Giving Birth to a Performance

Some thoughts on dynamics of creating a theater piece

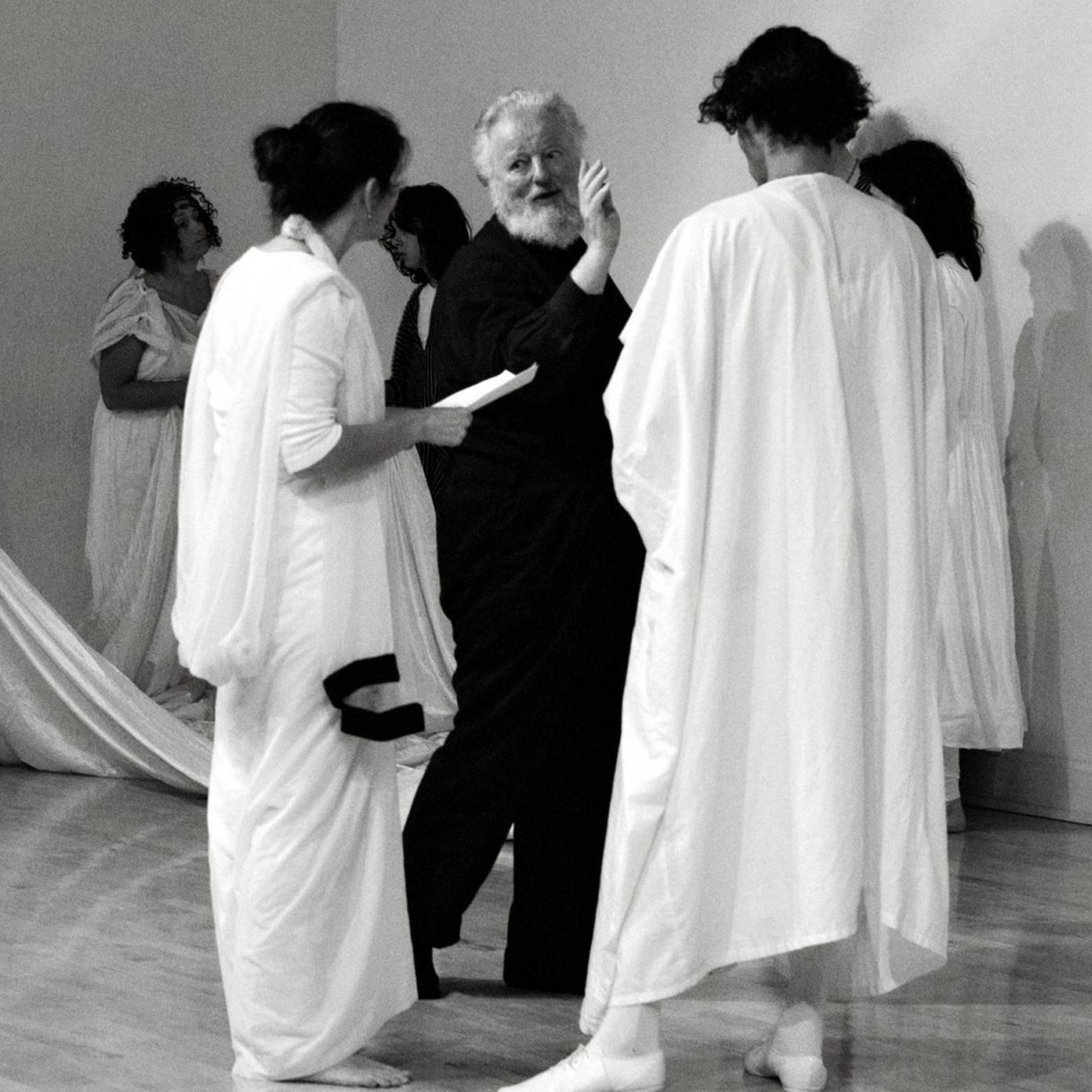

Slobodan Dan Paich

Director and Dance Maker

Artship Ensemble, San Francisco, USA

Page No. 1

Abstract

The paper is based on examples from a number of performance and training programs carried by Artship in the last twenty years. For the sake of communication and discussion, the examples and reflections follow the ensemble's ongoing weekly process of rehearsals, skills-building, inspirational improvisations and co-creation of the matrix for the emerging performance. At Artship the new project goes through a number of interrelated but distinct phases. Because the ensemble dos not start with a text or score, we use the term matrix for all the repeatable elements of a live performance. This matrix is born through improvising, incubating, remembering, cherishing and sharing. For Artship Ensemble, a theater matrix is unified field, a holder of all the written and orally transmitted and remembered elements of the expressions. This paper is not an attempt to idealize a practice or come with any universal answers. It is intended as a sharing of the successes and straggles of number of project tackling emerging paradigms of working together, celebrating doing and making intelligence and looking for a deeper sources of freedom of expression. The paper originally intended for the Ensemble members is sharable with people interested in this type of work.

Introduction

Context, Issues, Questions

Just as quantum physicists are discovering some of the same physical similarities between subatomic structures and astronomical phenomenon, genetic engineers are discovering an inner matrix of cells and chromosomes possibly resembling the same characteristics of larger organisms, societal patterns, and cultural structures.

Page No. 2

The more general questions here are:

- Are there ways of knowing and weaving human myths, stories, rituals, and performances that echo the hidden depths of the molecular and cellular dynamics of each human being?

- What is the function of imagination in neurological and societal phenomena? Specific Practice

