. Like the cave inscriptions for resonant spaces, the symbols in the Hypogeum's Oracle chamber prompt us to pose an open question: Are they some form of notation for music memory, recognition and tradition keeping? The authors of The Subterranean Sanctuary at Hal Saflieni paper cite a fascinating observation:

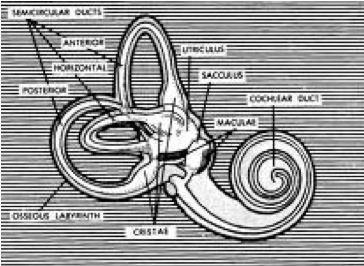

At this point an analogy requires to be made between the configurations of the human cochlea, the central organ of hearing, with the spirals which decorated the Hypogeum chambers so diffusely. This organ measures 5 mm, and is located in the petrous bone of the human skull. Its spiral shape which is repeated ad nauseam in bright red colors all over the Hypogeum interior cannot be considered as coincidental with the fact that acoustics played such a central role in the spatial system of the Hal Saflieni temple.

4. Cocholea of the human ear—Spiral on the right

5. Wall inscriptions above the main acoustic niche

The acoustic phenomenon generated from the Oracle chamber can be seen as an axis, an integrating force for the tectonic arrangement of the sanctuary. The sound was a central revelation for the variety of possible uses that could have happened there: ancient religious rites, initiation ceremonies, ritual magic, re-enactment of mythology, group or individual healing—medical practice, expressions of grief and gift for pilgrims.

Societal Sanctuary Function

R. R. Holloway in his paper, The Classical Mediterranean, its Prehistoric Past and the Formation of Europe [12] after setting the scene with a profound understanding of the social and political structure of the Mediterranean village asks a key question:

But we have not faced the question of what it was that permitted the citizen villages to unite in the face of great powers. The answer lies in the sanctuaries [our bold] of early Greece and Italy and the power of federation, temporary or permanent, that the federal associations based on them gave to their members.

R. R. Holloway's insights into the possible federation of small units through shared sanctuary could be a starting point in re-examining assumptions about ancient societies. A great number of cultural axioms in use today are based on the 19th century rise of national identities. Looking at the abundance of megalithic temples on the Maltese Archipelago may be one place to re-examine some assumptions about the ancient world, more as a point of discussion than a developed theory, and gives rise to a number of tentative hypotheses and open questions:

- Were the monumental temples on Malta the result of a number of regional coalitions across the Mediterranean involving people from neighboring, distant watersheds and islands?

- Were the celebrants coming to Malta from a greater geographical area than we have imagined so far?

- Was the Hypogeum the central, unifying temple, while others were built and maintained by different federations?

- Were the bones deposited there in the latter period carried from far away places as well?

- Is devotional, communal Polyphony a survivor of an archaic music carried home?

In closing this section of examining the ramifications of the example and the existence the Hypogeum at Hal Saflieni we reflect on some conceptual models that hinder understanding of ancient people and their expressions and achievement.

The first is the notion of primitiveness of ancient humans as backward or early, simple minded and even childish, doodling a few animals on the walls of cave in hope of catching them for dinner. This could be similar to some distant civilization seeing Christian representations of a lamb and dove as desired food items or animal worship.

The other hindrance is seeing some practical or ritual achievements of the ancients as being of alien and non-human origins, the issues surrounding achievements of the Great Pyramided for example.

Also presuming that, for example, the time old irrigation networks using gravity for a thousand years are primitive compared to modern electrically or gasoline operated pump.

The sometime simplistic views of matriarchal society as mere reversal of patriarchal attitudes where men are oppressed and without a voice and women rule with stone will. This perception is re-examined by the example of the womb-like space of Maltase Hypogeum that becomes vibrant and alive fully when it is activated by the deep man's voice.

Oral Tradition and Music

Examining multiple layers of the phenomenon of living culture often requires a team of researchers and experts to assemble the concrete facts and multiple sources yet this may still leave out the essence of the culture studied. For example although three Abrahamic Religions base their source and daily practice on revealed and written books but when they are integrated into communities they often merge or create connection through oral traditions, craft practices, unwritten mores, songs, dances and folktales.

The worldview in which oral tradition utilizes the capacity of the brain to keep large amounts of information through mnemonic ordering of meaning and facts, may have a completely different relationship to the externalization of information than does the following of a text.

A glimpse into this worldview where the dominant operational systems are preserved and communicated through the oral traditions may help reconstruct the intellectual achievements of ancient humans and help better understand the archeological and ethnographic remains of archaic cultures as different rather than primitive. Singing, clapping, drumming, moving and dancing may be an inseparable part of this mnemonic system.

To come close to this worldview, presided by the oral traditions, we shall look at transmission of remembered, sung and recited epic poems. In the seminal book on oral tradition and epic poetry by A. Lord, The Singers of Tales [13], there is a translation of a live interview with one of the last oral epic singing practitioners surviving among mountain regions of Bosnia, recorded in the 1930's by M. Parry:

When I was a shepherd boy, they used to come [the singers of tales] for an evening to my house, or sometimes we would go to someone else's for the evening, somewhere in the village. Then a singer would pick up the gusle, [bowed string instrument typical of the Balkans used specifically to accompany epic poetry] and I would listen to the song. The next day when I was with the flock, I would put the song together, word for word, without the gusle, but I would sing it from memory, word for word, just as the singer had sung it... Then I learned gradually to finger the instrument, and to fit the fingering to the words, and my fingers obeyed better and better... I didn't sing among the men until I had perfected the song, but only among the young fellows in my circle [druzina] not in front of my elders...

Now imagine any contemporary teenager first listening to an epic for several hours and then repeating it the next day from memory. By contrast, the non-literate shepherd boy was equipped with the necessary plasticity and capacity of brain independent from written record and entirely confident in the ability of comprehension, retention and reproduction through oral means alone. The recitations are approached from the general thematic over-sense to the particulars of the events in the story. The epic is held as a whole and as parts simultaneously, as a spatial and temporal continuum in the narrator's internal space. How many graduate students or doctorial candidates can do that with their thesis?

Music and festivals, celebrations and rituals

Herodotus—in his second book of nine part Histories [14] titled and dedicated to Euterpe, muse of music, sharing and well being, he writes about public festivals of Ancient Egypt. In this work Herodotus describes how The Egyptians hold their religious public assemblies often, "with the greatest zeal" and devotion. So the festival at the city of Bubastis for Pasht was not exception. Herodotus describes the festival:

They sail men and women together, and a great multitude of each sex in every boat; and some of the women have rattles and rattle with them, while some of the men play the flute during the whole time of the voyage, and the rest, both women and men, sing and clap their hands; and when as they sail they come opposite to any city on the way they bring the boat to land, and some of the women continue to do as I have said, others cry aloud and jeer at the women in that city, some dance, and some stand up and pull up their garments. This they do by every city along the riverbank; and when they come to Bubastis they hold festival celebrating great sacrifices, and more wine of grapes is consumed upon that festival than during the whole of the rest of the year. To this place (so say the natives) they come together year by year even to the number of seventy myriads of men and women, besides children.

This description points to a deeply established tradition of public festivals with definite music and choreographic elements as well display individual free expression of woman within the festival's framework.

Herodotus equates the Egyptian deity Pasht with Greek Artemis-the huntress but the Egyptian feline goddess also has some characteristics of Hecate-moon goddess. With the emblematic sun disc on her lioness /cat head she hunts by night. This fully empowered feminine goddess may point to the importance of some woman in the boat procession breaking away from singing, clapping and shaking rattles to instead cry aloud, jeer, dance, and pull up their garments. This division of roles between supportive music and rhythmic section as a container to a traditionally structured acting-out group, points to practices that bring trained and informed people to the Pasht festivals. Although they are not professional musician or dancers, everyone knows what to do just like people entering a Mosque or singing hymns in a Church. Not to over stretch the Herodotus example, it sets the tone for the paper's inquiry and opens questions about lost and found music traditions and oral transmissions in the cross currents of the Mediterranean and Black Sea's intangible heritage.

Egyptian Zar and Italian Tarantella

In looking for traces of discernable training and transmission of knowledge, we shall explore traditions and cultural phenomenon that happened in intimate and protected places often temporally adopted within a home or communal spaces. Beyond archeological fragments of dally life and survival, we focus on the activities, gatherings and festivals led and performed for and by women. Since these events were only carried out among the women, written documentary evidence is barely existent. What does exist are similar oral traditions to those even practiced today in some parts of North Africa, Eastern Mediterranean including Southern Italy and Asia Minor on the border of Iraq and Iran. There are two forms from this family of traditions that had more ethno-musicological and anthropological research than the others, they are the healing dances and music of Egyptian Zar and Southern Italian Tarantella.