This paper examines Artship's idiosyncratic process and—for the sake of communication, discussion, and sharing—articulates five distinct and interconnected phases of the process:

- Improvisation

- Incubation

- Emergence of the Matrix

- Cherishing the Matrix (rehearsals)

- Sharing the Matrix (performances)

This paper is based on notes from the Artship Ensemble's current practice,1988-2009, and Slobodan Dan Paich's theater initiatives since 1962. These notes were originally intended for the Ensemble members and practitioners interested in this type of work. The reason for these notes was to address and articulate issues of the complexity and subtlety of creating—and continuously recreating—a theater piece, addressing the intangible fact that there is always more to a score, text, or any notation for a performance. At Artship, instead of using the terms text or score, the term and concept of matrix is used for all the repeatable elements of a live performance. A definition of matrix may be: A generative relationship or living blueprint, so unified that, as a whole, it transcends all its individual elements; it is greater, and more alive, than any description or index of its parts. For Artship Ensemble, a theater matrix is a unified field that holds all of the elements of expression engaged in the performance: image sequences, choreography, stage action, music improvised and scored, the text's narratives and dialogues, and all the written and orally transmitted and remembered elements.

Improvisation

Louis Pasteur (1822-1895), the father of contemporary microbiology who invented and discovered causes of many diseases, is believed to have said, “Chance favors the prepared.” In his earlier paper, Art/Science: A Problem-Solving Model as a Unifying Principle of Creativity in Art and Science, the author discuses the relationship of preparation to discovery in a section titled Preparing the field and gathering elements for research. As an opening to the full discussion of the Artship experience of theater improvising, we shall reproduce it here with minor notes relating to the general narrative of this paper:

Page No. 3

As we follow some of the aspects of problem-solving as triggers of creativity, naturally, the significant part of the process is preparing the field and gathering elements for research. In 2 this seemingly obvious accumulating data phase, laden with facts and findings, exists the paradox of an inadvertent creation of an empty space—a field for significant connections to happen. Calling it an empty space may not be accurate, as it is an internal activity of the brain. Perhaps it is only momentarily empty. Maybe it is more a phenomenon of subjective timing than of an introspective space. Researchers have found that when people are losing memory, such as in cases of Alzheimer's, imagination comes in and the blanks are filled. This of course is devastating to the friends and family, as some unexpected and seemingly irrational connections are made. Every night, dreams offer these unexpected experiences to everyone. The moment we relax our rational guard or thinking habits, a compensatory flood of involuntary imagining comes in and fills our internal space. A natural process of all living beings, the imagination offers an experiential field with an infinite number of connections. In the case of problem solvers, this natural process is very helpful. The German chemist, Kekulé, wrote about his discovery of the idea of the benzene ring: But it did not go well [the writing of his chemical text-book]; my spirit was occupied with other things. I turned the chair to the fireplace and sank into half-sleep. The atoms flitted before my eyes. Long rows variously, closely unite; all in movement; wriggling and turning like snakes. And see, what was that? One of the snakes seized its own tail and the image whirled scornfully before my eyes. As though from a flash of lightning I awoke. I occupied the rest of the night in working out the consequences of the hypothesis…Let us learn to dream, gentlemen. (Beveridge, 1950)

It seems also that in the processes of art creation and art improvisation, this relationship of chance and preparation is critical. Because of that, improvisation plays a very important part in Artship's incubating and ongoing process. In that process, at the regular rehearsal, improvisation evolves after limbering warm-ups and skill-building. The atmosphere is tuned and prepared by specific musical modalities within a chosen perimeter, but also elements of silence and inwardness. Before the improvisation, the work of the company class takes place discreetly within parallel warm-ups, and both are done without verbal prompting. Within the container of the company values and mood, the stage is set for improvisation.

Accepting the limitations of participants' cultural affinities, body types, ages, and levels of mastery, the process unfolds. Rather than looking for extraordinary, unusual, large-gesture elements, we start with an attempt to find a unity-in-diversity of all the people on the floor. They are not necessarily doing the same thing, as in a gymnastic routine, but rather participating in an intangible unity and creating a commons of practitioners.

In the Artship process, the theater director is more of an eyewitness, an observer and holder of the space. The subtle relationship between the ensemble—the doers—and the director—the witness—is the container for all of the ensemble's potential. The director's role implies patient, careful watching. Through this witnessing, potential breakthroughs and further ideas for the performance are revealed and shared. Also, through witnessing, the personal development of ensemble members and the collective qualities of the ensemble are revealed. Here, a people-specific work begins to emerge.

Page No. 4

This aspect of watching and witnessing by the director is not unique to the Artship process; all directors or choreographers do that to an extent. However, in the Artship process, during the initial stages of giving birth to a performance, holding and witnessing are the predominant modes of direction. These modes give room for the collective wisdom of the ensemble to respond to the thematic kernel. Another aspect of Artship's work is a continuous research into archaic and traditional cultural practices as a means for enriching and informing our contemporary art practice. The ensemble then integrates these traditions to enhance performance mastery and communication. Some of the research findings directly or indirectly influence our improvisations. In the process of improvisation, moments sometimes arise that resemble the concentrated energy of conception. These conception moments often appear miraculous, and are the result of the subtle and complex coming together. There are schools of thought that give president to improvisation over all other aspects of performance creation. On the other hand, there are also schools of theater production— often based on a text—that see improvisation as minor tool. The Artship Ensemble sees improvisation as first phase in collectively giving birth to a future performance. It may be of interest to reflect for the moment on modalities of improvisation and its stated, or implied, cultural and artistic perimeters. For example, in theater workshops based on early twentieth century experiments, participants express creatively in that particular modality. We have never heard anybody in a Jazz improvisation suddenly sounding like Gregorian chant or an Armenian lament. It also may be of interest to reflect on certain limits of the improvisation process. If the improvisation becomes an end in itself, it can develop into a habit or regressive practice, which produces similar content (which in itself could be liberating). The Artship process acknowledges the framework of improvisation within the broad thematic mood of the future performance. We do not mind idiosyncratic repetition when it is for the emergence of a player's expressive range. In other words, we are not always insisting on breakthroughs and never-seen-before expressions, but values the simplicity of being an ensemble, being together as we were the week before. In the continuum from improvisations to performance, conception moments emerge. When that happens, the improvisers do not feel any different from any other moment in the improvisation process. These moments became significant—charged—only when shared and acknowledged by the doers and the witnessing director. The moment is captured, remembered, and held as a living seed. The moment when a player spontaneously acts out a poetic expression significant to the future performance is ephemeral and passing. In this remembering, the role of both the director and the ensemble as the keepers of the emerging matrix begins. The delicate interplay of holding, doing, and thematic defining within the company mood becomes a lunching pad into the unknown.