S. D. Paich, the author of this paper, in his work Magna Graeca/Tarantella [15] wrote about possible relationships between the southern Italian dance Tarantella, particularly the Pizzica type, and the Dionysian festivals and Pan worship of Magna Graecia and parallel dance ceremonies in the Greater Mediterranean region. In that paper S.D. Paich quotes Antoine Furetière's description of Tarantella in Dictionnaire Universel of 1690:

Tarantula, small venomous insect or spider found in the Kingdom of Naples, whose sting makes men very drowsy, & often unconscious, & can also be fatal to them. The tarantula is so called after Taranto, a town in Apulia where they are to be found in great numbers. Many people believe that the tarantula's venom changes in quality from day to day, or from hour to hour, for it induces great diversity of passions in those who are stung: some sing, others laugh, others weep, others again cry out unceasingly; some sleep whilst others are unable to sleep; some vomit, or sweat, or tremble; others fall into continual terrors, or into frenzies, rages & furies. .... In some cases this illness can last for 40 or 50 years. It has been said since time immemorial that music can cure the tarantula's poison, since it awakens the spirits of the afflicted persons, which require agitation. [16]

Karol Harding in her article "The Zar Revisited" [17] wrote in 1996 for Crescent Moon magazine:

The Zar ritual is cathartic experience which functions for women in these cultures as effectively as does psychotherapy in western culture. It involves several aspects which all contribute to its success as therapy: The patient is the center of attention, and receives the help and concern of her friends and relatives. Her experience and feelings are recognized as valid. As Dance Therapist Claire Schmais explains, 'it is community based, followers and members are not sent away to be cured.... It creates sense of community while it heals, embracing the individual within a community.

Karol Harding's description of the Zar leader with her knowledge, harmonizing abilities, understanding of repression and means of relief, paints a picture of a highly trained experienced person leading deeply structured process:

Rituals are used to create the setting. They have specific players and roles: a leader, a drum corps, a 'patient' and participants. These rituals include an altar, the smell of incense, and costumes. Songs are chanted and drums play trance-like rhythms. The Zar provides a multi-sensory experience with sights, sounds and smells. The ritual sharing of food creates communion in all cultures and times. Thus, it is important to understand these rituals in the context of the total experience. [18]

These types of dance ceremonies for women were organized to facilitate, share, hold and express aguish, loss and maltreatment. For example at times of Crusades behind war lines widows, orphans and bereft future brides created a bonding experience. For thousands of years they taught each other rigorous techniques that found their way into pagan Greece, Byzantine Balkans, Catholic Southern Italy, Zoroastrian and Islamic Persia, Ottoman Anatolia, Islamic North Africa and Medieval Spain.

Ethnomusicologist Hassan Jouad, in his Les Aissawa de Fes—Trance Ritual describes the Aissawa Brotherhoods therapeutic trance dance:

...it should be pointed out that the practice of the ecstatic dance is not reserved for the sole followers of the [Aissawa] brotherhood. It is open to all, to anyone who suffers. Here, people with few resources, the elderly, the physically handicapped find, with the help of others, the occasion to be completely receptive towards themselves in all legitimacy. [19]

S.D. Paich in his paper Magna Graeca/Tarantella talks about an ad hoc or deeply established charitable institution that provides for the ceremony's expenses and of course for the ceremony's leader. This oblique, in some communities or clear-cut charity provides modes of living for the dedicated women who hold tradition and knowledge. This is an age-old practice, almost a common law institution, of a pastoral role for women. Sometimes unspoken vows of "poverty" and service are taken— as if to insure that the practices of music and dance ceremonies will be selfless and directed to the well being of the community and to the person who is in a process of healing. This was by no means a public office and it was not outwardly accepted in all the societies where it was practiced. Nevertheless, whether open, discrete or covert, it existed under all types of circumstances for thousands of years.

Part II

Plato, Pythagoras and Ancient Music

J. Godwin in his antoligy The Harmony of the Spheres, a Sourcebook of the Pythagorean Tradition in Music Writes:

Although Plato wrote his dialogue Timaeus some thirty years later than the Republic, the conversation it records is supposed to have taken place on the following day. The main speaker is Timaeus, a Pythagorean philosopher from Locri in southern Italy, and his subjects are the creation of the World-Soul, the structure of the elements, and the workings of the human body. This passage concerning the making of the World-Soul by the Demiurge, or creator god, has rightly been called „the most perplexing and difficult of the whole dialogue," for it is an inextricable blend of mathematics and music, astronomy and metaphysics. Even in Plato's own century it was a cause of dispute among his successors at the Athenian Academy.

Apeiron: A Journal for Ancient Philosophy and Science published J. B. Kennedy's article Plato's Forms, Pythagorean Mathematics, and Stichometry [21]. J. B. Kennedy is a science historian at The University of Manchester, Great Britain. He has worked on the long disputed secret messages hidden in Plato's writings. Using Stoichiometry ii that deals with an analysis of the variables in the elements in chemical reactions. Vastly expanded by computer algorithms, modern Stichometry has been developed to track, predict and analyze complex chemical reactions. Using Stichometry, J. B. Kennedy "reveals that Plato used a regular pattern of symbols, inherited from the ancient followers of Pythagoras, to give his books a musical structure". Here we quote J. B. Kennedy from the 2010 press release about the discovery sent by The University of Manchester:

A century earlier, Pythagoras had declared that the planets and stars made an inaudible music, a 'harmony of the spheres'. Plato imitated this hidden music in his books.In antiquity, many of his followers said the books contained hidden layers of meaning and secret codes, but this was rejected by modern scholars.

It is a long and exciting story, but basically I cracked the code. I have shown rigorously that the books do contain codes and symbols and that unraveling them reveals the hidden philosophy of Plato.

This is a true discovery, not simply reinterpretation.

This will transform the early history of Western thought, and especially the histories of ancient science, mathematics, music, and philosophy.

J. B. Kennedy continues:

However Plato did not design his secret patterns purely for pleasure—it was for his own safety. Plato's ideas were a dangerous threat to Greek religion. He said that mathematical laws and not the gods controlled the universe. Plato's own teacher had been executed for heresy. Secrecy was normal in ancient times, especially for esoteric and religious knowledge, but for Plato it was a matter of life and death. Encoding his ideas in secret patterns was the only way to be safe.

J. B. Kennedy concludes his article Plato's Forms, Pythagorean Mathematics, and Stichometry by stating:

Though the evidence reported here will need to be verified and debated, it does clarify, in a surprising way, Aristotle's once puzzling view that Plato was a Pythagorean.

Pythagoras is considered one of the fathers of western mathematics and music theory and a proto-scientist. As such his symbolic and metaphysical teachings were regarded as quaint like Plato's after him. Nineteenth century scholarship painted them as giants rising out of a ceremonially entangled and superstitious ancient world with clear thought and conciseness. In establishing the origins of western thought the overlooked and underplayed fact has been that Pythagoras, at roughly the age of twenty, went to the temple schools of Ancient Egypt and was trained there and in related or synergetic circles in Asia minor as well, before returning to Greek Territory at around the age of forty to teach a mixture of mathematics, music, astronomy and metaphysics.

Pythagoras

Pythagoras from Samos was born approximately in 586 BCE and died in 475. He was a son of an engraver of gems. Very little is known about his early years and his life in general.

Wim van den Dungen in his essay Hermes the Egyptian, dedicates a chapter titled The influence of Egyptian thought on

Thales, Anaximander & Pythagoras [22]. W. van den Dungen writes:" ''Anaximander and Thales were teachers, no "school" emerged after their death". In another place W. van den Dungen recounts:Iamblichus writes Pythagoras buried Thales and knew Anaximander before he stayed 22 years in Egypt and was initiated in the teachings of the priests of Thebes (plurality & unity of the Divine) and the doctrine of the resurrection of Osiris (the immortality of the soul).