Page No. 5

Incubation

In this tender phase, the embryonic elements of the future production are held. When the warm-up or the parallel, discrete company-class is completed, a few rudimentary scenes of the envisioned production are acted out. The scenes are approached in an open-ended manner. Music plays an important part in this as it both holds the elusive mood of the semi-articulated intentions and gives an emotional underpinning. This phase is, in a way, the womb of the production. The scenes are the formative matrix-cells of the production.

A description of amniotic fluid can give us a starting point for thinking about the growth of an Artship performance matrix:

Amniotic fluid, or liquor amnii, is the nourishing and protecting liquid contained by the amnion of a pregnant woman. Amnion grows and begins to fill, mainly with water, around two weeks after fertilization. After a further ten weeks, the liquid contains proteins, carbohydrates, lipids and phospholipids, urea and electrolytes, all which aid in the growth of the fetus. In the late stages of gestation much of the amniotic fluid consists of fetal urine.i

This description so beautifully expresses the transforming quality of natural processes. What is interesting is the transformation of the fluid from water with elements aiding the growth to liquid saturated with post digestion fluids that are potently toxic. This changed characteristic of the surrounding fluid is one element signaling the change from fetus to newborn. The gestation period, natural timing, and the change of molecular “atmosphere” contributes to the irresistible push of all concerned to give life, to externalize a new entity. In a similar way, the sweetness of improvising and incubating are the means both of nurturing and of propelling an emerging performance. In Artship's process, the moment comes when improvising gives a way to consolidating and implementing or developing a particular mastery needed to carry a performance through. If either improvisation or incubation become ends in themselves, soon the vitality and desire to push gets smothered, and regressive content emerges. Such content, from a therapeutic point of view, may be an excellent container for self reflection—but in the process of creating a sharable, repeatable matrix for a performance, it may be detrimental if it is valued above all other processes. In the Artship's performance development, a certain amount of improvising and incubating is welcomed, necessary, and inspiring. Each re-convening facilitates a little bit of self-knowledge, the artistry of performing, a connection to others, and the recognition of one's place in the ensemble process. This re-creates the atmospheric incubating conditions each time. The incubation process is very close to improvisation, but the incubation process has thematic, visual, or sound elements somewhat more specific, repeatable, and potentially (or actually) related to the future performance. The matrix is not yet totally fixed.

Page No. 6

Emergence of the Matrix

In exploring the articulations of containers for the creation of theater performances, every type of rehearsal process and every type of space—to prepare, rehearse, gather, or perform—is valid. What we are saying is not dramatically new or never experienced before. The centuries-old art of theater and its associated crafts was developed for efficiency and assembled with as many pre-made and pre-trained elements as possible. In traditional theater, the experimentation or acquisition of new skills is kept to a minimum, or is done in a pre-production phase; it is not a part of the process. In Artship's process we give room and encourage the crossing of disciplines and building of new skills. We also bring in some key nonverbal elements that will give birth to the future look, feel, and general aesthetic of the piece, elements of the costumes, scenery, props and music. The place is tuned with the inspirational explorations towards the upcoming performance. 5 The most crucial part of the container are, of course, the players. Their ability to leave some of their daily burdens—as well as technical prejudices of their craft—at the door, is a bonus, but not required. The condition of regular rehearsals, held at a predictable time and place, is also a strong element of building the matrix. Some stability has to be there. So what is this matrix? And why do we think that its creation is different from mainstream theater practice? Although we have already thought about a possible definition for the term matrix, consulting several dictionaries and thesauruses, further commentary may give more understanding of our use of the term: Matrix as a womb: the living container for both the emergence, and the nightly reconstruction, of a performance. The term matrix has also been used generally to mean the principal metal in an alloy, as the iron in steel; a binding substance as cement in concrete; a mold or die; a blueprint; the formative cells or tissue of a fingernail, toenail, or tooth. In our case, the emerging matrix is the principal and binding substance for the repeatable elements of an Artship performance. Although some part of this matrix may be as static as a sculptor's mold or a machinist's die, a closer conceptual model—and the aspiration of Artship's process—is the concept of a living blueprint, like a genetic code. Just as genetic code is a set of traits—intentions deeply embedded throughout an organism—the aspiration of Artship's process is that its performance matrix is a living inspirational set of directions for creating and operating a living mythos, a story. Just as a natural form of memory is imbedded inside the cells that are at the roots of nails, teeth, or hair, the Artship ensemble begins to generate a performance with a number of more or less nonverbal elements, out of which the performance grows. Three examples The following three examples will show the elements intended to both help the emergence of the matrix and later be its stylistic holders.

Page No. 7

• Tarantella, Tarantula 2006 Home Season & World Premiere, ODC Theater, San Francisco

The Tarantella, Tarantula production began with three notions: how to give shape to a new performance, present the phenomenon of tarantism to modern audiences, and open the ensemble to a new thematic atmosphere. Initially, no script was used. Instead, the ensemble reconstructed Tarantella dances and learned to play traditional Tarantella music, including the use of Tarantella tambourines. To address, express, and explore the involuntary movements and spasms of a person in a Tarantella trance, we fabricated a special sheet with which to toss a nearly anatomically correct life-size cloth mannequin, which was also created by the ensemble.

Burning of the Ancient Library of Alexandria 2009 Home Season & World Premiere, Counterpulse, San Francisco

For the emergence of this performance, the ensemble experimented and played with a closed loop of string with a twelve-foot (four meter) diameter. Ultimately, this evolved into the opening scene. For a long period, the string was the ensemble's main incubating element. This string was based on records of the ancient Egyptian practice, the stretching of the cord, a preparation that established the ground plan of a building's foundations. Subject to immense ritual, this preparation set a building's four corners, oriented them to the cardinal directions, and brought the building into a vital relationship to the constellations.

Page No. 8

Page No. 9

The other major incubating element used by the ensemble was a set of thin cane sticks. The participants (ensemble members, guests, and auditioning artists) each held two sticks. They assembled, sometimes standing in a circle, and each one in turn led a short sequence of stick movements while the others carefully echoed the combinations. This exercise contributed greatly to ensemble-building and created a visual language for the piece. A third incubating element was a large silk sheet 24 x 26 feet (7.5 x 8 meters). In the hands of the participants, it went through many scenarios and relational combinations. Ultimately, it became the main image for the final scene.

Page No. 10

The ensemble initially experimented by singing with a number of sound producing objects, but in the end we settled for a metal wreath that sounded similar to an African thumb piano when plucked.

Page No. 11

The ensemble enriched this plucking and singing with explorations of prehistoric traces of ancient music as well as Mediterranean folkloric music and dance. Much of the music selected used extended note duration, simple harmonics, and drones. Burning of the Ancient Library of Alexandria concludes as the character Phoebe, a student of the main character, Hypatia, emerges from the large, white silk sheet, and delivers the final lines of the play while putting on a big black cloak. To make this moment credible, we began to choreograph a short piece so that the performer could understand the physicality of the cloak: to feel it, be one with it. This choreography was not seen in the performance. It was implied by the way the performer handled her costume. Although the ensemble had no idea what our next performance would be, while working on this parallel choreography, we realized that here was the seed—the concentrated essence—of what we hoped would emerge as an evening-length performance for the next year's home season. That seed is now already in its early incubating phase with the title Tender Stone.