We shall cluster some W. van den Dungen observations and extracts as they point to our interest in Egyptian roots of Pythagorean thinking:

[Pythogoras initiated a] "school" of thought, a teaching in which religion, mysticism, mathematics and philosophy were allowed to interpenetrate each other.[...] These speculative considerations took place "next to" physical inquiries into the nature of all possible beings. With his emphasis on numbers and the theology of arithmetic [...] he is credited with the theory of the functional significance of sacred numbers in the objective world and in music. [...] attributed to him [are], like the incommensurability of the side and diagonal of a square, and the Pythagorean theorem (well-known in Egypt and Mesopotamia),

Pythagoras was mentioned in Diogenius Laërtius' Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers containing biographies of the Greek philosophers written approximately in the first half of the third century AD. W. van den Dungen tells us that Diogenius Laërtius writes:

Pythagoras entered the Egyptian temples and learned the secrets of their gods. This is a remarkable testimony. The Egyptian gods were hidden from sight. Nobody, except Pharaoh and his appointed priests, could enter the "holy of holies" and face the deity. There was no communication between the deities and humans, for gods communicate only with gods.

The deeply researched observation and hard work of W. van den Dungen is honored here. His writing is in the realm of examining written records and understandably not relying on them, having a methodology for or maybe an interest in assessing oral traditions as possible source and parallel to the written word. It is burgeoning research, a collection of examples and overviews of which the work of W. van den Dungen is an example. W. van den Dungen writes:

In spite of these historical uncertainties, the contribution of Pythagorism to Western culture has been significant and therefore justifies the effort, however inadequate, to depict what its teachings may have been. [...] What could Pythagoras have learned from the priest of Memphis and Thebes?

Unity of the divine: the absolute is One and Millions, invisible by nature and manifest in nature's forms

Harmony of opposites: all fundamental oppositions are bridged by a harmonic "third" [Tetracord]

The sacrality of "10": Pharaoh, "son of Re", completes [a significant grouping of nine deities] the Ennead + 1 = "10"

Geometrical solutions to practical problems [related to, equated and generated from] the magic of symbols: sacred script and ritual speech [that] have powers beyond their physical form

Rule of silence: the Egyptian gods and their priests were out of sight and hidden-silence was gold

C. M. Woodhouse in his book on the renowned fourteenth century Byzantine teacher of Platonism Georgius Gemistus Pletho, who inspired Cosimo Medici to open Platonic Academy in Florence that went underground for almost a thousand years, writes about the philosophy omissions that were left out from his excerpts and summaries:

In the higher studies, especially philosophy, he preferred oral teaching. He [Gemistus Pletho] liked to emphasize that Plato and the Pythagoreans distrusted the written word as the means of communicating their most important ideas. [23]

Even contemporary music training through master classes acknowledges the difference between what is written and what is experienced then remembered and integrated through the body.

L. Crickmore the musicologist of the ancient civilizations in his essay Egyptian Fractions And The Ancient Science Of Harmonics [24] writes:

There is a img-fluiding body of evidence to support the hypothesis that in ancient times there existed throughout the Near East a common mathematical approach to the definition of musical pitch in terms of ratios of pipe or string-length. This tradition became known by the time of Plato as the science of harmonics. [...] It seems reasonable therefore to assume that the science of harmonics would then have been accommodated to the various regional systems of arithmetic in use: sexagesimal in Mesopotamia; Pythagorean in Greece and in Egypt by means of Egyptian fractions.

A number of authors including L. Crickmore and J. Godvin see the concept of 'Music of the Spheres' as an expression of the ancient preoccupation and study of the origins and life cycles of the universe as part of their cosmological interpretation and models. Music, harmonic ratios and resonances play a big part in the Pythagorean—Platonic cosmological paradigms. Seven notes of the Heptachordal scale reflect the varying speeds of revolutions of the seven known planets of the ancient world. Archaic harmonic system unites the two basic Tetrachords by establish the upper tone of one as the lower tone of the other into a Heptachord. L. Crickmore articulates beautifully the emergence of octave 'Later, the fixed stars were accorded a note of their own, and the music of the spheres was considered to be an octave species or mode'. Attributed to Pythagoras in the western tradition, is the revising the Planetary Heptacord into an Octochord. L. Crickmore writes:

It will be noticed that unity (sometimes called the Monad by the ancients) is the fulcrum of this structure [Pythagorean music system], as it was of all ancient mathematics. In modern times, the fulcrum of our arithmetic is zero, which was unknown [not used] as a number to the ancients.

In thinking and comparing Zero with Monad, the difference between the two is that zero is helpful in additive calculation and thinking, it is a devise, while Monad is indivisible and requires respect and discretion. Continuity and consistency of intangible harmonics of inter-planetary and galactic space is demonstrated seamlessly and empirically by logical, proportional divisions of vibrating string and recognized in the range of audible sound for the human ear. Doubling the string lowers the tone while shortening heightens the pitch. L. Crickmore points out "the ancient Greek double -octave system, known as the Greater Perfect System, later evolved".

Empirical demonstration of implied harmony of the world in ancient music and practical use of Egyptian Fractions are related phenomenon. While zero offers expedient numerical movement in both directions of plus or minus, Egyptian Fractions lead tangibly smaller and smaller parts to monad as a unifying presence. This in terms of music and sound evolves in to higher and higher pitch and in post Pythagorean Greek music and subsequently western music's higher tones are considered more spiritual. This may be the defining difference with archaic music and singing that through deep sounds that reverberate through the entire body and engage molecules and cells of living organisms as celebration of monadic harmonies. The higher the note the less of the body is involved but only the head and then only the top of the scull. While in archaic singing, caves or temples are the primary instruments of ritual resonance and the music was associated with the memory and connection to the experience in those places.

The archaic music is in a similar relationship to written notation as the orally transmitted myth and stories are to written records. This is the difference and complimentary contribution between musicological research of L. Crickmore and I. Reznicoff. One looks at surviving documentary evidence about the ancient science of harmonics among the glyphs and inscriptions of numeral, words and diagrams, while the other reads the cave itself and the pictorial and other non—verbal markings found there.

D. R. Fideler in his introduction to K. S. Guthrie, The Pythagorean Sourcebook and Library [25] writes:

[...] Knowledge itself is the third, harmonic element which conjoins the two poles of subject and object. Knowledge then is unifying, much like the harmonic ratios of the musical scale [...]. Moreover, as we shall see, to the Pythagoreans the knowledge of divine harmony can be either abstract of experiential, or, indeed, both.

D. R. Fideler develops observations on Pythagoren notion of 'undeniable influence of numbers' on human psychological inner moods and comprehension 'through the medium of music, depending as it does on numerical proportion'. D. R. Fideler gives examples of different ratios of notes and music proportions that can express happy, light emotions or like the minor third evokes longing and meanigful sadness. As we mentioned earlier, when presenting the research of I. Reznicoff, that he noticed the archaic singers' awareness of the tonal ranges and the effect of sound on the human body and state of mind. D. R. Fideler continues:

The fact that Number can influence a person's emotional state is indeed mysterious and points toward a dimension of qualitative Number which trandscends the merely quantitative. Related to the question of music and harmony is the principle of resonance: two strings, tuned to the same fequency, will „i vibrate if only one is plucked, the unplucked string resonating in sympathy with the first. This, of course, is accomplished through the medium of the vibrating air, but the principle underlying the phenomenon is one of harmonic attunement.

D. R. Fideler points out that Pythagoras and the Pyhatoreans (and we add Plato and Neo-Platonist) represent human psychology as an imploded reflection of totality, a microcosm. D. R. Fideler discusses the Pythagorian notion of the human soul as a harmonizing factor in unifying all the elements of an embodied human being. This elusive, sapient unifier is particulary attuned to the ratios of musical proportion as a form of resonance in the audible and inaudible worlds. D. R. Fideler wrote:

Moreover, by experientially investigating and employing the principles of harmony in the external world, one comes to understand and activate those same principles within. This idea in fact underlies the Pythagorean approach to mathematical study. The Pythagoreans divided the study of Number into four branches which may be analyzed in the following fashion:

- Arithmetic = Number in itself.

- Geometry = Number in space.

- Music and Harmonics = Number in time.

- Astronomy = Number in space and time.

D. R. Fideler points out that Plato, continued the Pythagorean focus on numbers, their relatshonships and resonances and expresed it as an educational curriculum set out in the Republic, the work we disscased before where the hidden music harmonic score is embedded. For Plato, D. R. Fideler quotes: ''geometry is the knowledge of the eternally existent.''