Tender Stone 2010 Home Season & World Premiere, May 6 to May 16, 2010 CounterPULSE Theater - San Francisco

Page No. 12

Based on the nurturing wisdom of women storytellers of the Persian and Mogul empires, this Artship Ensemble performance intends to tell a poetic story of passion, love, betrayal, and constancy in the turmoil of the politics of the day. Tender Stone attempts to call up a collective memory, evoking an ancient wisdom and bringing it into our contemporary world. The current interest of the company is to look into and express the dramatic potential of the hidden depths of the molecular, cellular, and imaginative self of each one of us as echoes of primordial myths and ways of knowing. Parallel to the large black cloak, the non-verbal elements used for incubation include a set of ropes tied in conic forms inspired by the molecular structures and strands of DNA. These rope-clusters, made of units fifteen feet tall and four feet across at the base, will be constructed over time by the ensemble to hang from above and define the space. Another incubation element used to create the matrix for this play is a set of stage plants that are attached to the performers' arms. The ensemble is also experimenting with humming a cappella, based on modalities of Persian, Armenian, Kurdish, and north Indian music. All of these elements are intended to help the emergence of the matrix and will later become its stylistic holders.

Page No. 13

Cherishing the Matrix (Rehearsals)

In this stage, the work resembles any other production, with the director more in the forefront, crafting the implied psychology, the style, and the aesthetic of the performance. The fact that the generative costumes, props, and some set elements have been there from the beginning of the process, and are not a surprise, contributes significantly to the players' ability to hold the totality of the imminent performance. In every type of rehearsal process, time is compacted—almost imploded—to get things done and to master all of the elements of a performance. It is presumed that the players have an attitude professional enough to carry the performance through regardless of what they think about it. In Artship's practice of using repeatable elements for a performance, an attitude of care—and an attention to the living pattern of the performance matrix as a whole—is cultivated. So the matrix is cared for as an offspring, the result of the ensemble's process. If and when that happens, a very fine and special atmosphere for the play is created, which can potentially have an effect on the company and an audience.

This cherishing of the matrix helps also in the process of adapting and re-conditioning the play into new situations or different performance venues. It is as if an heirloom, a special family carpet, is unfolded, fitted, and adapted to fit a new place.

Page No. 14

With this stage, the performance is comparable to any other production and follows the universality of theater performance communication that hopes to reach an audience. The subtle conceptual difference in the Artship process is in the cultivation of a sense of sharing the matrix at hand. It is not something only to present, display, and exhibit—but also to share. Great performances and performers do that almost as a conscious—or at least deeply sensed—trade secret. In the Artship process, this sense of sharing the poetic worth of the play—its delicate treasures—is cultivated openly with all involved. It is always an experiment: a probability, not a requirement. When it happens, we are lucky. In other words, the hope is for the magic of the performance to come to life in the imagination and the inner world of the audience, where score, text, plot, and the sequence of steps all come to life not only through the matrix—but are experienced inwardly as a matrix.

Page No. 15

Final Words

In an earlier paper written in 2007, Scenography and Genius Loci, the author concludes with a section on inner imaging and personifying functions in a section entitled, “Genius Loci and the Need for Stories.” The paper posits an hypothesis that in the archaic recesses of our being we ward off unbearable levels of irrational anxiety through the need for, and the mechanisms of, personification. To personify is to represent things or abstractions as having a personal nature, embodied in personal qualities. Although the word personification implies a human face or figure, the investment of natural and human-made objects and animals with certain qualities of soul or spirit, i.e., animism, are manifestations of the same process.