Three Folksongs

In the world of audible sounds seemingly simple folk songs that could be easily sung or recognized by most people, play a significant role in community identity and a means for coming together. Contemporary electronic commerce exploits this organic need for identifiable, composed sound. Commercial popular music and traditional folk songs emerge from unpredictable or hidden roots often not even clear to their makers. In collecting, researching and studying the origins and existence of popular and folk songs, the performer's interpretation and the circumstances of the first hearing play a significant starting point. The critical writing on structure and societal intention of the songs and to approach a description of a possible meaning and context, often the only available resources are non-verbal elements, music elements, hearsay, contemporary circumstances of the song and naturally the performer's disposition and gifts. The examples of the following three folksongs point to the intricacies and riches of cultural contexts surrounding landmark songs.

First Song-Pastoral Tradition

A piece that retains some connection to the archaeic singing style of call and answer is the Romanian tone poem Cand ciobanul si-a pierdut oile [26] -When the Shepherd Lost His Sheep. The example was collected and recorded by Constantin Prichici in 1956. It was performed on a caval by Neculai Tafta, a country priest from the village of Negriliesti, Vrancea in southern Moldavia. Compact Disc notes for the song read: One impressive item in the Romanian pastoral repertory is the well-known musical legend of the shepherd who has lost his sheep—a kind of folk instrumental tone poem that shepherds would perform on any of the instruments connected with pastoral life, such as the bagpipe, the six-holed fluier, or as here, on the caval—a long, five-holed rim-blown straight flute.

The original versions are a combination of spoken narative and music. Since the story is so familiar to everyone, is often left out, which creates a rich internal imaginal field. The audience guessing the fable's scenarios amid episodes is facillitated by performers enacting emotionally the story with the melody:

The sheperd thinks he sees his sheep and runs toward them only to find some white stones in a meadow; he comes upon a dead lamb savaged by wolves; he sits by a stream and is consoled by the water and wind, and so on. Around this simple program the musician improvises his melodies, [...] alternated with dance tunes, introducing musical episodes as they occur to him. The piece always ends with a dance of joy.

The two and a half minutes extracted from an eighteen minute piece is music describing the shepherd's grief and the moment when he runs toward the white stones mistaking them for missing sheep.The familiarity with the story offers deeper exchanges where imagination and music unite the listeners and the performer.This interplay of inner and outer, stated and imagined as a individual and community experience is one of the primary reason and function of folk songs since archaic times. S. D. Paich, the author of this paper in the conclusion for River of Images-Interplay of External and Internal Image Making [27] writes:

We started with the notion by Aristotle, that there is not a thought without imagination. Then the premise that the physical body continuously works to keep its equilibrium and adjusts processes for the physical survival. We cited and established examples of imagination almost as if a physiological organ. We observed the fact that the internal self produces images and nonverbal scenarios to help us deal with life's complexities. An example of this is the involuntary image making process that happens nightly in dreams. The relationship of memory and imagination as well as cultivated imagination vis-Ã -vis oral traditions, was touched upon. Finally, we analyzed and contextualized a number of phantasmagorical examples from the history of culture and reflected on skills needed to make externalization of the imagined possible.

The song Cand ciobanul si-a pierdut oile is an example and carries the issues quoted above with imagined and executed parts and the societal bond it creates, but above all and beyond any theory it is one of world beautiful and expresive songs.

Second Song-Migrations of a Single Song-Wa Habibi (My Beloved) sung by Lamia Bedioui

The Provencal Carnival song Adieu Pauvre Carnaval reappears as a Maronite Easter hymn in Lebanon known as Wa Habibi that may have roots in medieval Mozarabic Creed of Arab speaking Christians in Spain. One of the most moving recordings of Wa Habibi is by a Tunisian singer, Lamia Bedioui [28]. This haunting melody appears also in Le Fougere by the Neapolitan composer Giovanni Pergolesi (1710-1736). The first work to establish Pergolesi's reputation was his sacred drama, La Conservatione di San Guglieme d'Aquitania (1731), 'given its first performance by his fellow students at a Naples monastery' [29]. Guglieme d'Aquitania, or Guillaume IX of Aquitaine (1086-1126), is recognized as the first Troubadour of Provance. Guillaume as Troubadour used the Romance vernacular Occitan or Provencal for his poems. His titles, which point to a definite geography and place, are inseparable from Troubadour territory.

Fin d'amour, courtly love as a cultural phenomenon, brought fresh elements into the social sensibilities of the feudal Christian world of medieval Western Europe. It provided the ecclesiastically dominated culture of Europe with a poetic language for the experiences of love, both secular and sacred.

It is more and more recognized that Troubadours and Guillaume IX's inspiration came from Arab and Persian poetry and music and a century earlier writing like the Andalusian proto-Troubadour, Ibn Hazm (994-1064) exemplified by his manual of love titled The Ring of the Dove.

One of the most comprehensive manuscripts on medieval music, The Cantigas de Santa Maria, was commissioned, and possibly partly composed by, Alfonso X (1221-1284). The codex's illustrations show Arab, African, Jewish, and European musicians performing together on a remarkable variety of instruments. It is a celebration of diversity, vitality, and mastery of professional—and probably itinerant—musicians. Julian Ribera in his book Music in Ancient Arabia and Spain [30] points out that the inexplicable structure of the cantigas to the ears of ecclesiastic and western music historians lies simply in the fact that the compositions follow Arab music form and inflection.

After being suppressed and silenced following the Reconquista movement inspired by the Catholic Church in Spain, little is known about the Mozarabic chant. The surviving music is written in pre five line notation system and is known as neumes, middle English from classical Greek word for breathing pneuma. These neumes, imaged below show the contour of the chant, but with no pitches or intervals, these were left to the musicians to decide based on transmitted tradition and according to their vocal range and devotional interpretation.

Wa Habibi musically carries so many characteristics of Arab medieval Spain's devotional singing, resembling Muezzin's call to prayer and its lyrics that echo literature of Sufi and other Muslim devotion brotherhoods. Lamia Bedioui in the 2001 live recording, preserved on the Terra Nostra compact disk, brings the spirit of the song to the listener and inadvertently all the cultural and emotional references come to life. The lyrics open with evocation familiar in classical Persian poetry but uncharacteristic for a church hymn:

My beloved, my beloved

What state are you in?

He who sees you, for you would cry

You are the one and only sacrifice

The life of this song defies the history, oppression, appropriation and historic or musicological analysis. It is a testament of the ability of the refined organization of sound to move human emotions and create connection.

Third-Everyone's song : Uskudara gideriken aldida bir yagmur

Traveling on a steam train in the fifties from Belgrade to the Dalmatian coast, that took an entire day and night, part of the route was on a train that carried families and people from Turkey, Greece and Bulgaria to Western Europe. Lots of food was exchanged even if people did not speak common language. As we were children from the Radio Belgrade children's chorus going to the seaside annual holiday which was our pay for the hard work, we loved the songs and they were easy to sing. In middle of a medley of many songs suddenly as we began to sing one folksong in our language, we were joined by a Turkish family singing it in Turkish and after a while the reserved, quiet Greek engender in the corner, joined by singing it in Greek. After lots of gesturing and linguistic experiments to explain the meaning in several languages, it was clear that each group thought it was originally their song that influenced the others. From the point of view of the song each group was right. The passionate multi-ownership of this song is the significant example of how meaningful music is closely and almost inextricably woven into society and peoples' lives.

When it comes down to music and sound performance, life's incidents, like the one we included above shed light on the communal and individual need for poetically ordered soundscape that resonates in human biology, psychology and the social environment.

The history of this song can only be very partially traced through the vast territory of Mediterranean and Black Sea watersheds. It may be the cause of one melody that has traveled from the Caucasus, Persia to the Asia Minor, Levant, over North Africa and then to Spain. After the expulsion of Arabs, Jews and Arab speaking Christians from Spain, the song migrated to Ottoman Turkey via land and sea. The song is known in Turkey today as Uskudara gideriken aldida bir yagmur. In Greece it is known as Apo Xeno Meros, in Serbia, Bosnia and Macedonia the song is mostly sung as Ruse kose curo imas, with rich variety of other versions in Bosnia. Albania and Bulgaria have they own version. In the Arab speaking Middle East it is known as O, beloved, beloved, in Palestine as O Prophet of God, the Hebrew version is I shall sing a song.... The medieval Spanish version in the Ladino dialect is Siente Hermosa or Durme, Hermoza Donzella and is very similar to a Moroccan version.