The hypothesis explores the idea that when personification acquires duration—when it begins to exist in time—a rudimentary story begins to form. This embryonic story, an individual inkling, finds great relief in joining the established flow of existing stories and well-known myths. That is, perhaps, why children love hearing old stories over and over again.

The positive side of this personifying, a story-seeking function, is to give us the sense of belonging, of community, of recovered closeness. The negative side of the personifying process is investing others with our panic and creating chauvinism, racism, and similar manifestations.

Just like the physical body continuously works to keep body fluids moving, the temperature almost constant, the stomach acid at manageable levels, etc., so does the psychological self produce compensating, relieving images and non-verbal scenarios or proto-stories to help us deal with life's complexities. The continuous interplay of panic and recovered closeness is central in family or community life; it never goes away. Just as babies need continuous reassurance and feeding, so do adults, but in different ways. The role of festivals and public performances—rituals creating an external community commons in public places through culture-making with a strong value and practice of diversity—will redefine the experience of recovered closeness for urban dwellers in the 21st century—and potentially awaken new levels of inner connectedness.

Page No. 16

The Role of the Imaginative Function

The inner world of voluntary and involuntary imagining, the imaginative function, may be central to this re-awakening. Our human ability to nurture ourselves through sublimation and dreaming may offer a common link to the archaic layers of anxiety release through personification and enactment. The imaginative process is central to our recovered closeness. We do this nightly in dreams where, through dynamic images and an active process of personification, we self-heal and inadvertently deepen self-knowledge. This personifying function and its manifestation as rudimentary non-verbal sequences, with the potential for stories, is perhaps a starting point to connect meaning, value, and primeval processes to contemporary life through enactment and art. In his recent book, Google and the Myth of Universal Knowledge: A View From Europe, Jean-Noël Jeanneney writes:

A 2005 survey of 22,000 adult Internet users…found that 62 percent ‘make no distinction whatever between advertising and other information,' and only 18 percent could tell ‘which data were paid for by companies.'ii

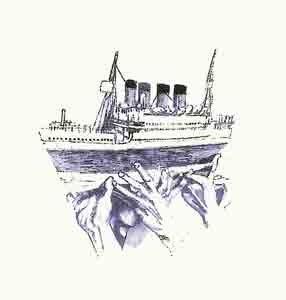

Within the continuum of oral tradition, mnemonic artifacts, through written and recorded knowledge, to virtual representations, lay both vast possibilities for numinous experiences and discoveries or, on the other hand, de-contextualized fragments and vacant information. Amadou Hampâté Bâ, in his 1960 speech at UNESCO, said: ‘In Africa, when an old man dies, it's a library burning.'iii

The question here is that, in an atmosphere of intense commodification and expanding economies, what are the mechanisms of nurturing the inner self? Parallel to the outer warnings of catastrophes and global dangers, there is also a not-so-acknowledged ecology of mind, internal self, and internalized social interconnectedness that is also threatened.

Are there—within the hidden depths of the molecular, cellular, and imaginative self in each one of us—the echoes of primordial myths and ways of knowing that represent sustainable and autonomous humans capable of living sapient qualities to the depth of their potential? Can these unborn stories, ancient myths, and living cultural matrixes contribute to that inner health and self-knowledge?

Page No. 17

Images of incubating element from the performance Same River Twice that became its emblems, July and September 2004 at ODC Theater in San Francisco, USA and at SKC Theater in Belgrade, Republic of Serbia.

- i Wikipedia, Version 1.2, November 2002, Boston: Free Software Foundation. Found online at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amniotic_fluid accessed March 20, 2009.

- ii J Jeanneney, Google and the Myth of Universal Knowledge: A View From Europe. University of Chicago Press, November 2006, p. 32.

- iii A H Bâ, ‘La Parole Africaine dans des Instances Internationales'. Records of the General Conference, UNESCO, Eleventh Session, Paris, 1960.